On the early morning of March 9, 2025, Jelani Cobb was on his way to John F. Kennedy Airport, about to board a plane to the United Kingdom, when he learned that Mahmoud Khalil had been arrested.

Khalil—a recent graduate of Columbia University, a Palestinian advocate, and a green card holder—had been approached by Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents the night before, in the lobby of his apartment building. He and his wife, who was eight months pregnant, had just returned from an Iftar dinner when three ICE agents entered their Columbia-owned building without a warrant and arrested Khalil without offering any explanation.

Cobb, for a moment, considered staying in New York. As dean of Columbia Journalism School, he questioned whether he could leave while his university was at the center of such a crisis. It wasn’t just Khalil’s detention: the day before, the Trump administration had announced the cancellation of $400 million in federal funding to Columbia, part of a broader campaign against American universities, which had become the epicenter of the protests against the genocide in Gaza and the United States’ role in it. Still, he boarded the plane to Oxford, where he was scheduled to give the memorial lecture at the Reuters Institute.

Cobb had stayed up late preparing a talk on the public’s eroding trust in the media. But by the time he took the stage, he had rewritten parts of it. It became, as he put it, a “developing speech.” He mentioned Khalil’s arrest, Trump’s announcement, and reflected on a recent conversation about the legacy of the McCarthy era.

“Our universities, our governments, certainly our news organizations were meant to not only embody particular principles but to assure that they can be preserved and transmitted across generations,” he told the audience. “The paradox, of course, is that the minute you establish something based upon principle, you are confronted by the question of when you will bend for expediency.”

Cobb had planned to stay in the UK for a week. Instead, he gave the lecture and flew right back, sending texts with his colleagues and trying to follow emergency meetings on his phone as he traveled. He needed to be with his students.

***

When Cobb was appointed dean of one of the most prestigious journalism schools in the country three years ago, he couldn’t have predicted the storm of challenges that lay ahead. He was at home with his five-year-old daughter when he received the call from Lee Bollinger, then president of Columbia, offering him the job. Cobb, still on the phone, explained the news to his daughter, who ran to her room and returned with a bunch of stickers—something she’d learned in school was given when you do something good.

“You can pick whatever sticker you want,” she said. He picked a sticker of a pig and placed it on his phone, he recalled in an interview with Columbia Journalism Review.

It was 2022. The consequences of the pandemic lingered, public trust in the media—undermined by increasing political polarization and the rise of misinformation—had eroded, the future of the industry was uncertain, and tuition costs continued to rise. And while those challenges remained, by Cobb’s second year as dean, the ground had shifted.

