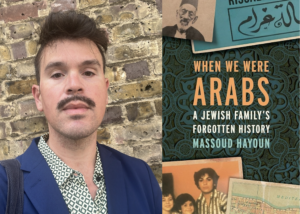

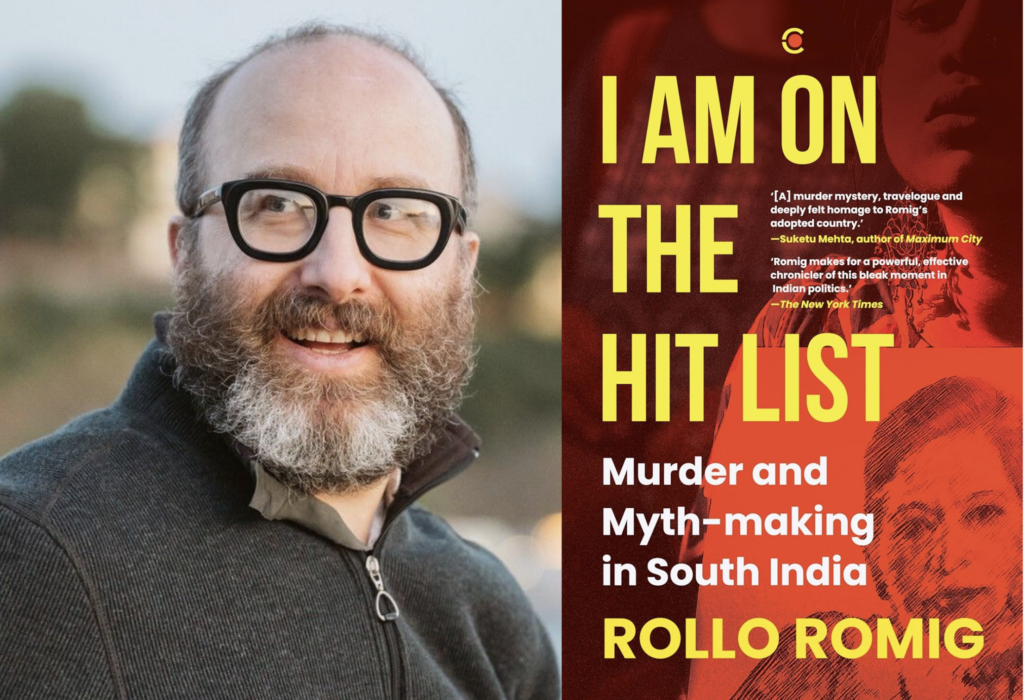

Rollo Romig on His Latest Book, I Am on the Hit List, and What We Can Learn From Gauri Lankesh

Rollo Romig, the journalist, critic, and essayist from Detroit, has been covering South India since 2013. His latest book, I Am on the Hit List (Context, 2024), now a Pulitzer finalist, is a culmination of his years of reporting on the region. The book traces the journey of Gauri Lankesh as a young journalist, to the fiery activist she would later become, to her eventual assassination in 2017 outside her home by radical Hindu nationalists.

The editor and publisher of a Bangalore weekly, Lankesh was a staunch critic of the Modi-led BJP government. Her murder became a flashpoint, with the BBC describing it as the most high-profile journalist murdered in recent years. Protests erupted nationwide, thousands attended vigils, and the incident ignited a debate about press freedom and authoritarianism in India.

I am on the Hit List is not just the story of an individual but also of a changing city (Bangalore), a changing state (Karnataka), and a changing nation.

Combining biography, political history, and reportage, Romig braids the story of Lankesh’s life and assassination with a sweeping account of India’s democratic unravelling—from bookshops and courtrooms in Bangalore to the ideological battlegrounds of modern Hindutva. One of the finest pieces of investigative journalism capturing the rise of majoritarianism and intolerance in modern India, I Am on The Hit List is also a love letter to those fighting against injustices everywhere.

By tracing Lankesh’s journey, Romig analyzes how democracies perish by expunging dissent. The book is both a tribute and a warning; it reminds us that speaking out has never been more dangerous or more necessary.

