A Man in the sun – Reflections on decolonisation, what it means, how does it apply to various areas of human knowledge

Decolonisation isn’t simply a matter of expunging an occupying power, but of subverting the regimes of order it imposes on the world—of tearing away its masks of conquest, to use Gauri Viswanathan’s memorable phrase.

Steven Salaita, Decolonisation: Survival: Water: Life, 2019

This is an essay without reason. It emerges as a result of recent discussions with a friend and colleague about decolonialisation–what it means, how does it apply to various areas of human knowledge, and what can it mean for photography. Actually, this essay without reason emerges as a result of discussions at The Polis Project as we design a “Decolonise Photography” workshop series. Our discussions have led us to think about what new and different ways of seeing and doing could emerge in a documentary and photographic practice that recognises that “…the target of epistemic de-colonisation is the hidden complicity between the rhetoric of modernity and the logic of coloniality,” and is based on a need to learn to “unlearn” [See Walter Mignolo, Delinking: The Rhetoric of Modernity, the Logic of Coloniality and the Grammar of De-Coloniality, Cultural Studies, Volume 21, 2007].

There are many who are sceptical and critical of the current decolonial moment. There is now a widespread backlash against decolonial projects, aided and abetted by this current political moment of politically correct racism, popular authoritarianism and ethnic nationalism. Students who refuse Eurocentric histories, erasure of the Other’s suffering, colonial historical teleologies, concocted knowledge genealogies, the silencing of resistance historical and present, the elision of evidence of non-European scientific, cultural, social and artistic influences and more, are often accused of being ‘sensitive’ or ‘petty’ or ‘spoilt’ and unwilling to accept a ‘hard, tough education’. These critics assume a ‘correct’ set of knowledge, which is precisely what is being questioned. It is difficult to take this backlash seriously, emanating as it is from the pens and persons of the established, the privileged and the cock-sure–precisely the group and structures of thought that decolonial projects take direct aim at. If the first European /Western intellectual reaction to the Other speaking back was Postmodernism, the second European reaction seems to be nostalgia and racism. What these detractors reveal is a profound lack of understanding of the act of critique, which, to quote Foucault, is always “…a matter of pointing out what kinds of assumptions, what kinds of familiar, unchallenged, unconsidered modes of thought the practices that we accept rest upon.”

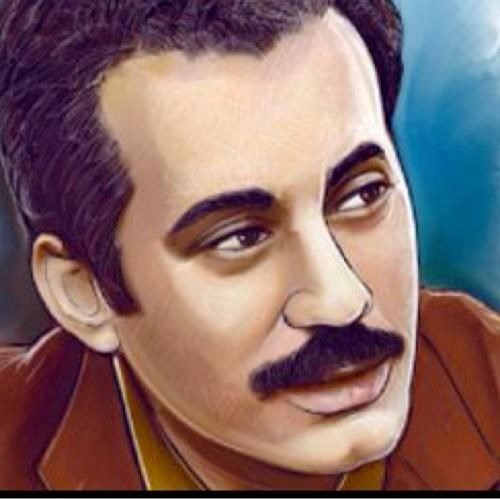

Ghassan Kanafani was one of the clearest-minded voices in the Palestinian’s struggle for justice and liberation. The child of Palestinian refugees, his family fled their home in Acre, Palestine, in 1948. He later began to write while teaching at a school in a refugee camp, using his short stories to help his students contextualise and articulate their lives. He was a key member of the Palestinian Front for The Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), a revolutionary socialist organisation led by the charismatic but infamous Palestinian resistance leader George Habash. (Aside: Most people do not remember, but in 1992, the PLFP opposed the Oslo Accords, and broke with Arafat, warning him of the pitfalls and traps ahead.) Kanafani was unapologetic, in ways that Fanon would have understood, of the need to fight and confront the coloniser on his terms. In a beautiful letter to his son, he argued that

Do not believe that man grows. No; he is born suddenly – a word, in a moment, penetrates his heart to a new throb. One scene can hurl him down from the ceiling of childhood on to the ruggedness of the road.