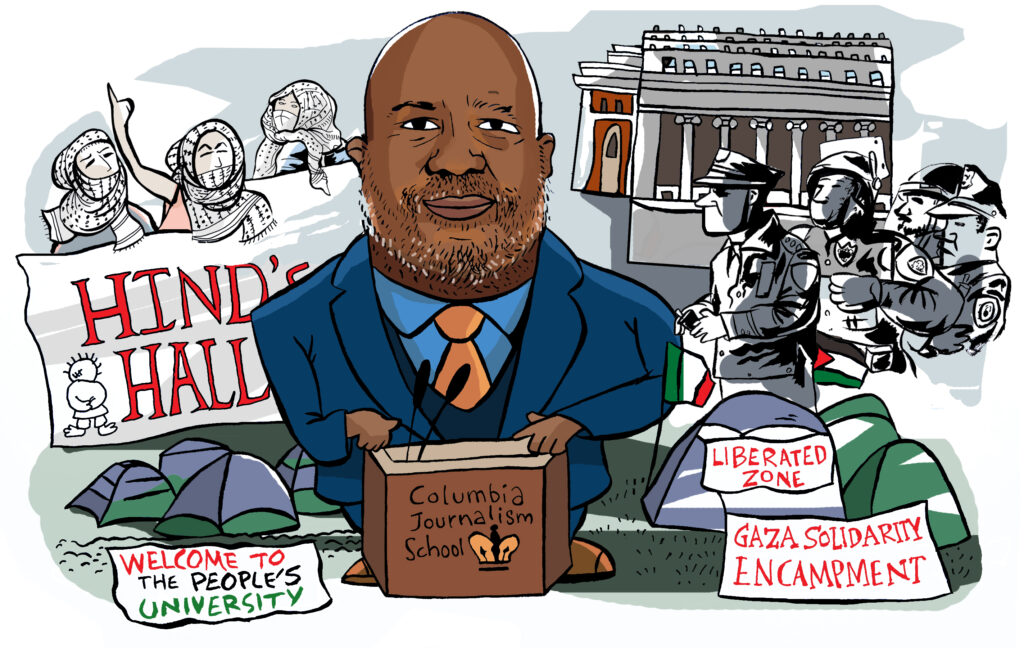

In the fall of 2023, Israel escalated its assault on Gaza, sparking what many human rights organizations and international observers began describing as a genocide. At Columbia, an encampment was set up just outside the doors of the journalism school, calling for the university to divest from companies that “profit from Israeli apartheid, genocide and occupation in Palestine”.

One year later, the Trump administration began attacking higher education, undermining free speech, chilling academic freedom, and threatening funding by arguing that the university wasn’t acting to prevent “chaos and antisemitic harassment” on and near its campus. And standing in front of the Columbia Journalism School—one of the institutions now in the spotlight—is its first Black dean: a writer and historian who has dedicated most of his career to the study of Black History and the coverage of civil rights.

One of his colleagues, Columbia professor and journalist Robe Imbriano, put it plainly: “Everyone is looking at him.”

***

Jelani Cobb grew up in Queens, one of the most diverse counties in the United States, in the 1970s. When he was eight years old, his mother took him to the neighborhood public library so he could ask for his first library card. “Everything that I’ve been able to do has flowed from that moment,” he said when the library honored him in 2022.

Cobb’s family didn’t go to college, and when he was admitted to Howard University to study English in the late 1980s, he carried a fear of not fully belonging. He spent seven years completing his undergraduate, often pausing his studies when he couldn’t afford tuition. At the time, professors had been progressively integrating African American literature into the curriculum—a shift that gained traction in the 1970s following the civil rights movement.

Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, who taught Cobb American literature, remembered it as an especially exciting time to be at Howard. “There was all sorts of literature being taught that hadn’t been taught twenty years before,” she told me.

A little older than the rest of the cohort, she soon recognized that Cobb was one of her best students—not only a strong writer, but also an eloquent speaker who stood out in class discussions. From the start, his profound interest in Black history came through in his essays.

“He was able to use his voice in our endeavors, and he was able to use his writing,” Garland-Thomson recalled. “When you put those two things together, those are skills that are really important for becoming a scholar, a leader in higher education, and a journalist.” She and Cobb spent time discussing his next steps. She wrote his letters of recommendation, and ultimately, he decided to pursue a PhD in American History at Rutgers.

His mother was in the audience the day he received his doctorate in 2003. She watched as her son—a tall man—stood up from the middle row. “I hope he doesn’t have to go to the bathroom,” she thought. But then he passed his diploma to the woman sitting behind him, who passed it to the person behind her, until it reached his mother’s hands.

“That was one of the most important moments of my life,” she recalled years later in an interview with Cobb for StoryCorps, “I was ten feet tall.”

***

In April 2024, when students at Columbia launched an encampment in solidarity with Gaza, Jelani Cobb found himself remembering his own days as a student activist. As an undergraduate at Howard University, he had helped organize a protest against the appointment of Lee Atwater, a Republican known for his racist campaigns, to the university’s Board of Trustees. Cobb and his colleagues occupied the administration building, locking themselves in for several days.

The protest worked: Atwater resigned, and the university accepted their demands, which included promoting a more Afro-centric curriculum, streamlining financial aid, and improving student living conditions.

