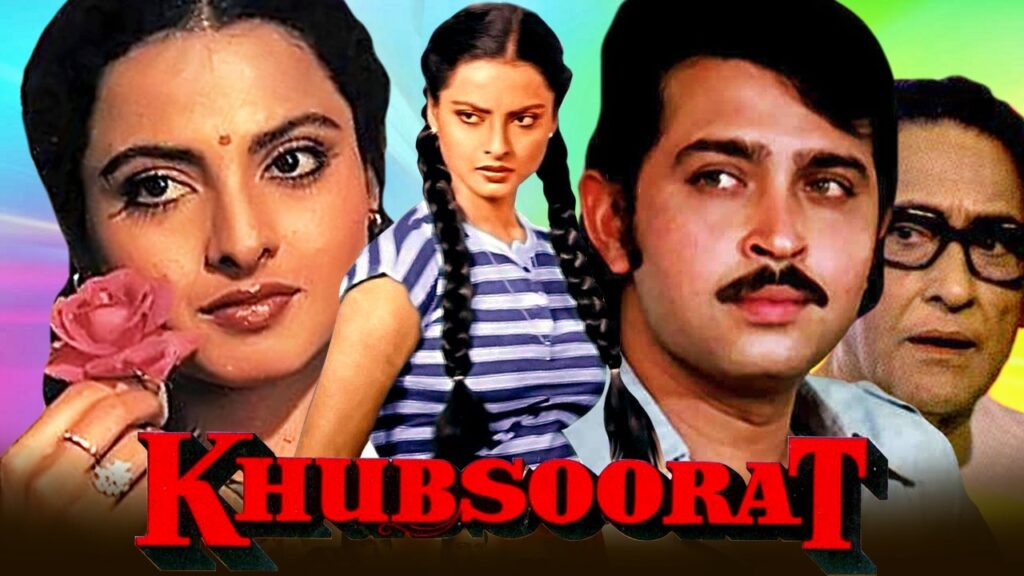

Khubsoorat was an instant classic when it came out in 1980. A box office hit that earned multiple Filmfare nominations, it secured Rekha the Best Actress award and director Hrishikesh Mukherjee the Best Film award for the year. The film was remade in Telugu as Swargam, in Tamil as Lakshmi Vandachu, and Malayalam as Vannu Kandu Keezhadakki.

It still inspires references and homages, from the 2014 romantic comedy with the same title to Karan Johar’s 2023 film Rocky Aur Rani Kii Prem Kahani, which draws heavily from it.

Khubsoorat appears to be as mainstream as they come. It is a family comedy about the wilful Manju (Rekha) going up against the strict matriarch Nirmala Gupta (Dina Pathak), and stars other big names like Ashok Kumar and Rakesh Roshan. Yet the subtext suggests something different.

Nirmala bears obvious similarities to Indira Gandhi in the way she holds complete authority and power over the family unit she runs. She maintains control over her Hindu Undivided Family (HUF), while Gandhi controlled the entire country, declaring an Emergency from 1975 to 1977. Khubsoorat released when Indian cinema faced harsh censorship, eerily similar to the state of repression today.

The goal was to portray a sanitized image of the country that fit in with the ideals being projected by the ruling party. Action sequences were limited; images of blood and liquor bottles and references to sex were removed as well.

This resulted in the repression of artists who used their work to challenge the state-protected image of India. Kishore Kumar’s music was taken off All India Radio (AIR) for refusing to promote Indira Gandhi’s 20-point programme for agricultural and industrial growth; filmmakers like Satyajit Ray and Raj Kapoor were advised to change their directing methods and switch film stock due to the government’s rationing of raw film negatives.

In this context, Khubsoorat uses the rule of the matriarch, Nirmala, to create a parodic version of India under Indira Gandhi. The family in Khubsoorat acts as a microcosm of the nation, with the mother as the head of the country, and her family serving as citizens or subjects who must always be told what to do—not only for their own good but also the larger good of the nation/family.

Nirmala maintains complete control and the rule of law within her household. Everyone from her husband, Dwarka Prasad, to the youngest granddaughter must eat breakfast at the same time, even if their personal schedules might not allow for it. Nirmala imposes her taste and thought over her family, not allowing her two oldest sons to indulge in their hobby of playing juaa or cards. She is also against her youngest son’s obsession with Western music, forcing him to listen to his record in secret when he is meant to be studying.

Khubsoorat reflects how filmmakers and writers like Gulzar use allegories, musicals, and comedies to poke fun at the establishment. His work has usually been able to fly under the radar in ways that other filmmakers couldn’t manage. His grittier contemporaries like the Salim-Javed duo, for example—who created the ‘Angry Young Man’ (Usually portrayed by a young Amitabh Bachchan)—were more brazen in criticizing the corrupt political establishment.

