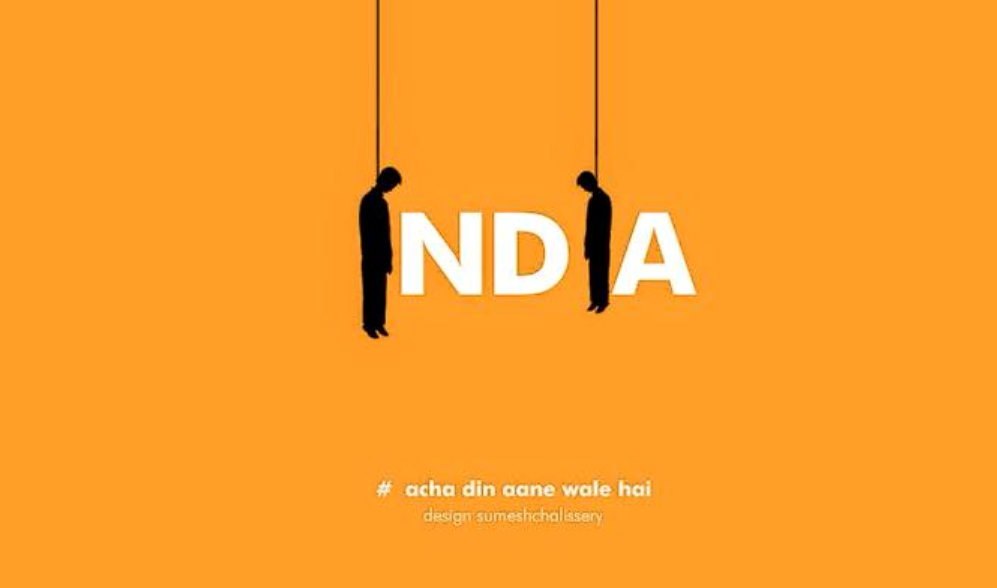

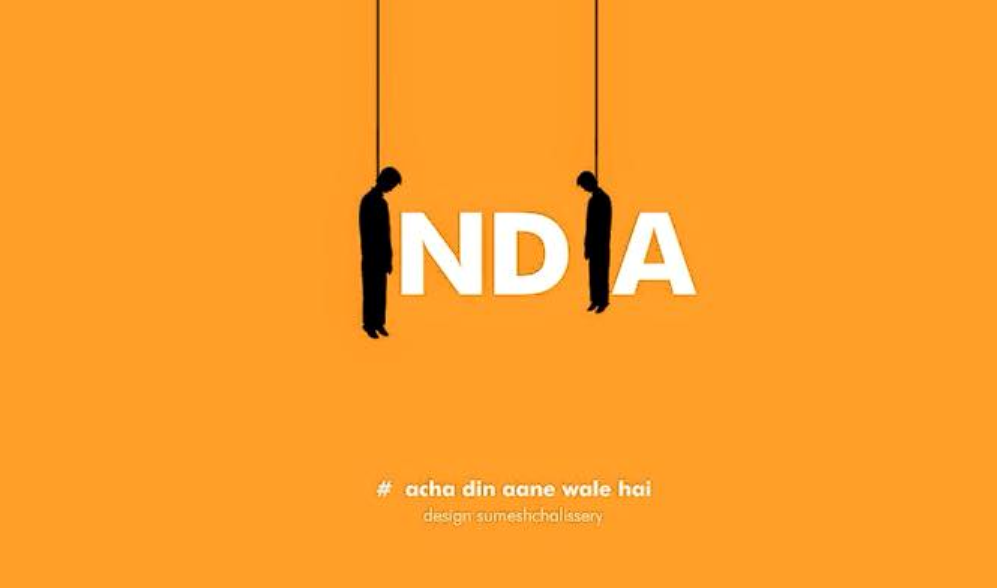

A lynching is a public, extrajudicial execution. Once we begin with this definition of lynching, the claim made in a recent Print.in article about a spate of WhatsApp rumor based lynchings that “There is, sadly, no political angle in these killings. There’s no Hindu-Muslim dispute, not even caste. There’s no India-Pakistan, no BJP-Congress, no jihad or Naxalism, no RSS or Kashmir, no statements and counter-statements by politicians”, stands in correction. Indian journalism and its reporting around lynchings have, oddly, focused on the medium as the messenger – WhatsApp – rather than the nature of violence, and its long history of targeting the ‘other’.

Acts of collective public violence do not occur in isolation. These seemingly independent events are linked to broader social, economic, and political forces. Framing these acts as “disciplinary violence” against an “errant” individual out of “righteous anger” or “anxiety” does great harm and disservice to understanding and preventing what is now an everyday enactment of grotesque violence.