At Columbia, the primary goal of the protests was to pressure the university to divest from Israel. In December 2023, Columbia University Apartheid Divest (CUAD)—the coalition of student organizations leading the movement—submitted a proposal to the university’s Advisory Committee, urging divestment from a list of companies including BlackRock, Airbnb, Amazon, and Alphabet. CUAD argued that by maintaining financial ties with these companies, Columbia was directly or indirectly profiting from Israel’s actions in Palestine.

Some of the companies, the proposal noted, do business with the Israeli government—by supplying weapons or developing surveillance technology—while others, like Airbnb, profit from the occupation by listing properties in illegal settlements. “By failing to divest from companies profiting from Israeli apartheid, Columbia is complicit in genocide,” the proposal stated.

In the early hours of April 17, students pitched tents on one of the campus lawns, declaring it a “liberation zone” and hanging a banner that read “Gaza Solidarity Encampment”. The following day, University President Nemat “Minouche” Shafik—the first Middle Eastern and the first woman to hold the position—announced the suspension of the students involved and called in the NYPD. “I took this extraordinary step because these are extraordinary circumstances,” she wrote in an email.

Jelani Cobb advised her not to. “Don’t call the NYPD,” he told her. But she did it anyway.

That afternoon, officers in riot gear dismantled the encampment and arrested more than a hundred protesters, zip-tying their hands and escorting them off campus as students and faculty looked on in disbelief. Cobb was among the onlookers, taking photos of a scene that hadn’t been witnessed on campus since the 1968 protests against the Vietnam War.

The university may have hoped to end the protest through repression, but the arrests only galvanized students. That same day, they jumped the fences of an adjacent lawn and established a second encampment, raising their banners again. This time, it lasted eleven days.

Protesters turned the space into a well-organized, self-sufficient community. They provided hot meals and supplies—everything from board games to portable chargers—and held not only protests but also teach-ins, yoga sessions, and film screenings. High-profile figures, including Gaza-based journalist Motaz Azaiza, activist Indya Moore, and writer Norman G. Finkelstein, came to speak in solidarity.

President Shafik sent periodic emails to the university community about the ongoing situation. “I know that many of our Jewish students, and other students as well, have found the atmosphere intolerable in recent weeks,” she wrote. “The encampment has created an unwelcoming environment for many Jewish students and faculty.” (The protesters, some of them Jewish themselves, publicly denied that antisemitism was present in the encampment.)

Messages from the administration often emphasized concerns about antisemitism, sometimes mentioning Palestinian suffering only in passing or as a secondary point. On December 2023, even before the encampment, as protests were taking place weekly, Columbia’s deans, including Cobb, issued a joint statement acknowledging that phrases such as “by any means necessary,” “from the river to the sea,” and calls for an “intifada” were experienced by many Jewish, Israeli, and other members of the community as “antisemitic and deeply hurtful”.

At the same time, the statement also acknowledged that many others felt silenced by fears of being labeled antisemitic or supportive of terrorism simply for expressing grief over Palestinian lives lost in Gaza or the West Bank.

Rashid Khalidi, a Palestinian-American historian and longtime Columbia professor, responded in an open letter published in Mondoweiss. “This statement amounts to a new norm that prohibits using or learning about these terms and their histories, in favor of the privileging of a politics of feeling,” he wrote. “While perhaps appropriate to a kindergarten, it is hard to imagine an approach more contrary to the most basic idea of a university.”

Jude Taha, a Palestinian journalist, chose to attend Columbia Journalism School in 2023 specifically because Jelani Cobb was dean. She admired his reporting on the Black community, which she saw as having deep parallels with her own work on Palestine. What stood out to her was his approach: always grounding the present in its historical context. Her relationship with Cobb deepened after October 7, 2023, when they began having what she describes as “honest and open” conversations.

Taha shared her thoughts on how the school—and Cobb himself—was responding to the crisis and what kind of support she felt was needed. She felt comfortable disagreeing with him—and safe voicing her concerns. As the daughter of Palestinian refugees, with family in the West Bank and friends and colleagues in Gaza, Taha often felt powerless.

