Using the tools of legal anthropology, Padmini Baruah looks at the complex history of migration in the State of Assam; at the attempt to detect “foreigners” that has led to the evolution of a legal system biased against people from ethno-religious minority communities; and at the process leading to the deliberate creation of stateless people.

By Padmini Baruah (With inputs by Aman Wadud)

26 August 2020

The story of citizenship in India always begins and ends with seemingly innocuous paperwork. If one’s citizenship, as Hannah Arendt has said in The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), is the right to have rights, then documentation acts as one of the most formidable gatekeepers. Research has indicated that around 40% of the people in low-income countries do not have identification documents, with women and the poor being especially vulnerable. This identification crisis has direct effects in terms of access to government services and resources, but in its most extreme form, it can have dire consequences on the very existence of one’s status as a citizen. In the northeastern Indian state of Assam, this challenge has manifested in a statelessness crisis in the last few decades, as more than 130,000 people have been stripped of their citizenship due to their inability to prove it. This process is often arbitrary and arduous, hinging upon the technicalities of legal hurdles that can be insurmountable. In this essay, I take a closer look at the challenge of proving citizenship in India through the lens of one of the multiple cases that have been adjudicated over the years. Through this narrative method, I aspire to humanize the journey of navigating the citizenship process and reveal step by step the temporality, social context and agency of a suspected outsider as she jumps through the hoops of bureaucratic process.

The tale begins in the month of August, 15 years ago, with the turbulent Assamese monsoon looming in the horizon. Ruksana Begum [name changed] has fallen under the radar of the Electoral Registration Officer (ERO) of the Jaleshwar Assembly Constituency in the Dhubri district of Assam. Situated next to the banks of the river Brahmaputra in the western border of Assam and flanked by Bangladesh, Dhubri is a district with 80% of Muslim population. Ruksana is Muslim, and Bengali, and lives in a village called Fulpur, small enough to be unplottable. Her identity carries weight in the State. Since the British annexation of the territory in the 19th Century, Assam has experienced a flux of migration as a result of colonial policies. Most of the people migrating in the late 19th – early 20th Century were laborers brought in to expand agricultural production, creating a peasant community that was primarily composed of the Bengali Muslims. Moreover, the colonial government brought in a class of Bengali bureaucrats to administer the State, alienating the native Assamese population. The combination of these decisions created tensions between the two communities. This memory of Bengali dominance in the colonial era and the positioning of the Muslim as the “other” continues to remain alive among the indigenous Assamese people. Ruksana, therefore, is not merely a poor Bengali Muslim woman residing in Assam – she is the site of generations of suspicion, hate, and xenophobia. She now finds herself caught in the complex tangle of bureaucratic and judicial processes, beginning with the ERO process.

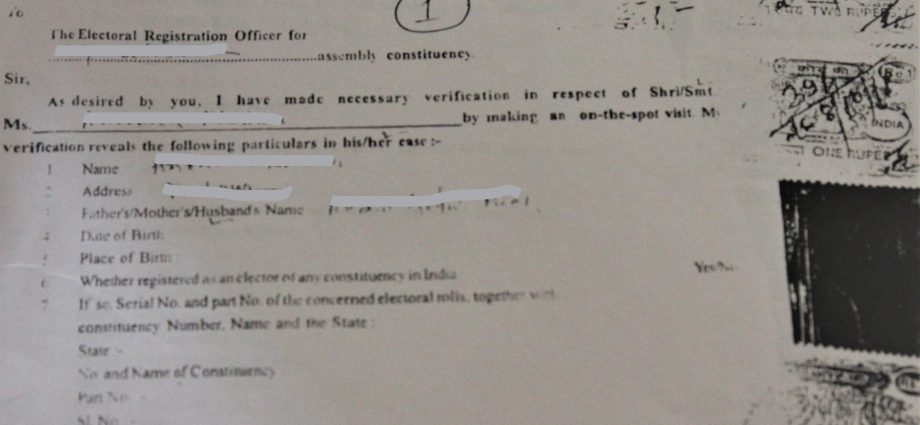

The Electoral Registration Officer plays the critical role of ensuring that the electoral rolls are up-to-date. These electoral rolls filter out who is eligible to vote in the country, effectively curating who fits within the definition of citizen. In Assam, between the citizen and the non-citizen, the Election Commission has the power to place people within the twilight category of the D-Voter, or the Doubtful voter. Once the Commission determines that a person is potentially a D-Voter, a verification process is initiated. This verification is carried out by the Local Verification Officer under the Election Commission. The proforma for verification has numerous probing fields that the officer must fill up before arriving at a conclusion. Is she already registered as a voter in any constituency? Are her parents? What is the officer’s assessment on the dialect she speaks? Can she produce previous electoral rolls, land records, birth certificate, passport, marriage certificate? Did she migrate to Assam? Which year did she migrate?