But he was no mere firebrand but a brilliant political thinker, strategist and novelist. His novel Men In The Sun, written in 1963, remains one of the subtlest and most beautiful of modern novellas. It is still the only book I know that powerfully and vividly captures the dilemma of the Palestinian who chooses death if he is to live.

The coloniser has never feared the violence of the colonised because he knows that the advantage of violence, and the organisational ability to impose it, is entirely with the coloniser. In fact, a coloniser welcomes the violence of the oppressed because it offers a justification for further colonial violence, projecting barbarism, madness and deviancy onto the oppressed and absolving the coloniser of the need for explanation or justification. The Israelis assassinated Ghassan Kanafani on 8th July 1972. He was killed in Beirut by a car bomb that also killed his 15-year-old niece, Lamia, who was with him at that time. The coloniser has never feared the violence of the colonised because he knows that the advantage of violence, and the organisational ability to impose it, is entirely with the coloniser. In fact, a coloniser welcomes the violence of the oppressed because it offers a justification for further colonial violence, projecting barbarism, madness and deviancy onto the oppressed, and absolving the coloniser of the need for explanation or justification. What the coloniser has always feared is the ability of the colonised to speak back and to articulate an alternative narrative. The most radically clear voices–the ones that reveal the hypocrisy and emptiness of the coloniser’s claims to civilisation, justice, equality, reason and truth–are the ones that are eliminated: Biko, Malcolm X, Lumumba, Kanafani and the list goes on.

But I want to return to this interview, a transcript of which follows below. I drifted to this interview while thinking about decolonisation because it is a vivid example of the Mignoloian demand that we always remain cognisant of “…the hidden complicity between the rhetoric of modernity and the logic of coloniality.” Here, in this interview, we see how a ‘modern’ discourse of ‘peace’ and framing of a narrative that places parties into ‘good’ and ‘bad’ opponents is undermined and taken apart. I have taken the trouble to add some editorial comments to the transcript to help us see and understand what Kanafani is actually doing as he confronts this journalist’s presumption and violent words. What follows is a short, near-the-7-minute clip from a longer interview.

| Original Interview Text | Analysis | |

|

Interview Preamble: “Of the eleven Palestinian guerrilla movements, the most RADICAL of all is the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, the PFLP. The Popular Front is now so well organised that it even has its own daily newspaper, with a claimed daily circulation of 23,000. It was the Popular Front that HIJACKED and BLEW UP three jet aircraft at Revolution Airport in the Jordanian desert. And it was the Popular Front that DYNAMITED the Pan American jumbo at Cairo. The Beirut leader of the Popular Front is Ghassan Kanafani. He was born in Palestine but FLED in 1948, AS HE PUTS IT, from “Zionist Terror”. Since then he is been PLOTTING the DESTRUCTION of both the Zionists and the reactionary Arabs.” |

|

The preamble to the interview, although couched in seemingly neutral terms, when examined carefully, reveals a clear understanding that the Palestinian struggle is manned by illegitimate, irregular, and unofficial military actors i.e. guerillas. They carry out irrational, inexplicable violence-hijack, blew up, dynamited. Kanafani is presented as having ‘fled’, not expelled, and pointing fingers to “Zionist Terror”, as he claims, and not as confirmed by fact. He plots, schemes destruction, hence, an irrational, violent and criminal type unfit for civilised and normal society. All this is offered before Kanafani has even spoken a word, and hence, the introduction immediately describes him as basically an unrepentant, irrational, terrorist. |

|

Reporter: It does seem that the war, the CIVIL WAR, has been quite fruitless. GK: It is NOT A CIVIL WAR. It’s a people DEFENDING their selves against a fascist government which you are defending because just King Hussain has another passport

|

|

Kanafani immediately challenges the framing of the situation. It is not a ‘civil war’ i.e. between two factions or sectarian groups that belong to one entity i.e. Jordan. He does so to make clear that the Palestinians are not Jordanians, but Palestinians. He reframes the argument to underline that the Palestinians are engaged in a defensive struggle against colonial power, or more specifically, the Jordanian collaborators with the colonial settler state of Israel. |

|

RC: …or a CONFLICT. GK: It is NOT A CONFLICT. It is a LIBERATION movement fighting for JUSTICE.