Their initial ending for Sholay (1975) featured the dacoit villain Gabbar being impaled to death by the former police officer Thakur, with the help of the former convicts Jai and Veeru. The actual ending was much tamer, featuring Gabbar being arrested rather than murdered, because the Emergency-era censor board was uncomfortable with the depiction of a former police officer taking the law into his own hands.

Khubsoorat is an Emergency film in disguise, one of the first films from that time that addresses the turbulent period in the country, but through humor, whimsy, and song, never actually alluding to the Prime Minister or stating their grievances with the government. The film also makes the argument for art as resistance, demonstrating the enduring importance of movies like Khubsoorat today.

Introducing the Families and Plot

Nirmala Gupta, the wife of Dwarka Gupta (Kumar), is the matriarch of a large, affluent Pune-based family. She has four sons, Sundar, Chandar, Indar, and Jagan. Sundar, the oldest, is married to Badi Bahu ( she is always referred to by the moniker of ‘eldest daughter-in-law’), and they have one daughter, Munni.

Khubsoorat begins when Chandar Gupta marries Anju Dayal, the oldest daughter of the Dayal family and Manju’s older sister. Once Anju is married and settled into the household, Manju visits her and is shocked to learn about the repressive rules that Nirmala has in place to keep her family in check. Manju’s dismay indicates that although this behavior in a traditional joint family is normalized as standard, it’s disturbing to see a parent figure exert this much control over their family.

With the help of Anju and Jagan, Manju slowly convinces the family to break Nirmala’s rules and learn to embrace the hobbies and passions that they had been keeping repressed for fear of Nirmala’s anger. She encourages Jagan to listen to his Western music records, Sundar and Chandar to play the card games they enjoy, and even encourages Bari Bahu and Dwarka Gupta to put on a musical performance using their respective skills as a dancer and tabla player. Nirmala has discouraged all these activities, treating them as silly indulgences that go against the pristine image of the family.

Jagan, Manju’s insider source on the family dynamic, explains that Nirmala’s rules are not just for her benefit, but are meant to help the family stay together and remain happy and successful. The family, or the obedient citizens, cannot fathom a life that lies outside the control of the matriarch. ant.

We meet the Guptas at breakfast, where it’s implied that the family members will meet strict consequences if they don’t arrive on time; this rule is even extended to Munni, a child. The Dayals (Anju, their father, and their cook) are also introduced at breakfast, and the contrast couldn’t be clearer. The daughters joke around with their father and cook while making rhyming couplets, often political jokes, or humor at the expense of one of the family members.

The absence of the mother is later established as one of the reasons why the father feels the need to joke around and behave childishly with the daughters. Either way, Khubsoorat makes it clear that the presence or absence of a matriarch affects the way the family behaves with each other. Khubsoorat features a subversion of traditional gender roles in different ways with both families.

In the case of the Dayals, the father has taken on a more nurturing, caring role in the absence of the mother, while with the Guptas, the mother is a stronger, more patriarchal figure despite the presence of the father. Even then, he occupies the space of the head of the family, implying that despite the apparent subversion, the patriarchy is still being upheld, even with the Guptas’ less stereotypical arrangement.

Nirmala Gupta as Indira Gandhi

Nirmala Gupta is not a clear-cut copy of Indira Gandhi. Her house is run the way the country was during the emergency period: she dictates what her family will eat, when they will eat it, who they go out with, where they work, and how they spend their free time. Gandhi, similarly, decided what was imported into the country, what media people had access to, and what jobs people were ultimately allowed to do. She also exerted control over people in violent ways, by cracking down on trade unions and enacting forced sterilization policies.

The comparison between the two is made clear when Manju is shocked to hear about the rules surrounding human behavior in the house. Her sister, Anju, tells her, “Khaane peene ke, hasne bolne ke alag kayde hote hain” (There are separate rules for eating, drinking, laughing, and speaking here).

Shocked, Manju responds with “Arre baap re, aise toh Emergency main bhi nahin hua, bilkul military rule lagta hain bhai” (Wow, this didn’t even happen during the Emergency, this seems like complete military rule). Somewhat hyperbolically, Manju points out that the characters’ lives at home are just as bad, if not worse, as the state of the nation between 1975 and 1977. Anju brushes her sister’s comment aside and implores her to get along with the matriarch for everyone’s good.

This is not the first time politics has been brought up in a joking manner. When we are introduced to Manju and her family, the group is engaged in a friendly Shayari competition, making jokes and spouting rhyming one-liners to each other’s amusement. The jokes turn political when they mention Yashwant Rao Chauhan, one of the members of the new Congress Urs party. Anju and Manju’s father says, “unhone Indiraji ko chhod diya” (He left Indiraji) to which Anju responds, “Sab Ne Milke Congress ko tod diya” (Everyone broke the Congress together). The bit ends with the father saying “sawaal hain ekta ka” (The question is of unity), referencing Indira Gandhi’s rhetoric at the time.