On December 6 that year, after learning that Refaat Alareer—a beloved Palestinian writer and professor from Gaza—had been killed in an Israeli air strike in Gaza, she broke down on her way to campus. But when she arrived, she found students discussing homework, as if nothing had happened. She felt like she was living in two separate realities.

***

In 2014, Jelani Cobb, in a piece for The New Yorker about the shooting of a Black eighteen-year-old in Ferguson, wrote: “I was once a linebacker-sized eighteen-year-old, too. What I knew then, what black people have been required to know, is that there are few things more dangerous than the perception that one is a danger.”

As a staff writer at The New Yorker, Cobb has written extensively about the killings of Black innocents by the police—George Floyd, Eric Garner, Renisha McBride, and Trayvon Martin—to name only a few. Always a similar story, unfolding in a different place, under familiar circumstances. He has carried those names into his reporting and the anger they stirred in their communities.

On Columbia’s campus, during the protests, another set of names and images moved students to action: Hind Rajab, a five-year-old girl killed by an Israeli attack in Gaza; Refaat Alareer; Shireen Abu Akleh, the veteran Palestinian journalist killed by an Israeli sniper while reporting in Jenin; Shaban al-Dalou, the 19-year-old who was burned alive with his mother after Israel bombed Al-Aqsa Hospital; Fatima Hassouna, a 25-year-old photojournalist killed in an Israeli airstrike along with ten members of her family; the girl in the blue shirt who recognized her mother’s body by her hair in Gaza; the father holding up the decapitated body of his child in Rafah. Protesters often spent hours reading aloud the names and ages of Palestinians killed, to honor them.

In his pieces, Cobb, a historian, always weaves history into his reporting—a quality his former professor, Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, sees as distinctive, one his peers admire, and one his students learned to embrace in his classes. Allie Pitchon, a 2020 graduate of Columbia Journalism School, attended Cobb’s Ethics class. She remembers how he taught them to examine prevailing narratives by exploring their history. “His class made us question the mainstream narratives,” she said. “He did a very good job tracking how historically certain groups of people have been treated in the media.”

Columbia’s Journalism School is one of the smallest in the university, fostering an unusual sense of intimacy among students and faculty. In the class that began in 2023, Palestinian and Israeli students shared classrooms, alongside professors who held a wide range of perspectives. Tensions were present in the everyday life of the school. When the Arab and Middle Eastern Journalists Association at Columbia, for instance, proposed installing a memorial in the lobby to honor journalists killed in the war on 9 February this year, some faculty members expressed hesitation, arguing it could be seen as the school making a political statement.

Cobb navigated those pressures, emphasizing that the memorial spoke to losses within the journalism community, and it was ultimately installed. (However, in May 2024, before commencement, a new debate emerged over whether it should be removed—prompting students to circulate a petition asking that it remain at least through the end of the academic year, so their families could see it.)

Bruce Shapiro, a professor at the school and director of the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma, reflected on how the school responded to the unfolding trauma. “There were students, there were faculty, with very strong and sometimes diametrically opposed views,” he said. “And the question became: what do we do with that as journalists?”

The four Journalism-school professors I spoke to for this piece agreed that Cobb offered a clear answer to that question: report. When he became dean, he introduced the slogan “Reporting Begins Here”—a phrase that, amid the crisis, took on renewed meaning. “It is not an overstatement to say that Jelani set the tone for how the school would respond,” said Professor Robe Imbriano. “It gave us all purpose in the middle of this.”

The attacks on Gaza—and the deaths of her friends—led Jude Taha to consider leaving the program, the school, and even the United States to return to her community in Jordan. “I felt ignored,” she shared, “like my work meant nothing, and my time there would mean nothing.” She sat down with Jelani Cobb to talk it through.