The form is startlingly blank in Ruksana’s case – only her name, address and father’s name are mentioned, along with the word “absent” next to the entry “Inquiry officer’s assessment on the dialect spoken.” This blank document, with no demographic information, documentary verification, or grounds for the doubt arising in the first place is the basis for the ERO to decide whether to consider Ruksana a citizen or not. Yet, the stark black letters of the “Format for making reference to the Competent Authority,” a document issued by the ERO following verification, pronounce an unequivocal verdict: the ERO has found reason to believe that Ruksana’s citizenship is in doubt and she now has to clear the next hurdle – a trial before the Foreigners Tribunal (FT).

The Foreigners Tribunal finds its home under the Foreigners Act, 1946. This Act defines a foreigner as “a person who is not a citizen of India,” and places the onus of proving that one is not a foreigner on the persons themselves. The FT was set up through an executive order in 1964 and is a quasi-judicial body that performs the task of filtering out whether or not one is a foreigner. Adjudications are made by members who are appointed by the State government. Thus, in the FT system, the power to make appointments is in the hands of an executive body, indicating a lack of judicial independence. The executive also has the power of reviewing the FT members’ performance and awarding them with incentives. Since performance is measured in terms of how many people are declared foreigners, FT members are quick to rule against the persons under suspicion.

A notice is sent to Ruksana 12 years after she is first tarred with the label of being a D-voter in 2005. The text is succinct – she is suspected of having entered Assam after 1971, and must present herself before the Foreigners Tribunal, Dhubri, within three weeks for a hearing. This date is of immense significance in the political history of Assam. 24 March 1971 is what is known as the “cut-off” date as outlined in the Assam Accord: foreigners who enter the State after this date sans paperwork are to be considered illegal immigrants. The Accord represents the culmination of seven years of a massive anti-immigrant movement in the State. Sparked off in 1979 after widespread outrage over the presence of alleged immigrant names on the electoral rolls, the Assam Agitation evoked loyalty to Assamese autochthony and was marked by turbulent protests, economic blockades, and heinous ethnic violence. The movement demanded that “foreigners” (often embodied by Bengali Muslims) be expelled from the State, and their names deleted from the electoral rolls. Resolution was only achieved after multiple rounds of negotiation with the State government, and the compromise that led to the amendment of the citizenship law of India as it applied to Assam. Foreigners who entered the state between 1966 and 1971 would be deleted from the electoral rolls and disenfranchised for 10 years, while exercising other rights available to citizens, and be absorbed into the body of the citizenry after that period. Those who came after that date would be regarded as illegal immigrants and be deported.

Receiving a notice from the FT, therefore, marks the first step of a process built to have far-reaching consequences. For Ruksana, this notice sets off a scramble for documentation – she must now bolster her claim to citizenship through an extensive paper trail, subject to intense evidentiary standards. This task amounts to squeezing blood from a stone; there is no administrative pronouncement or legal precedent that lays down what amounts to a valid document for proving citizenship. Indian courts have applied different standards in this respect – it has been held, for instance, that neither birth certificates nor passports are conclusive proof of citizenship. Aadhar cards, taxpayer identification cards (known as PAN cards), land documents, and bank documents have all been considered invalid for proving citizenship. Yet, Ruksana has armored herself with all the paperwork she can muster with the help of her family: land records in the name of her father, copies of electoral rolls from 1966 and 1970 featuring her parents’ names, a marriage record, sales deeds for land that her father bought in 1971, her Madrassa examination admission card, and her school certificate. The challenge she is faced with is to demonstrate before the FT that this assortment of documents proves beyond doubt that she is a citizen of India.

Ruksana’s narrative before the Court is heartbreakingly mundane. There are stories woven between the lines of her written statement. She was born in a village called Nayapara, where she was raised by her parents, who were both Indian citizens. They have exercised their right to choose their own government in 1966 and in 1970. She pleads that her lineage goes back two generations – her father, Rafique, was born to Indian citizens himself. He managed to buy land and send her to school. She married a man and moved into his home, her future tied to his. Her case is brief – she was born on this land, grew up here, studied here, was married here – she has known no other reality but that of being Indian. Her father stands witness to this fact before the FT.