All the comparisons are hyperbolic and humorous. At one point, Nirmala says, “Prime Minister ko apna kaam karne do” (Let the Prime Minister do her job) when the family jokes that she is willing to sacrifice the health of its citizens to earn money. Nirmala supports the autocratic regime while being blind to the similarities between the nation and her household.

Yet there is always plausible deniability about the parallels, unlike with Aandhi (1975), a Gulzar project about an ambitious female politician that was banned by the Indira Gandhi-led government, where the aesthetics and promotional material doubled down on the similarities. Khubsoorat does not postulate a specific explanation as to why authoritarianism or fascism is bad; it simply encourages the characters to follow their heart’s desires, as that in itself is enough to go against the fascist ideology that rules the household.

Squashing Individual Interests for the Collective Good

Dwarka Gupta is obsessed with flowers and gardening. It’s no coincidence that the first transgression of the film occurs when Dwarka walks into the house without wiping his slippers after gardening. He is so lost in the bliss he feels when he steps out into the garden (as seen in the title sequence) that he forgets about the basic rules of the household.

We repeatedly see this theme of bliss as a route to transgression through Manju’s invocation of ‘nirmal anand’—pure bliss as the very aim for rule-breaking. This explanation always works, though, as she convinces the family to start pursuing hobbies that help them find joy in their lives.

Meanwhile, Nirmala Gupta (with a name ironically close to ‘nirmal anand’) believes that true happiness lies in the good of the collective family unit rather than the growth of the individual. Dwarka’s gardening doesn’t serve a larger purpose for the family, and therefore, his interest in it should be considered unimportant. Manju brings the family together through their individual interests, but Nirmala’s rules only keep them apart.

Another reference to Indira Gandhi’s policies—like granting herself extraordinary powers during the emergency and using them to crack down on dissenters, protesters, and ‘anti-government’ groups—which were ostensibly meant to aid in the growth of the citizens, but just did the opposite.

“Kaante ke bina gulab kya honga, aur gulab honga toh kaante bhi honge, aur woh chubenge bhi aur chuban jhelna bhi padengi,” (What is a rose without thorns, if there is a rose there will be thorns, and they’ll prick you, but you’ll have to tolerate it) Nirmala says to her husband when he attempts to show her a thornless rose. Nirmala postulates a reasonable explanation for her rules: there can be no pleasure without pain. In fact, to her, pleasure seems to exist within the nexus of pain. She cannot imagine a world where there are roses without thorns, as the presence of the thorns renders the rose beautiful.

It’s no coincidence that they chose the motif of the rose. It was favored by Jawaharlal Nehru, Indira Gandhi’s father, who often wore a cut rose in the lapel of his waistcoat. We see this outfit on Rekha when she plays the ‘Inquilaabi poet’ (revolutionary poet) in the anti-authoritarian skit that she, Anju, Munni, and Bari bahu perform for the men later in the film.

The skit follows a despotic King who wants his citizens to behave perfectly. He arrests people for sneezing and for doing “odd” things, such as being awake at night and not having the “correct” emotional reaction to situations. Manju’s character in the play is a revolutionary poet who uses his art to go against this despotic ruler. This king is a reference to both Gandhi and Nirmala, someone who pretends to care for their citizens but ultimately just wants to exert control over them.

Songs and the Spirit of Rebellion

Once she has reached her breaking point with Nirmala’s rules, Manju decides she must take some kind of action against the tyranny of the household. She identifies Jagan, the youngest son, as an easy target to participate in her rule-breaking. She sings Kayda Kayda to get Jagan to help her with her plan to change the politics of the household. As the youngest and the one who has already displayed an interest in art through his record collection, he is the most susceptible to her ideas about how the household could be run.

Before the song begins, she explains they should break rules for ‘nirmal anand’ or the pure joy they will feel when they finally live according to their own rules. The song is an attempt to imagine a radically different world that does not follow the rules of the authoritarian society in which they live.

Kayda Kayda exists in a topsy-turvy fantasy world. They sing about a world where everything can be anything; the sun can be blue, the birds can be in the ocean, and the fish can fly through the sky. She starts the song by saying, “Kaayda todke socho ek din Chaand nikalta neeche se aur maidan pe rakha hota” (Imagine one day when we break all the rules, the moon will come out from below and stay in a field).

The song presents rule-breaking as completely fantastical. Everything that could be considered transgressive is done through the guise of a magical realism-esque dream sequence. Children are employed to soften the message of the song and render Manju’s intentions child-like and simplistic.