He listened carefully and offered advice. “If you’re not here to do the work you need to do, think about who will be here to do the work that you need to do,” she remembers him saying. “That really motivated me,” she reflected. She decided the best thing she could do was stay—and try to be the change she wanted to see.

The encampment abruptly changed the rhythm of life at the school. Several students, including Taha, committed themselves fully to covering the protests—skipping classes, pulling all-nighters, and even sleeping in Pulitzer Hall. A group of professors, including Shapiro and Imbriano, and others like Azmat Khan and Nina Berman, stayed close, ensuring students had the support and safety they needed as they worked. For some of them, the school, although always part of the university as a whole, felt like an island where another way of managing the situation was possible.

Nandhini Srinivasan, an international student from India, had been covering the protests from the beginning. She laments that the journalism school wasn’t as vocal as it should have been about the Palestinian journalists killed in Gaza, or about the broader assault on press freedom. “This should have been the only topic that the J-School talked about for months,” she asserted. It wasn’t. Some professors brought in Palestinian guests and made efforts to discuss the war, but others almost ignored it in class.

Still, when it came to covering the encampment, Srinivasan and other students appreciated how supportive the professors were. “I always knew that the journalism school had my back,” she said. “They were so actively involved in making us able to do our work.” Alone in New York City, she even wrote her professors’ phone numbers on her forearm in pen, in case she was arrested by the NYPD while reporting.

From the first day of the encampment, Columbia’s administration restricted access to campus to university ID holders—a radical shift, considering the campus includes a street that had long been open to the public. The decision also barred journalists from entering, limiting their ability to report on students’ demands.

The move quickly drew criticism. Reporters pointed out the irony of Columbia—home to the Pulitzer Prizes—banning the press from its grounds just as a major national story was unfolding on campus. In response, Cobb authorized a statement from the Columbia Journalism School’s official account: “Columbia Journalism School is committed to a free press. If you are a credentialed member of the media and have been denied access to campus, please send us a DM.”

Cobb himself, along with students and professors, started running to the gates and escorting reporters onto campus. The move, in some ways, defied the administration’s decision. “I explained to the administration why we did it, and also that, however irritated people might have been by the fact that we did it, it would have been much, much worse for us if we had not,” Cobb told me.

Days later, the university administration went further, limiting access to campus to everyone except those who lived in the dorms. Cobb, once again, pushed back so his students could enter and continue reporting. “It was a period of intense demand and pressure on him,” recalled Shapiro. “But he never let it show. He projected a calm sense of mission in that moment.” Shapiro said he has never felt better about a dean than he did then.

Other professors agree. Alexander Stille, director of the Master of Arts program at the school, described Cobb as a “voice of good sense and moderation” and a key liaison between the journalism school and the wider university. “Jelani was very active,” Stille said, “and I think was a very respected voice in a very difficult, complicated period.”

One night, while covering the encampment with a group of students, Srinivasan and Taha realized that Pulitzer Hall had been locked, trapping their equipment and personal belongings inside. It was around midnight, but Taha decided to call her dean. Cobb picked up. “I’ll be there in a bit,” she remembered him saying before hanging up. Shortly after, he arrived at the school and let them in. “I don’t think he knows how much that meant to me,” Taha said.

***

Cobb was wearing multiple hats during those weeks. He wasn’t just the dean of the Journalism School—he was also one of four faculty members involved in negotiations with the student protesters, including Mahmoud Khalil. Having spent years documenting the impact of police brutality on communities, Cobb was determined to help bring the encampment to a peaceful end and avoid another NYPD intervention.

To do that, he tried to see the situation through the students’ eyes, asking himself how he would have approached it back when he was a student activist. “I tried to make sure I was always respecting the intelligence of the students and the decisions they made,” he said.

On April 29, the students, realizing the university was not going to meet their demands, decided to occupy Hamilton Hall and renamed it Hind’s Hall. “We’ll honor all the martyrs,” a protester chanted from the building’s balcony. Negotiations continued the following day, but no agreement was reached, and the university ultimately decided to call in the NYPD once again.

