Photo Essay: In Kashmir, after deadly military conflict, a village hero who will never return home

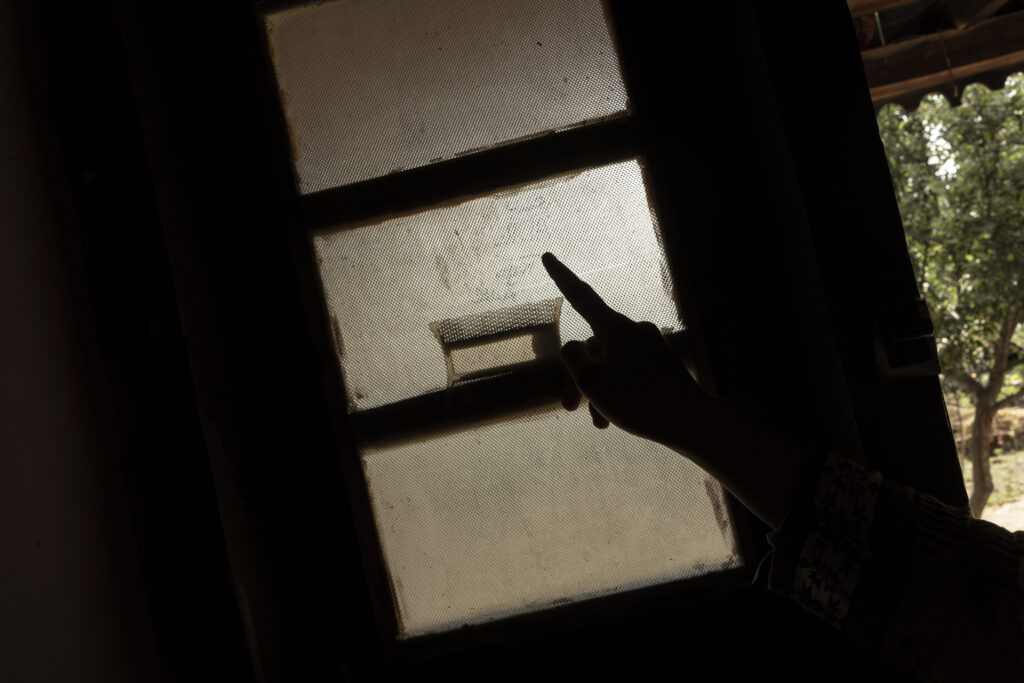

In a small purple-walled room, Baby Jan rests her eyes on a corner where, until just three months ago, her eldest son Adil used to sleep. Outside the house, just meters away at a graveyard, Adil’s younger sister Asmat Jan points to an elevated pavement. “He would often sit here by himself under the cool breeze of these trees,” she recalls. “Now he lies buried here.”

Ever since Adil’s killing, people keep visiting to offer condolences. The family huddles in a room pouring out their memories of him. It’s how the family tries to come to terms with his death, especially his siblings who can’t help thinking of the fateful day. Questions abound, but answers are few.

On 22 April in Pahalgam’s Baisaran Valley in India-administered Kashmir, 26 men were massacred in a gun attack. All the victims were Indian tourists, save one from Nepal and a local tourist guide—Syed Adil Hussain Shah. People in different parts of Kashmir protested the killings.

India blamed its arch-rival Pakistan for the attack, but Pakistan denied any connection. Since 1989, Kashmir has witnessed an armed rebellion against Indian rule; tens of thousands have been killed in India’s military crackdown ever since. Both the nuclear states claim the region in its entirety but control only parts of it. Most in Kashmir, however, favor independence or merger with Pakistan.

The police claimed three local rebels and two Pakistani militants were involved in the massacre, releasing sketches with a bounty of Rs 2 million (over $23,000) on each. Indian forces blasted over a dozen houses claiming they were homes of militants, a pattern that has emerged in recent years of punishing families of suspected rebels. Locals said several neighboring houses were also destroyed.

The night of 6-7 May, however, witnessed a rare escalation in the South Asian neighborhood when India conducted missile attacks against what it called “terror infrastructure” deep inside Pakistan. Pakistan said the attack targeted civilians, killing dozens, including women and children. At least 15 civilians were killed in the Poonch region when Pakistan retaliated. The world watched in alarm as the two nuclear powers turned the region into a battlefield until US President Donald Trump announced a ceasefire.

Questions with no answers

While Kashmir limps into a semblance of normalcy, as it usually does, Adil’s absence lingers. As mourners keep pouring in, the family pieces together the bits of information from the locals. But nothing brings much clarity.

“I went asking scores of people around for clues to my brother’s last moments, but nobody has answers,” says Noushad, Adil’s younger sibling. The thought often makes him restless. “Nobody is asking them the right questions,” he says, adding that the media has been incompetent in holding the administration accountable.

Several eyewitness accounts have suggested local guides tried to intervene during the attack, but Adil’s family says nobody could recall anything in detail. “His fingers were mutilated, perhaps because he tried to snatch a weapon,” Noushad says. “He could never stand injustice.”

The day his brother was killed, Noushad had left home early for work—whenever the opportunity arose, Noushad drove a cab to earn a living. “I didn’t see Adil that day. I assumed he would not go to work as it had rained, which makes the horse track muddy and the terrain too difficult,” Noushad says.

Adil, 30, was the eldest son in the family and the primary breadwinner. Finishing school, he had started working as a tourist guide to provide for his parents and younger siblings. Taking tourists for horse riding up the Baisaran Valley, Adil earned around $3 a trip.