|

|

Again, Kanafani immediately interrupts the journalist and refuses his framing of the situation. The entire question is undermined, and dismissed. A conflict suggests equal opponents, a battle without history, a mere fight. Kanfani wants him to acknowledge, and insists on it being recognised that this is a struggle for liberation, an honourable and just and legal struggle, |

|

RC: Well WHATEVER might it be best called… GK: It is NOT WHATEVER, because this is WHERE THE PROBLEM STARTS. Because this is what makes you answer all your questions…ask you all your questions. This is exactly where the problem starts. This is a people who is discriminated, is fighting for his rights. This is the story. If you will say it is a civil war, then your questions will be justified. If you will say it is a conflict then, of course, it is a surprise to know what’s happening.

|

|

This is the harshest, but clearest moment in the interview. Kanafani tears at the journalists’s colonial arrogance by mocking him, and revealing to him his ignorant misuse of words, and how words frame narratives, and narratives frame questions, and, without his actually saying this, how questions frame ideas of truth, justice and legitimacy. Kanafani, the Other, understands that language, words, narratives are as much a part of this liberation struggle, while the ‘educated’, ‘sophisticated’ journalist is revealed for the stenography of power that he has come to perform. ‘Not whatever’, is Kanafani’s turning the tables on the reporter, making clear that although he does not speak in his native tongue, he knows and understands its political and lethal implications. |

|

RC: Why won’t your organisation engage in PEACE talks with the Israelis? GK: You don’t mean exactly peace talks, you mean CAPITULATION, surrendering. |

|

The framing of the question, despite Kanafani’s previous insistence on this being a liberation struggle, is immediately placed on the PFLP for ‘not engaging’ in ‘peace’ talks. Kanafani is up for the challenge, immediately attacking the liberal bromide of ‘peace’ and insisting no the human demand for justice. He understands that the peace of the weak is a capitulation, not a negotiation. He underlines this very argument in his next answer where he says that to talk to a coloniser is the “…kind of conversation between the sword and the neck, you mean?” That is, peace talks with a coloniser are death talks, as it is the coloniser who is neither interested in talks, or peace, but determined to take it all. Once again, Kanafani reveals are far truer, as confirmed by history, understanding of his enemy than does the reporter, who is still convinced that he is speaking to an unrepentant and irrational mass murderers, and continues to speak him condescendingly. |

|

RC: Stop FIGHTING. GK: Talk about stop fighting, why? RC: Talk to stop fighting, to STOP THE DEATH AND THE MISERY, the destruction, the pain. GK: The misery and the destruction and the pain and the death OF WHOM? RC: Of Palestinians, of Israelis, of Arabs. GK: Of the PALESTINIAN PEOPLE who are UPROOTED, THROWN in the camps, living in STARVATION, KILLED for twenty years and FORBIDDEN to use even the name Palestinians. RC: They are better that way than dead, though. GK: Maybe to you, but to us it’s not. To us to LIBERATE our country, to have the DIGNITY, to have RESPECT, to have our mere HUMAN RIGHTS, is something as essential as LIFE ITSELF. |

|

This entire exchange is Kanafani’s determined attempt to contextualise and to name. He refuses the journalist’s ahistorical, decontextualised and misleading use of words such as ‘fight’, and ‘misery’ and ‘destruction’. Kanafani understands that the coloniser inflicts misery, destruction and death, but then feigns innocence, and attempts to explain everything is mere violence. Kanafani wants the journalist to speak in specifics, to speak of Palestinian suffering, and to speak of liberation, of dignity and rights. He is saying to the journalist, that the Palestinians are fighting for ‘life itself’, because they are dead as they have been relegated to their refugee and dispossessed status already. This is a powerful moment of a colonised man insisting on naming himself, his struggle, the meaning of it and the righteousness of it, all that which has been denied him by European / colonial settler narratives within which he is not Man i.e. the subject of humanity or legality or concern for justice. |