“We were not successful,” Cobb said, reflecting on that moment.

Jelani Cobb returned to Pulitzer Hall—not only as a dean, but as a journalist. Shapiro remembered seeing him on campus with a camera and a notepad in hand, slipping back into the instincts of the reporter he had always been. “I read in him a kind of relief,” Shapiro said. “The relief was not that the negotiations were over, it was ‘now I can do my job.’” By then, the students had created a pop-up newsroom on the first floor of the school, with professors regularly bringing them food and snacks so they could keep working.

As word spread that another NYPD raid was imminent, Cobb gathered the students together. He praised their work, telling them they had done an extraordinary job over the past weeks. “There’s no need to get into the middle of the fray—you’ve done enough,” he said, urging them to stay safe inside. Cobb recalled sardonically that the moment he finished speaking, they all grabbed their cameras and rushed out the door.

“It was very tense,” he said about that night. “I was getting calls from parents who were upset and worried about the well-being of their kids.”

Hundreds of police burst onto campus, and students, wearing a big sticker on their backs that read “student press”, ran to capture the scene. Officers began pushing protesters—and most of the student journalists—off campus, clearing the way to intervene in the occupied building with almost no witnesses. A few students managed to stay near the building, hemmed in by a line of police, while others returned to Pulitzer Hall, following Cobb’s advice.

The officers, in full riot gear, forced their way into Hamilton Hall, breaking the human chain by grabbing and striking protesters with batons and shields. One video shows a protester tumbling down the stairs, apparently unconscious. Protesters later reported a disproportionate use of force, with several sustaining bruises, cuts, and even fractures. During the raid, an officer’s gun accidentally discharged, according to the NYPD. The bullet struck a wall, and no one was injured. A total of 109 protesters were arrested.

“We were livid that the NYPD was called,” said Robe Imbriano. “That the dean who stands for freedom of expression, and who’s charged with protecting hundreds of students, is put in the position he was put in, to me, is unconscionable.”

While officers were arresting students, Jelani Cobb joined a news program on MSNBC by phone. “It’s tragic,” he said of the NYPD’s presence on campus. “It’s a very difficult thing to see.” According to colleagues and students, Cobb had opposed involving the police and had worked to avoid that outcome. Given his journalistic record, supporting a raid could have been seen as contradicting his principles. “My motivation was to try to forestall something like this happening,” he told the host that night.

He didn’t openly criticize the administration’s decision; instead, he sought to explain it—even as it put him in the uneasy position of justifying actions he had long scrutinized. He said he had received calls from “people high up in the state government,” asking whether those occupying Hamilton Hall were all Columbia students, and expressing concern about what outsiders “might be capable of.” “There was no way to verify that,” Cobb said. (According to the university, 13 of the 44 people arrested inside Hamilton Hall were not affiliated with Columbia.)

Two pictures from that night at Pulitzer Hall capture the extraordinary nature of the situation. One shows faculty members before the arrests. They are posing for the camera—Cobb smiling broadly, his own camera slung in one hand—in the lobby of the building, beneath a plaque that reads: “To educate the next generation of journalists.”

The second photo, taken after the arrests, shows a different scene: NYPD officers resting inside the same lobby—the only building still open on campus. They are slumped under the memorial honoring journalists killed in the war in Gaza.

“I saw the NYPD inside Pulitzer, and I lost my mind,” Taha recalled. “I think the NYPD should not have been in Pulitzer, but I don’t know what power [Cobb] could have had against the NYPD.”

The following day, Cobb sent an email to the Journalism School community recounting the events of the previous night. He listed them in real time, offering no personal commentary, but took care to emphasize the significance of his students’ work. “To our students: you are a part of history now,” he wrote. “Your perseverance during a confusing and challenging moment cannot be understated. You told the stories the global public deserved to hear. You helped the School to meet its mission.”