I first read I Am on the Hit List shortly after its release and was struck by the precision and empathy with which Romig tells Lankesh’s story. A few days later, I sat down with him over a virtual interview for a rich conversation spanning his love for Bangalore, his experience researching for the book, and his views on journalism, dissent, and the erosion of democracy in India and beyond.

What follows is an edited excerpt.

Amritesh Mukherjee: The first few chapters of the book detail your relationship with Bangalore. How has your relationship with the city evolved?

Rollo Romig: I’d been going to Bangalore pretty often for years at that point (2017), spending a lot of time in India. I started going frequently because my wife grew up in Kerala, and soon after we got married, I began reporting there, mostly for The New York Times Magazine.

It struck me, as it does anyone visiting India, how enormously diverse the country is. It drove me crazy that South India—distinct from the North and diverse in itself—barely registers for most Americans. A typical person here assumes everyone in India speaks Hindi.

So, my overarching agenda was to spread the word about everything unique happening in South India. I kept returning to Bangalore. Sometimes, I was reporting; other times, we’d use it as a home base. I love that city.

Bangaloreans complain a lot about Bangalore because it’s in this odd in-between place—it had a much quieter, easygoing, culturally distinct character earlier in the 20th century. Now, it’s this improbable, booming tech megacity. The way it’s exploded in size and wealth has been disorienting for many who grew up there. So many people have moved in that Kannada is now a minority language in Bangalore.

Honestly, I like that—the weird mix of things, the tensions. That’s how I felt about New York, where I lived for a long time. It’s frustrating, but that’s part of what I like—there’s always something to complain about, and it’s usually interesting.

Bangalore is extremely different from New York, but it has a rich literary scene. The bookstores are only growing. It’s incredible. I’ve never seen anything like it

And then there’s this Bangalore sensibility—still easygoing in many ways. Despite having the worst traffic in the world, it’s not as aggressive as Delhi’s. Vasudhendra, the short story writer, even dedicated a book to Bangalore traffic. I’ve done that too—spent hours in jams getting work done, even interviewing people over the phone.

AM: When did you first hear about Gauri Lankesh?

RR: I was in Bangalore for a month, right before Gauri was murdered. I returned to New York just a few days before that. I’d never met her, but I’d heard of her—and later discovered I knew many people who knew her.

Oddly enough, I first heard of her through a book I bought on Church Street: My Days in the Underworld: Rise of the Bangalore Mafia (2013), a memoir by an ex-gangster, Agni Sridhar. He used to be the top mafia don in Bangalore and is now a literary figure. It’s a very unusual gang-life memoir, which I recommend.

He shares how Gauri’s father, P. Lankesh, was a major Kannada writer who essentially invented the Kannada tabloid. Before Sridhar became a gangster, he was a disciple of P. Lankesh. Gauri, a teenager then, told Sridhar about a guy at her school who was harassing her. To impress her father, Sridhar dragged the guy to the outskirts of town and nearly killed him. The Lankesh family was not impressed, and Sridhar stopped hanging around them after that.

That was his first brush with the police—and my first encounter with Gauri’s name.

AM: Tell me more about researching I Am on the Hit List. What were the main challenges you faced, and how did you approach them?

RR: The main challenge was that I didn’t speak or read Kannada. In many ways, this is a book about Kannada literature. Gauri’s father was a major figure in that world. She came from that history and later pivoted from being an English-language journalist writing for mainstream magazines to becoming a radical Kannada-language journalist and activist.

Even though her father was a giant of Kannada letters, she had attended English-medium schools all her life and had failed her Kannada exams twice. She could speak it—what her ex-husband called rough, street Kannada—but she wasn’t fluent in a literary sense. Everyone, including her, agreed she wasn’t the ideal candidate to take over her father’s paper when he died unexpectedly in 2000. But she did. And to everyone’s surprise, she became fluent—maybe not perfect, but good enough to function as an editor. She even wrote in Kannada about her struggles with Kannada.

I never learned the language well enough, so I needed a lot of help. We think of other creative projects—like movies and music—as inherently collaborative. But we have this stubborn idea that books emerge from one person’s solo genius, probably because there’s one name on the cover.

