BK-16 Prison Diaries | The ‘ordinary’ in extraordinary times: A captive’s life in Covid-19

To mark six years of the arbitrary arrests and imprisonment of political dissidents in the Bhima Koregaon case, The Polis Project is publishing a series of writings by the BK-16, and their families, friends and partners. (Read the introduction to the series here.) By describing various aspects of the past six years, the series offers a glimpse into the BK-16’s lives inside prison, as well as the struggles of their loved ones outside. Each piece in the series is complemented by Arun Ferreira’s striking and evocative artwork.

My journey as a captive began in extraordinary circumstances. The Covid-19 pandemic had afflicted the world and, in India, a countrywide lockdown was imposed on March 24, 2020. Travel by rail, road or air was suspended. A climate of fear and uncertainty prevailed. However, the Supreme Court had asked Anand Teltumbde and me to surrender before the National Investigation Agency (NIA) by April 14—incidentally, Dr B.R. Ambedkar’s birth anniversary. Anand presented himself before the NIA in Mumbai, while I, a resident of Delhi, surrendered myself at the NIA headquarters in New Delhi.

The NIA HQ looked forlorn and stood in eerie silence. I was the sole occupant in the lock-up for 11 days. There were armed guards to watch over me and a cook summoned to provide meals as the canteen was shut. I was taken to the Safdarjung Hospital for medical check-ups every other day, covered in a plastic overall from head to toe. Other than a court visit, I remained ensconced.

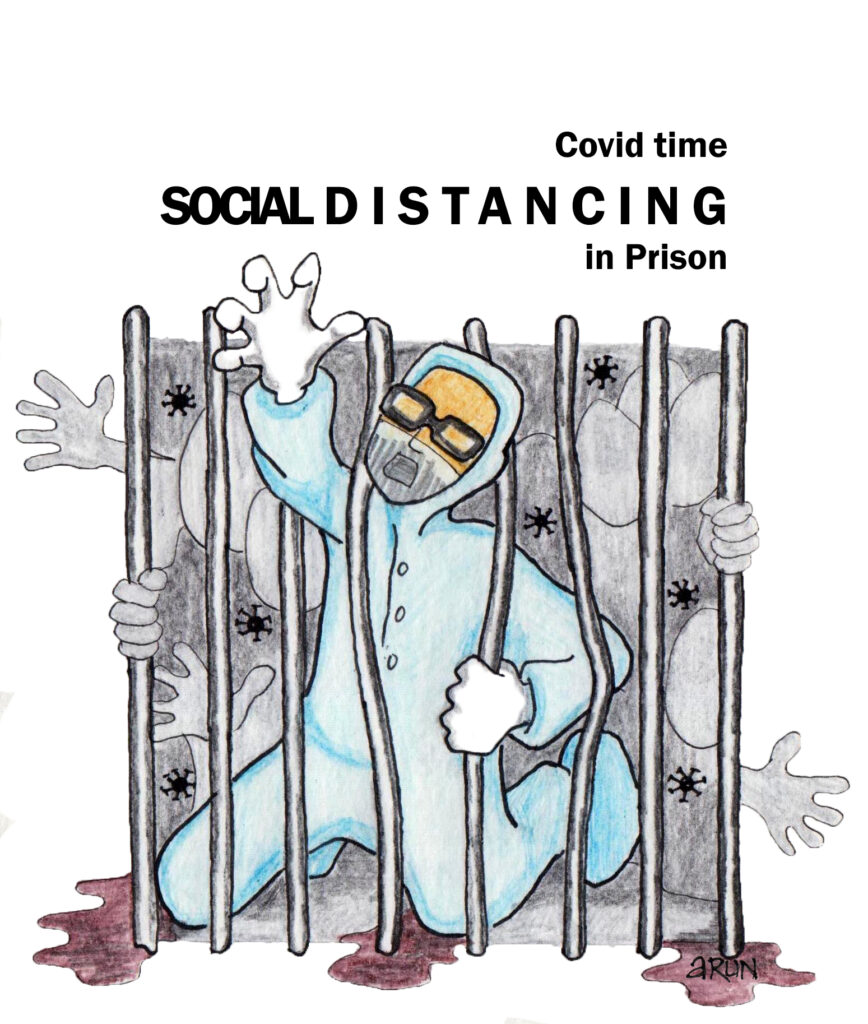

On April 25, I was taken to the court where I got to know from the deputy Investigating Officer (IO) that the NIA did not need my custody anymore and I was going to be sent to Tihar Jail. I pleaded before the court to allow me to remain where I was, in view of the pandemic, till such time when it was possible to move me to Mumbai. I pleaded that, given the extraordinary conditions, overcrowded jails went against the need to maintain “social distancing”. I submitted a written request, which the Sessions Court Judge declined.