In the videos that emerged after the attack, gunshots echoed in the meadows of Baisaran as tourists, stunned in horror, cried out for help. Bodies lay around, near and far, scattered across the field. The intensity of the attack unfolded as the death toll escalated.

Siblings’ love as a casualty

Asmat Jan sits against a wall with teary eyes, recollecting the conversation with her elder brother the day of the attack. The two were close to each other, so much that Adil got her married to a cousin in the neighborhood. “He would tell me he didn’t want me to be away from his eyes,” she says.

“That day I insisted with him not to go to work,” she recalls. “My heart wasn’t ready to let go of him, but the burden of responsibilities would not allow him to stay.”

In Adil’s room, his father Syed Haider Ali Shah sits in silence. Haider was a horse rider and tourist guide, too. But keeping unwell since his youth, he couldn’t provide much for the family. Adil stepped in and took up his work. “He started working soon after finishing school. The day of the attack, he went to work so there was money to buy my medicines,” the ailing father says.

Adil held the fort together—for the family he was a pillar of strength, for his sisters their best friend.

“I was really close to him,” recalls Ruvaisa Jan, the youngest among the six siblings, as she folds away her late brother’s shirt. “I was fond of doing his chores. I would keep his clothes ready when he had to leave for work. Now that he is gone, I have lost interest in everything.”

In 2019, Adil got married but separated a year later. “It was a troubled marriage,” Noushad says. Still, the family hopes the government aid to his widow would bring Adil peace hereafter. Adil’s youngest brother, too, has been offered a job. “But nothing can pay the price for his life,” Noushad says, referring to the compensations the family received from government officials, who sparred over taking credit for the aid.

Ruvaisa recalls her memories of Eid earlier this year. “This is where we were sitting, planning for a picnic,” she says, pointing to a patch of grass in their courtyard. “It is hard to believe he’ll never return to celebrate Eid with us.”

Outside the home, a stream gushes through the village. But Asmat’s memories of her brother remain frozen in time. It is all she has left of him. As we walk down, she recalls her childhood. “On his shoulders, Adil would carry me to the stream, or to the local shop to buy my favorite snacks. Nobody could care for us sisters like he did. Now we’re here, and he’s gone.”

Media’s criminalization of Kashmiris

Soon after Adil’s death, Noushad recalls scores of media persons, many from India, hounding him and repeatedly asking him about his thoughts on the attack. “What would my thoughts be? On an attack that killed my brother?”

The family has been monitoring the news since his killing, when several Indian news channels went on a rampage against Kashmiris and Indian Muslims. “Most of them were in search of propaganda and controversies, but we kept saying we are mourning the loss of all the lives lost,” Noushad says.

In the aftermath of the military conflict, several videos from Kashmir flooded the internet—people being recorded without consent by Indian journalists and content creators, asking them to chant “Pakistan Murdabad,” “Jai Hind,” “Bharat Mata ki Jai” or provoking them to speak against Pakistan on camera. People were seen even asking to not be recorded but in vain, as mics and cameras were shoved at them.

“You see how businesses have been affected. Why would we celebrate,” Noushad asks. “Why does the media project it brought us joy?” If Hindus were the only targets, Noushad says, “why did they kill my brother?”

The attackers had no sympathy for humanity, he says. “Adil was shot twice in the chest. And in the neck. Also, in the arm.” He was intolerant towards injustice, he insists. “He must have tried to stop the attackers, and in the scuffle lost his life.”

In India, however, hate speech against Kashmiris increased as the media engaged in war mongering. Kashmiris in various Indian states faced attacks from the public. The Association for Protection of Civil Rights recorded 21 incidents of anti-Muslim violence, intimidation and hate speech across the country in the days after 22 April.

Adil’s brother and father were also twice summoned to the police station. India’s National Investigative Agency, too, visited their home. “We lost our family member yet the administration is somehow not answerable to us,” Noushad says. “Adil’s phone remains in custody. It hasn’t been returned to us.”

Ruvaisa adds that all the memorable photographs she had with her brother are on that phone. A web of investigations has robbed her of those precious photographs. “I wonder if I’ll ever be able to look at them again.”

Adil’s final journey home

Noushad was driving from Aru to Chandanwari in Pahalgam when he got a call from his cousin inquiring about the chaotic scenes unfolding in Pahalgam’s main taxi stand. He thought there was an accident, and told his cousin he was away and could not confirm anything.

The next call he got was from his wife informing him about the attack in Baisaran. “I called Adil but his phone was out of reach,” he says. He kept calling him but could not gather any whereabouts. In the evening, Noushad anxiously tried again; the call got through but nobody answered. “I got more worried as it was getting darker.”

He soon called a driver accompanying a police official that day and with access to the hospital. Through a cousin, he was informed that Adil had been killed and the family should come to the hospital.

Noushad rushed with some of his neighbors but was told the bodies were shifted to Srinagar. He was given the number of an ambulance and asked to follow it. “In Srinagar, we waited all night. In the morning, after autopsy, the bodies were sent to the police control room. Then we were handed over Adil’s body. We came home in the afternoon.”

A crowd of mourners—men, women and children—had gathered to offer Adil’s funeral prayers and to bid farewell to the village braveheart. Word had spread that he had died saving lives, and the village laid their martyr to rest in the ancestral graveyard.

“Yaad aati hai bahut,” Asmat whispers at her brother’s grave, as if speaking to him. “I miss you so much.”

“He would tease me that he’d adopt one of my kids,” she says. Her two kids, whom Adil loved dearly, keep asking about their uncle. Holding back her tears, she tells them he’s at work. “He’ll be home soon.”