Jude Taha holds a profound sense of disillusionment with the Columbia University administration. It would be highly unlikely to hear her defend the institution in any capacity. However, she also believes it’s important to extend some understanding to Cobb regarding how he handled the situation. “Could he have done more?” Taha asked. “I think so. But do I believe he did the best he could with the circumstances he faced? I also think that.”

***

Cobb has reflected on what the events at Columbia mean for both the university’s history and the broader context of the country, but he believes it’s still too early to fully understand their impact. “We’re still in the middle of it,” he said.

A year after the encampment, the situation on campus had only worsened. With Trump’s return to the presidency, Columbia became a prime target. After canceling funding, the Trump administration said Columbia would have to comply with a list of demands to restore it, including banning masks (often used by protesters to shield their identities), formalizing a definition of antisemitism, and empowering internal law enforcement on campus.

By then, ICE officers were already being deployed to arrest Palestinians who had participated in the protests. Mahmoud Khalil was arrested in the lobby of a university building, even after he had emailed administrators asking for protection. “This is the first arrest of many to come,” Trump threatened on social media.

Other students, like Ranjani Srinivasan, an international student from India, also sought Columbia’s help after learning her student visa had been revoked. The university didn’t intervene; instead, it withdrew her enrollment. On March 11, she fled the country before ICE agents could raid her campus apartment.

“It felt like some kind of dystopia,” said Claudia Steenhard, a recent graduate and international student at Columbia Journalism School. “I can’t get my mom to come visit, but the ICE agent can just walk in and deport someone.” At a school where nearly 40% of students are international, anxiety was everywhere. Some Palestinian students were too afraid to come to campus. They attended classes online whenever they could.

At the school, the first official response after Khalil’s arrest came from Cobb himself. When he returned from Oxford, he held a town hall to address the crisis. “I was very impressed by how serious it felt when you walked into that room,” Steenhard recalled. Cobb, alongside professor and First Amendment lawyer Stuart Kale, informed students about the risks they could face while reporting and the tools available to them.

Cobb promised to do whatever he could to protect them, but was clear about his limits. He explained that no one could stop the Department of Homeland Security. “They needed to be aware of how limited my power was compared to the federal government,” he told me. “What I did not want was for my students to go out to report without having had an honest assessment of the level of risk involved.” Cobb shared their disbelief that the government no longer seemed bound by the Constitution.

He believes the university must defend students and their rights, but he also recognizes how difficult it is to stand against a government willing to break the rules. “What institution has more power than the government?” he asked me.

Columbia Journalism School released a statement addressing Khalil’s detention. “We are witnessing and experiencing an alarming chill,” they wrote. “We write to affirm our commitment to supporting and exercising First Amendment rights for students, faculty, and staff on our campus—and, indeed, for all.

A few days after the town hall, on 21 March, the university released a memo titled “Advancing Our Work to Combat Discrimination, Harassment, and Antisemitism at Columbia”. They had decided to accept some of Trump’s demands: banning masks, adopting a formal definition of antisemitism, and empowering campus security to arrest students. They were capitulating.

The move left much of the faculty in dismay. Some wrote to President Katrina Armstrong, warning she was making a historic mistake. Others voiced their anger on social media. Jameel Jaffer, director of the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia, called it “a sad day for Columbia and for our democracy.” Rashid Khalidi wrote an opinion piece in The Guardian, asking if Columbia still merited the name of a university. “It was never about eliminating antisemitism. It was always about silencing Palestine,” he wrote.

Julie Cohen, the Oscar-nominated filmmaker, resigned—along with three others—from her role as a juror for the duPont-Columbia Journalism Awards. “I felt like I needed to dissociate myself from Columbia,” she said in an interview with The Wrap.

Armstrong stepped down abruptly a week later. Claire Shipman was appointed acting president—the fourth president Cobb has known in three years as dean. (Shafik resigned in August 2024 following intense pressure from students and faculty.) “I’ve seen, firsthand, the devastating impact of antisemitism on our community,” she wrote in her first email to the community. “No member of the leadership team or the Board of Trustees ever notified ICE about any members of our community. Full stop.”