Afterwards, I was taken to Tihar’s Jail No. 2, meant for convicts and housing the jail factory. There were 40-odd persons screened along with me and sent to Ward No. 4, which had been converted into a “quarantine centre”. There were two rows of 20 cells flanking a 10-foot-wide patch of green with trees. Each cell was crammed with four to six people. In my cell, we were four people sharing a space, roughly 15 by 7 feet, with an open toilet and bathing place. There was no question of privacy, and social distancing was impossible. There was no window and the exhaust fans did not work; one had to make do with a single fan in the sweltering heat. All we saw of the world outside was what was within our sight from behind the grilled door.

Lights were kept on through the hot and sultry night. The smell from the latrine hung in the air. My cellmates included a person who, along with his wife, had allegedly killed his parents over a property dispute. His wife killed herself in Jail No. 16, the first night we were there. Another person was an addict, and the fourth person was accused of robbery. For the first five days, we were not allowed outside our cells, except if the guards felt that a prisoner needed medical attention. Some of us requested the superintendent of Jail No. 2 to allow us out for at least some time every day. Thereafter, we were let out for half an hour to walk and stretch.

After ten days, we were moved to an adjoining ward and forty of us were kept in a barrack, locked up, with just a single toilet and a spot for bathing. This lasted for three days. Then we were shifted to different jails in Tihar. Two others and I were sent to Jail No. 3. We were kept in “isolation” for five days and three of us shared a cell. One of my cellmates was charged with abetment to suicide of his pregnant wife, and the other person was in for robbery. The munshi (prison assistant) of my ward was a life convict who allowed me to come out of the cell every evening for about an hour. I was eventually shifted to a barrack in Ward No. 9 of Jail No. 3. I was kept there for a week and finally shifted to Ward No. 4—a senior citizens’ ward.

After being pushed around for nearly a month, I finally had a “room” all to myself with a toilet and a bathing place. I had access to a library, a hospital, and a garden where I could walk, sit, and read. My quarantine and isolation had been tough but now it was behind me. Little did I know that my reverie was soon going to be broken.

An empty train to Mumbai

On May 25, late in the afternoon, my ward’s munshi broke my siesta. I had been summoned—in “ten minutes”—by the superintendent. On being asked the reason, all he said was the NIA had come to take me. I quickly gathered my few belongings and bid goodbye to my neighbours. An e-rickshaw was called and I was taken to the deputy superintendent’s office, where the NIA officers were waiting. I requested to be allowed to inform my lawyer and Sahba, my life partner. But they refused, and I was whisked away in a vehicle to the New Delhi railway station.

The station was almost empty. A special train was to take me to Mumbai. When I asked if other passengers were travelling, the two Delhi Police constables told me that as far as they knew, there weren’t any. I enquired about the pantry; they said there was one, but with no one to run it. The two constables were upset that they had been ordered by their seniors to be my escorts but were not allowed to go home and pack their clothes or food for the journey. So, the two constables and I managed on tea, biscuits and a packet of noodles each.

We reached the Mumbai Central station by 8.45 am, and the platform was crowded with armed police personnel standing in two rows. I was marched to a medical practitioner who checked my temperature, blood pressure and oxygen and taken to the NIA office at Peddar Road. I had my first and only meal of the day at the office and then rushed to the NIA Court. At 4.30 pm, I was driven to Taloja Central Jail.

I hoped at Taloja, finally, I would get to meet my fellow accused, who were, by and large, strangers to me back then. But that was not to be. By the time we reached Taloja, it was close to 6 pm. The NIA officers went inside to complete the formalities. After an hour or so, they came out fuming and angry because the jail authorities had refused to allow me inside without a Covid-19 NOC (certificate of no objection) from a medical authority. I was taken ten kilometres away to Kharghar, where a quarantine centre for prisoners had been set up at Gokhale Education Society High School. This was where I would end up spending the most horrific period of my captivity.

People outside may not fully understand the suffering prisoners endured under the guise of quarantine and social distancing during the pandemic. It’s true that prison authorities were grappling with a pandemic about which they knew little. Also, the advisory to practise social distancing was impossible in prisons because they were already overcrowded. Each day brought in new prisoners, mostly those accused of petty theft or even violation of pandemic-related prohibitions. On paper, the jail administration had set up quarantine centres, isolation wards and temporary jails to keep new prisoners for a stipulated 14 days before they sent them to regular jails. But this was not the case on the ground. While I was lucky to escape this hell after 27 days, many others were less fortunate and remained inside for up to three months.