Although Manju is engaging in a radical and dangerous act by allowing herself to imagine a new world, she is still treated as ultimately harmless. Her motivations are without malice and come from a childishly altruistic place; therefore, she cannot be suspected of wanting to break apart the household, or at a larger level, the nation. Khubsoorat uses whimsy and imagination to hide its larger message of wanting the nation to be radically different.

Here, Manju is almost a stand-in for the filmmakers. Just like them, she can conjure up entire realities based on her ideas and imagination. She can bring the extraordinary into existence. The framing of the song helps shape the narrative that the artists themselves are not attempting to cause any mischief. The song helps them pass off Khubsoorat as just a fun and fantastical film, devoid of significant meaning.After this song, the family’s rule-breaking begins in earnest. She convinces Bari Bahu to practice Kathak again and gets Dwarka Gupta to accompany her on the tabla. She even gets the two older brothers to stop playing bridge at the office in secret and instead come home and play with Anju and Manju, who both enjoy the game.

Manju is helping to bring the family together. By uniting their individual hobbies into a form of collective action, she is mobilizing the nation. She suggests that the only way the individual family members will ever be able to change their way of living is by working together. The filmmakers thus suggest the only way out of fascism is through collective action.

This is especially relevant now when the ruling party is invested in turning the country into a singular, undivided nation, one that doesn’t allow for plurality of thought and opinion. Khubsoorat posits that the only way to ever beat this singularity is to come together despite smaller differences.

The song ‘Sare Niyam Tod Do’ (Break all the Rules), in the style of a Nukkad Naatak or political play, is performed in male drag by all the women in the family, including the granddaughter, and excluding Nirmala. They perform the song to the audience of male family members, attempting to use it as a playful means of helping them subvert the system and stand up to Nirmala.

The play features a despotic king who imposes arbitrary rules on his subjects. The king is overthrown by Manju in the guise of a poet who explains that there is nothing wrong with doing the things that bring you joy. She sings, “Sare niyam tod do” (Break all the rules) and “Inquilab Zindabad” (Long Live the Revolution).

Although they are aligning themselves against tyrants and despots, they don’t even use Nirmala as an example of a tyrant. They created a play within the play to make their point without actually implicating the female tyrant, whom this film is about. In a way, this is almost Shakespearean.

The separation acts as further insulation against censorship while still making the role of art and the artist within a despotic political system incredibly clear.

Art as the Solution to Authoritarianism

Khubsoorat postulates that art—or rather creating art in the pursuit of joy and pleasure—is the solution to authoritarianism. Through Manju, the film declares that joy and art are interrelated; there can be no society without art, simply for the pursuit of pleasure.

Later, after Nirmala sees the skit staged by Manju and the other women, she is hurt—not because of the activities themselves but because of the character’s desire to do the activities behind her back. She is hurt because of her family’s lack of trust in her. The other characters are immediately humbled, especially the impetuous Manju. They begin to see that their actions are selfish and ultimately hurting the unity of the family and nation, just as Nirmala Gupta wanted.

She is hurt that no one trusts her, and yet throughout the movie has made it clear that she would never approve of the kind of “frivolous” fun and activities her family members want to engage in. She has a clear vision of how a family should behave and cannot entertain a version of reality that goes against her desires.

When Inder, the third son, reveals he is in love with Manju and wants to marry her, Nirmala dismisses the idea because she believes that Manju doesn’t care for anyone other than herself. She is proven wrong when Manju dedicates herself to caring for Dwarka, despite her own desire to leave and return home.

Manju has always cared for the family. She goes out of her way to understand each family member’s hobby and helps them figure out creative ways to pursue them, despite the draconian laws they live under in the household. But this form of care is foreign to Nirmala.

When Nirmala finally softens towards Manju, she says, “Iss Ladki ne toh mujhe hara diya” (This girl has beaten me), implying that despite her misgivings, Manju has finally managed to carve out a place for herself within Nirmala’s heart. Manju never changes throughout the movie, it is only Nirmala’s perception of her that changes.

Khubsoorat tells the audience to pursue freedom at all costs while simultaneously showing Manju, the prime instigator, submitting to the role of dutiful bahu. It implies that artists can pursue freedom and joy within the constraints of the larger society. Authoritarianism cannot be defeated in a day, but as long as resistance remains, it can be slowly whittled away at. Manju appears to be capitulating to authority (by taking on the role of a bahu), but ultimately never bows to the pressure of fundamentally changing who she is.

Looking back at this film 50 years after the declaration of the Emergency, we are once again living through extreme censorship as a result of a fascist government that is attempting to create the false idea of a singular India, one that doesn’t contain dissent, protest, or ‘anti-government’ elements. Khubsoorat offers us a solution when facing draconian policies: play. It suggests that as long as the spirit is willing and able to create art, nothing is impossible.

As Manju says in Sare Niyam Tod Do, Inquilab Zindabad. Say it and it will be true.