Not a page of this book would have been possible without a lot of help. I relied on the work of hundreds of Indian journalists and needed a lot of translation help. One young woman in particular, Amulya Leona, who became a character in the book, helped me enormously. She translated so much—very little Kannada writing has been translated into English, so I needed a lot.

After Gauri was killed, Chandan Gowda, a great Kannada scholar and a close friend of hers, quickly brought out an anthology of her writings, a rich collection. But there was much more I wanted to read.

Beyond that, the charge sheet from the Special Investigation Team was over 9,000 pages long. I didn’t need all of it—much of it was technical—but hundreds of pages were valuable: statements from the 17 arrested accused, for example. Amulya translated all of it.

Plus, both of Gauri’s parents had written memoirs. Her mother’s, if anything, I found more interesting. Her mother wasn’t a writer; she ran a sari shop and was a businesswoman. But her memoir was captivating, where she’s very frank about her relationship with her husband, their family life, her own life, and her perspective on parenting and running a business. A great book, but it had never been translated into English. Nor had her father’s.

Amulya translated both—just so I could read them. I think I’m still the only person who’s read her English versions. I’d love for them to be published someday. She translated probably over a thousand pages and gave me access to the world of Kannada. That was just incredibly precious.

AM: Your book has different publishers inside and outside India—did you face any challenges with Indian publishers?

RR: That was definitely a challenge. It was very hard to find an Indian publisher willing to take on the book. Penguin, for instance—I published the book with Penguin in the US, but Penguin India refused to publish it. I had fully expected Penguin India to be my publisher, and it was a challenge to find someone else. I can’t just assume that was due to concerns about the political content—maybe they didn’t like the book.

Westland has been incredible. They continue to be the bravest major Indian publisher. I’m really impressed by their nerve, their smarts, and their savvy. It’s been a privilege to work with the people at Westland, particularly my editor, Ajitha GS. We made a lot of changes, which was gratifying. The bulk of the book is the same, but we cut out a lot of explanatory passages—stuff for American readers who don’t know much about India. It made the book lighter and leaner, without stopping to explain terms or concepts any Indian reader would be familiar with.

We also added back a lot of poetry. In an earlier version of the US edition, I’d included more, but we ended up cutting much of it. I quote a lot of Indian poetry because many of the people I was writing about happened to write poetry or had poems written about them. So we put it all back in.

About Westland, we’re very lucky to still have them. When it looked like Amazon was going to shut it down, it was enraging. It’s a familiar pattern—ultra-rich companies or billionaires buying things with long histories and destroying them. So yes, I’m really grateful that Westland has survived—and is thriving.

AM: I really loved the interluding chapters, especially the one titled “Doubting Thomas”—referring to one of the twelve apostles of Jesus Christ, who is known for questioning Jesus’s resurrection and is said to have brought Christianity to India in the first century. That chapter felt like a journey in itself: you start off believing in the idea that Thomas came to India, but by the end, you don’t believe that anymore. Was there a similar personal journey for you through the book? Were there ideas or beliefs that changed entirely?

RR: That’s a great question—I love it. Those interludes were an odd structural choice. They tell completely different stories and even take place in different states—not Karnataka. It just felt right, though I couldn’t always articulate why. But I think you’ve nailed one of the reasons—one I may not have fully realized myself—that the Thomas section is significant because it’s about evolving in one’s beliefs over time.

In that chapter, I’m the one who evolves. I begin excited about the idea that Thomas came to India from Palestine 2,000 years ago. By the end, I’m convinced he didn’t. That arc reflects one of the book’s themes: people can change. Dramatically.

We often assume people are fixed. But Gauri’s life is a striking example of change. People who knew her at different times described what sounded like two different people. A lot about her stayed the same—energetic, hospitable, angry, joyful—but there was a real transformation, too.

The shift in her politics and her journalism was profound. As a younger journalist, she wrote conventional feature stories with a classic belief in neutrality and objectivity, that personal politics and journalism should be kept separate.

But she came to see those as illusions, political positions in favor of the status quo. She became an outspoken radical. Some friends even described her as nearly ascetic—alarmingly thin, not eating enough, not taking care of herself.

Gauri was an extraordinary person. After her murder, she became internationally famous almost overnight, but I don’t think it was widely understood why. Even those closest to her were surprised by how many people came out to protest her death.