In May this year, Shipman faced the first major protest of her presidency. Dozens of students occupied a reading room in Butler Library and renamed it the “Basel Al-Araj Popular University,” in honor of a Palestinian writer and activist killed by Israeli forces. Public Safety officers blocked access to both students and journalists. When the activists attempted to leave without showing ID, officers used force to stop them, at times pushing students to the ground.

Shipman described the protest as violent and antisemitic and called in the NYPD. “Let me be clear, what happened today, what I witnessed, was utterly unacceptable,” she said in a video statement. Police stormed the campus and arrested 78 students; at least one was carried out on a stretcher. Shipman’s response earned praise from the Trump administration, which called her statement “strong and resolute.”

When I asked Jelani Cobb how he felt about Columbia caving to Trump’s demands, he paused for a few seconds before answering: he couldn’t say.

Does this create a moral dilemma for you? I asked.

“Yes,” he said. “It does.”

Cobb acknowledged that being dean comes with constraints—there are things he simply can’t say in public. Both roles, dean and reporter, he explained, rely on a deep respect for confidentiality. Still, those around him don’t see a split between the journalist and the administrator. Students and colleagues describe him as consistent in public and private. They point to moments like when he pushed to allow journalists onto campus, documented the protests with his own camera, or spoke with honesty during the town hall.

“I think Jelani has his heart in the right place,” said a recent international graduate of the Journalism School who asked to remain anonymous. The former student praised Cobb’s effort to protect students, but also expressed disappointment that the institution he leads hasn’t spoken more forcefully about the killings of Palestinian journalists or hasn’t sufficiently combated the assault on academic freedom and free speech. “It’s not about Jelani. It’s about Columbia and the role of faculty members as a whole,” he added. “Should the faculty do more? Should the institution do more? My answer is an emphatic yes.”

Cobb doesn’t disagree. He, too, believes more can be done. On April 21, 2025, the Journalism School—alongside The New York Times—hosted an event titled “The Fight for Global Press Freedom”. Among the speakers were journalists from Hungary, Brazil, and India. But at what has become the deadliest period for journalists in recent history, there wasn’t a single Palestinian voice on the panel.

During the Q&A, a reporter brought it up. “We have raised this point in statement after statement,” Cobb answered. He went on to note that the Journalism School has been the only one at Columbia to publicly mention the arrest of Mahmoud Khalil, and pointed out that it had also organized a talk with Palestinian journalist Motaz Azaiza. “We’re not perfect. We can do more,” he said. “But we have done some things in [an] effort to make sure that we highlight this issue.”

At the Journalism School’s May 2025 commencement, the lobby was bare. This time, there was no memorial wall honoring the more than 180 journalists killed since October 7. The school had taken it down shortly after the 2024 graduation, and students were unsuccessful in putting it back up. For the second year in a row, some students graduated feeling ashamed to be part of an institution they see as complicit in the arrests of their Palestinian classmates. Faculty members are also struggling. They recognize it’s a complicated time to be at Columbia. But the ones I spoke to agree that Cobb is the person they trust to guide them through the crisis.

“The school is on the frontline of what is really a battle for democracy and freedom of expression,” said Alexander Stille. “I think Jelani is likely to be listened to and to be an important voice in discussing how the university as a whole should address the pressures that it’s under.”

Sometimes, Jude Taha argued, power lies not only in disruption but in the slow, deliberate work of deconstructing the very institutions that uphold the system. “I think there is power in being in these rooms,” she said, recalling what Cobb told her when she was thinking about leaving Columbia.

“What if the next person is worse?” the international student asked. “We should push Jelani to do more, rather than have Jelani removed—because then whoever comes in, we’d have to push that person too.”

Many have asked Cobb if he’s considering stepping down. “I still think the most important thing I can do right now is what I’m doing,” he said. “I’m not over-inflating my importance, but I think I still contribute something valuable.”

For now, he is staying.