A quarantine for prisoners

The conditions at the school were appalling. The overcrowding was severe, with 35 to 40 inmates crammed into each classroom, sleeping cheek by jowl. The idea of quarantine or social distancing turned into a bitter joke, and the risk of contracting the virus was real. Ironically, we were not allowed newspapers because multiple hands touching them, we were told, could spread the infection.

The worst part, however, was the severe lack of basic facilities. The quarantine centre was a school, of course, meant for children and designed for their use. For the 384 adult prisoners lodged, there were only three toilets, seven urinals, and a common area for bathing, offering no privacy whatsoever. Water scarcity was so acute that fellow inmates often shared their drinking water with others for toilet needs. To avoid the long queues and the pressure of others banging on the door of the latrine, I decided to wake up at 3:00 am each day to use the toilet in peace. But many of us suffered from constipation and other stomach ailments as a result. Those who were already ailing or in poor health suffered the most. I lost two kilograms in those 27 days and developed swelling in my feet. The jail doctor, who visited us once in a while, prescribed iron tablets, which made my condition worse.

The school had a playground, but we were not allowed to use it. We were confined to the classrooms-turned-barracks, and even peeking out the door could invite verbal abuse or beatings from the jail staff. Upon my arrival, I witnessed prisoners being called one by one, ordered to strip, and subjected to beatings while their belongings were searched. When it was my turn, I refused to strip. To my surprise, they complied and directed me to Classroom No. 12.

Every classroom was crowded. In fact, there was no space between my dhurrie (cotton mat) and that of the inmate next to me. Over the four weeks I spent at the school, more prisoners arrived, and we were continuously ordered to make space for them. With no access to newspapers, books, or even indoor games, we were left with nothing to do. We weren’t allowed to make phone calls to our families either. Seven days into my stay, a high-ranking officer visited the school, and we pleaded with him to allow us to call home. It took another few days for a deputy superintendent from Taloja to visit us, and after we pressed him, he agreed to provide us with indoor games, books, and phone access. However, he denied our request to use more toilets and bathing areas in the school.

Our food came from the jail kitchen, brought twice a day. Breakfast and lunch arrived around 8 am, and dinner by 5 pm. Tea was initially provided once a day, in the morning. Afternoon tea began to be provided after a week or so. Every task, from fetching food from the vehicle to distributing and cleaning the utensils after use, was allotted to Bahujans, mostly, and Adivasis; these included cleaning the passage and toilets. There were days when the urinals and the latrines would get clogged with bidis and cigarettes. In the four weeks I spent there, I joined others on a couple of occasions to clean up the mess.

Exploitation in the school-turned-prison was rampant. Some jail staff found it lucrative to charge prisoners for basic necessities like access to toilets, baths, and extra sleeping space. Those who could afford it paid between Rs 5,000-15,000 for these “privileges.” The rate for meeting family members or sending messages was Rs 2,000 and Rs 500, respectively. Meanwhile, any minor infraction or arbitrary violation of rules would result in prisoners being beaten, often with visible cruelty. I witnessed several instances of this during my time in Tihar and Taloja as well.

The eight rooms meant for quarantine were of different sizes. The biggest was 15 by 15 feet, and the smallest 13 by 8 feet. The room I was kept in had 43 inmates. Twenty-seven of them were Adivasis from Palghar who were picked up as a result of media-driven hysteria over the lynching of a “sadhu.” Two others were arrested on the intervening night of April 15-16. The police had already arrested ten Adivasis within 24 hours of the lynching. But the mainstream media played up the claim that Hindus were unsafe in Maharashtra, which was then ruled by the Maha Vikas Aghadi, a non-BJP alliance led by Uddhav Thackeray.

While the media claimed a conspiracy by Naxals and Christians was afoot to attack Hindu sadhus, the government ordered mass arrests, upending the lives of nearly 50 Adivasis. Most of them worked on contract on farms or in factories, doing any odd job they could find. Few had regular jobs. Their biggest fear was how their folks back home were doing and they were worried about tilling their paddy land as the monsoon approached.

My ordeal at the school finally ended when the NIA court summoned me on June 20. During the hearing, I was permitted to call my life partner in Delhi and my lawyer, to whom I described the grim conditions prevailing at the quarantine centre. This was reported by the print and social media. Within 48 hours of that call, I was moved to Taloja Central Jail. While some of my troubles ended, the larger conditions remained unchanged and—as I’d come to know later—got even worse.

Between April 14 and June 22, I spent 44 days in quarantine and 17 days in isolation. But the experience represents just one case among many undertrials subjected to similar conditions throughout the prison system during the devastating pandemic.