Her power wasn’t just in her public speeches—it was in the quieter ways she connected with people across communities. She had a rare talent for friendship and connection—the kind of deeply political work often dismissed as “women’s work.” It goes unseen until the person doing it is gone.

Being immersed in a life lived with such conviction, passion, humor, and joy made me think deeply about how I want to live. It made me reckon with my own approach to journalism. I have opinions. I have an agenda. I don’t see the point in pretending otherwise. When people say journalists should be neutral, what they should mean is: be scrupulous, be self-critical, be thoughtful, and listen—to everyone, not just “both sides.” Because there are never just two sides.

You don’t owe anyone the illusion that all arguments are equally valid. Some ideas are indefensible. Some are lies. And it doesn’t serve anyone to pretend otherwise.

AM: The Overton window—the range of ideas considered acceptable in public debate—has been shifting globally. The last US elections saw both sides taking traditionally right-wing stances. In India, you see widespread apathy toward discrimination, violence, and crackdowns on dissent. How do you deal with that shift in public attitude?

RR: I’ve been thinking about this a lot. I was immersed in the Indian context for years, and now we’ve had a very dramatic election here—somehow, a very different second Trump term. The parallels are obvious.

I’ve heard people say, after Modi was elected to a third term, that it’s a shift, that since he had to form a coalition this time, things have softened. I don’t think anything’s softened.

I think you’re right. If we’re hearing less about it, it’s because they succeeded. They broke democracy. They broke dissent—not all of it, but a lot. You’re not hearing the same voices of protest because they’ve done a really good job of shutting them down.

Institutions are broken. Safeguards are broken. Both countries are so used to thinking of themselves as democracies that we don’t really understand what it looks like when a democracy is lost. We had these cartoonish ideas—tanks in the streets—but it’s subtler.

One thing that struck me while working on the book was just how easy it is to lose democracy without realizing it. Even among well-meaning, sympathetic people, there’s not a full grasp of how bad things have gotten, which is partly by design.

The autocrat’s work includes masking the damage—making it feel like things haven’t changed. Many of the sources we’d rely on for information have been disrupted, diluted, or co-opted. There’s a flood of propaganda, trolls, and misinformation. It’s incredibly hard—even for generally well-informed people—to grasp the scale of the damage.

Take how bad things have gotten for Muslims in India. I go into this in the book—a whole chapter titled Electoral Autocracy that’s meant to be punishing to read. It’s very easy, even if you’re not anti-Muslim, to not fully understand it. Because part of what the state has done is segregate Muslims. If they’re no longer your neighbors or your colleagues, how would you have a firsthand understanding of what’s happening?

AM: Circling back to Gauri Lankesh—especially in North India, she wasn’t particularly well known during her lifetime. After her death, this image of her as a martyr created a certain narrative, not just around her as a person but also in her writing. Through your research, what were some misunderstandings you came across that you hope the book helps correct?

RR: After she was murdered, there was this assumption that she had been a kind of major national figure. I’ve seen foreigners describe Gauri as one of India’s most important journalists—a national icon. But she wasn’t—at least not before she died. She became famous after.

She was a local figure. In many ways, local figures are the most dangerous because they’re writing in local languages and reach local audiences.

I don’t think the Indian government is that worried about English-language journalists. They get a lot of international attention, but English-language journalism reaches a tiny percentage of Indians. The vast majority of journalism in India happens in other languages. So there’s a paradox: someone writing for a smaller, more local audience in a non-international language can be more powerful, more threatening to those in power.

At the same time, Gauri’s paper was incredibly small. They were talking about shutting it down just weeks before her death. She sold her life insurance policy to pay her staff. It’s not like she had this huge platform.

We don’t really know how to categorise someone like her. And we should do better than just reducing people to their professions.

AM: I come from a small, conservative town in India and a very conservative family. However, I grew up in a protected, secular environment, believing in constitutional values. Over time, I realized it was not the Hindutva groups who were the fringe—it was I, the English-medium student, believing in a fictional, tolerant idea of India. I wanted to know your thoughts on that. Has your conception changed?

RR: It’s a really interesting question. These ideas—what it means to be Indian, to be American, the American Dream, the idea of India—are fictions, stories told to create a national identity.