The FT member parses this story through the filter of the arbitrary legal process, brusquely dismissing her hard-produced pieces of evidence in terse legalese:

“… land documents … some portion of the documents are damaged and illegible”

“… marriage Kabinnama [marriage settlement] which was registered at sub-Register office … but O.P. [Opposite Party] did not call for the concerned … official to prove the content of the deed”

“… in the admit card the father’s name of the O.P. … totally blank”

“… leaving certificate … year and examination portion of the certificate is found damage [sic] … did not call for the concerned certificate issuing authority”

“… failed to establish linkage with … father by any cogent admissible evidence”

“… highly suspect and wholly improbable”

FTs are notorious for applying extraordinarily stringent and selective standards of evidence. The standard that is applied for citizenship cases is at par with criminal trials. In Indian evidence law, there are two kinds of documents that can be brought before a judicial body – public and private. Public documents proving citizenship, such as voter lists, must be officially certified. To prove private documents, such as certificates issued by the village headman, marriage certificates, Panchayat certificate proving lineage with the father, the issuing authority has to mandatorily testify in person before the FT. The system is based on patrilineal descent – thus even if Ruksana’s name might be on a voter list and on her school leaving certificate, it is not enough. There must be proven linkage with her father’s side of the family. As in Ruksana’s case, the FT rarely considers deposition by family members (who are themselves citizens) attesting to their relationship in clear contradiction to the principles of Section 50 of the Indian Evidence Act, which states that the opinion, expressed by conduct of a person who has a familial relationship that has to be proven is relevant. Her father’s word amounts to nothing before the Tribunal. Ruksana’s gender has come in the way of her being able to acquire the relevant evidence to prove her case.

The FT, Dhubri unceremoniously pronounces Ruksana a foreigner of the post-1971 stream. The Tribunal orders the Superintendent of Police to take her into custody and keep her in an “appropriate place” until she can be “pushed back.” Her entire family has, by order of the Tribunal, now been placed under suspicion and will be likely hauled up before the FT soon. The “appropriate place” as quoted in the judgment, of course, is the nightmarish reality of the detention center. Built into six prison complexes across Assam, detention centers house those who are in the limbo of statelessness. Deprived of access to even the basic rights that criminal convicts enjoy, detainees, live a half-life, waiting for a release that never arrives. For Ruksana, this could mean separation from her family, no healthcare, rights, bail, or parole, and in extreme cases, death. There is no direct way to appeal this – any challenge can only happen through filing a writ petition in the High Court, which is arduous, expensive, and not likely to be in her favor due to the preponderance of the judiciary to rule against declared foreigners.

This nefarious process is how the State dances with crimmigration – a term used to refer to the intersection between criminal law and immigration law in the Assamese context. As in the USA, the boundary lines between citizenship laws, procedures, and practices and crime control strategies are increasingly blurring, and there are now overlaps in citizenship and criminal matters. FTs, as evidenced from the case above, have become draconian institutions responsible for declaring people as illegal immigrants arbitrarily and on extremely flimsy grounds. The Police are a key player in this process, as they have the power to initiate scrutiny against a person, which is from the start biased against the alleged “foreigner.” The stringent documentation requirements reflect an evidentiary standard reminiscent of criminal trials, but with a reversed burden of proof that disadvantages the person under scrutiny. Thus, the system has numerous hurdles, and failing even one of them can effectively diminish one’s status to statelessness. Contemplating statelessness is a terrifying prospect – it leads to the stripping away of rights to education, employment, healthcare, and legal due process. As in the case of the Rohingya, it also leads to arbitrary detention that can go on for years. Given that India has no bilateral agreements with Bangladesh – the alleged homeland for the “illegal” population residing in Assam – deportation is rarely carried out. The end outcome of the FT process is often detention in one of the six detention centers in the State, where detainees live in deplorable conditions. There is no distinction made between detainees and those imprisoned for crimes. They are not granted parole, and not allowed communication with their families. The detention centers are overcrowded and do not provide access to work, healthcare or recreation. In the event that the person is not detained, they exist in limbo, with no citizenship, and therefore no access to any rights.

The paper trail through which I put together Ruksana’s story ends with the signature and seal of the Tribunal on the 29th day of September 2018. I do not know what path she was forced to walk down on – was she able to approach the next step in the judicial ladder? Given that the High Court largely upholds FT verdicts, and requires access to significant resources, the sobering reality is that even if Ruksana took this route, it is highly unlikely that she found relief. Perhaps she joined the ranks of those detained, perhaps not. Be that as it may, she is now trapped in the state-woven web of statelessness, where she can only wait for an absolution that will likely never come.

In 2019, the government in Assam set up the National Register of Citizens (NRC). A documentary exercise to identify who belonged within the category of “citizen,” this register served to exclude nearly 2 million people from its ambit, people who now have to fight for their citizenship rights before the FTs. As Assam stands poised to begin this process of appeal, it is crucial that we understand how the system is biased from the outset against those who fall under the shadow of suspicion. There are talks of the government extending the NRC to the entire country, the consequences of which are likely to be disastrous for those who are most vulnerable. Now more than ever, there is a need for us to open our eyes to the reality of what this process entails for those who have to go through it. Ruksana and countless others stand to lose their “right to have rights.” We must find a way to bring their voices to the forefront lest our democracy lose its meaning for those who are most vulnerable to the whims of its judico-bureaucratic regime.