One of the most useful concepts is Benedict Anderson’s idea of “imagined communities.” Nations are fictional. Borders are fictional. It’s all made up.

But I can’t knock it entirely. These fictions are often how we hold our democracies together. Some of these fictions—like the idea of India being an incredibly pluralistic place—are made up. Not that India isn’t diverse, but the idea that it’s harmonious is a fiction, although valuable.

I still struggle with this. I don’t really know how to think about it. It’s something I thought about when Obama was running. He gave these flowery speeches about America and democracy. I remember thinking: ‘This sounds great—and it’s also total bullshit.’ But even though it’s made up, and he must know that, maybe that doesn’t make it meaningless. Especially now, when we’ve lost so much, and the idea of community has been trashed, you miss that old bullshit. It held things together and sometimes called us to be better.

Earlier, I was talking about valuing brutal honesty—and now here I am, partly endorsing myths of nationhood. I really don’t know how to think about this.

AM: As someone who’s both an outsider and an insider to India, how do you see the way forward? Especially since things have only escalated since you started writing this book. How do you process the shift in narrative?

RR: Despite everything, and this might be surprising given all the cynical things I’ve said, I’m pretty optimistic about the future. In one sense, because things can only get better. But I do think the seeds are all there for things to get better.

As I said earlier, it’s really easy not to understand how bad things have gotten. The flip side of that is, if the broader public did fully understand the extent of the damage, they’d be disgusted. I don’t think most people are evil.

You mentioned that I’m an insider and outsider at once—I’d say I’m overwhelmingly an outsider. I’m lucky to have married into an Indian family, so maybe I have more access than your average foreigner. But I’m still an outsider.

I keep thinking about Anand Patwardhan’s 2018 documentary, Vivek (Reason). It tracks the same set of murders I cover in the book. But Anand does something only an insider could. While tracking these disheartening assassinations and the rise of the right-wing, he intersperses them with clips of local resistance, mostly through music and performance. You’re watching this overwhelming, dark story, and suddenly, there’s this vibrant protest music. It’s extremely local, which is really important.

It’s discouraging to look at things at the national level—in both the U.S. and India. Honestly, it always has been. But on the local level, there are many inspiring happenings. And that’s where we, as individuals, have access and influence.

We vote for presidents and prime ministers, and it often feels like it doesn’t make any difference. But local elections do matter. Your neighborhood and your community—that’s where change really lives, where hope is. That was one of Anand’s most important insights in the film. When he cuts to the activists and artists, he’s not cutting to national figures; he’s showing hyper-local people doing real work in the streets.

Even as I’m completely dismayed by what’s happening in the U.S. nationally, I’m also excited about a mayoral candidate in New York City, Zohran Mamdani. We’ve got mayoral elections coming up, and he’s the most exciting candidate we’ve had in a long time.

That’s something Gauri understood incredibly well. Even though she was often in despair about what was happening nationally, she still knew the value of local work—of plugging into the community, staying engaged on the ground, and why the response to her death was so enormous.

She also knew how to make room for joy, humor, and celebrating small victories. We need to remember that.

AM: What are you working on right now? Current reads?

RR: I’m working with the Solutions Journalism Network, a New York-based organization with an international scope.

I’ve made the mistake myself—many times as a journalist—of writing stories on how bad a situation is and ending on a cynical note: “No one’s doing anything, and no one ever will.” Sometimes, that’s true. But often, people are doing things. It’s not in our default journalistic habit to focus on those efforts. We’re trained to describe the problem in excruciating detail and depress everyone.

But people want to hear about real solutions when they exist. That’s what Solutions Journalism Network tries to foster.

I’ve been writing a lot about video games lately. I think they’re really misunderstood; there’s some fascinating creative work happening in that space. I did a piece for The New York Times a few months ago about Studio Oleomingus, an Indian game studio whose games comment cleverly on Indian politics and the colonial legacy. There’s real artwork being created in that form, and I’m trying to spark more conversation around that because it’s exciting.

Reading-wise, I’ve been catching up on 19th-century novels lately. I just went from Jane Austen to Sherlock Holmes. It’s very comforting reading, especially in times like these.