For the past year, our team of researchers at The Polis Project’s Violence and Justice Lab has been building a data set on collective public violence and justice in India since 2000. Our dataset logs acts of mob-based violence – lynchings, massacres, riots, gang rapes, etc. involving two or more persons – and traces how these acts are processed through the justice system. We have found collective public violence to be steadily on the increase since 2000. This could be a function of better and faster reporting or a function of the availability of such information in non-traditional news spaces. However, what we are rapidly seeing through our data is that one cannot make either of the claims – that Indian society was ever tolerant, or, that violence has not been on the upswing.

India has always been a profoundly violent nation with a legal system that is skewed in favor of the country’s ruling elite. This is why perpetrators of such violence are often vindicated, while the most marginalized people and their bodies are the victims and sites of such violence. Recent repetitions of collective public violence against several types of victims, its recording and dissemination demonstrate that Indians have no fear of or faith in the institutions of the state to dispense justice.

“Lynchings were most common in regions with highly transient populations, scattered farms, few towns, and weak law enforcement – settings that fuelled insecurity and suspicion.”

The term “lynching” has often been traced back to William Lynch’s ‘Lynch Laws’ in an America driven by slavery as early as 1780. In 1782, Charles Lynch, a justice of the peace, is believed to have used the term to authorize extra-legal punishment of Loyalists. However, these assertions are the subject of much debate. A lynching is a product of a time with weak state penetration, where men and women frequently took the law into their own hands to punish those they thought had committed some wrongdoing. Often such lynchings in the American South between the 1880’s and 1920’s was carefully organized. Posters would be put up in advance, leaders of society and local notables like the clergy often attended these events. Photographs of the event were taken and sold as were souvenirs in the form of the murdered person’s bones, organs, and artefacts. Writing in the year 1900, Ida B Wells stated that “Lynchings were most common in regions with highly transient populations, scattered farms, few towns, and weak law enforcement – settings that fuelled insecurity and suspicion.”

In American lynchings were carefully planned. The lynchings of black people were socially produced events; they were manufactured for the explicit purpose of punishing black persons for perceived infractions, which in some cases could be something as small as insulting a plantation owner. In a time when the institution of slavery was abolished and African Americans began to be recognized as full human beings with rights guaranteed by the federal state, the act of lynching was an event of resistance against the will of the state. So the event of a lynching was not simply about punishment for someone, it was also a push back against the expansion of rights for persons that were deemed undeserving of those rights and freedoms.

Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith in Marion were lynched in Indiana in 1930. Local photographer Lawrence Beitler capitalized on the spectacle of lynching photographing the lifeless tortured bodies and grotesquely happy crowds. Lynching photos were made into postcards, with Beitler’s “Photographic Studios” name printed in the corner. The photo sold thousands of copies, that were printed by Beitler, who stayed up for ten days and nights printing. Beginning in the late 19th century, more than five thousand African Americans were killed by lynch mobs throughout America. In many white communities lynching was a public event, to be witnessed, recorded, made available by means of photographs and circulated as personal memorabilia. Here the photographs aided ritualized killing by dehumanizing the men and women brutalized by violence, while simultaneously normalizing and domesticating terror. They did not document or implicate an act of premeditated killing. Instead, they became personal mementos of a macabre carnival.

Lynchings destroy the notion of community, and, each act of violence renders the subsequent act of violence inevitable and more heinous. We should be worried about these events, and not relegate them to apolitical acts of disciplinary violence aimed at ‘alleged criminals’. Lynchings are predominantly discipline and punish project, directed at policing the other.’ A lynching, we argue, is always political. The collective public violence of mobs is almost always planned and is a joint criminal enterprise. To present such incidents as apolitical is to distort the political function that lynchings have performed. They are used as tools to threaten and police groups through a deliberate weaponization of civilians. Indian society is being primed to use violence as a solution for all social differences and conflicts. This is not surprising. In recent years, the ruling party, the BJP, has used directed and deliberate violence to polarize voters in specific constituencies. Where outright violence against the other has not been used, hate speech has been invoked as a proxy for actual violence.

Violence is executed through the indoctrination of hate that has been carefully nurtured as a part of a political project. Paul Brass’ work on Aligarh focuses on “organized riot machines” that manufacture Hindu-Muslim conflict. In this schematic, riots are produced and mob violence is premeditated to achieve particular ends. In these instances, there is proof of “preparation/rehearsal and activation/enactment.” This violence is seldom spontaneous and portraying it as such makes the pursuit of justice for victims harder, if not impossible. Lynchings destroy the notion of community, and, each act of violence renders the subsequent act of violence inevitable and more heinous. We should be worried about these events, and not relegate them to apolitical acts of disciplinary violence aimed at ‘alleged criminals’. Lynchings are predominantly discipline and punish project, directed at policing the other’.

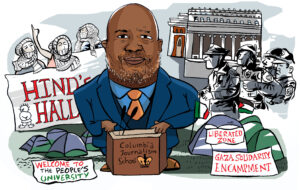

The WhatsApp Rumour Lynchings

In May 2017, a WhatsApp message doing the rounds in Jharkhand led to the death of 7 persons in two separate incidents in Jugsalai and Shobhapur. Three of the victims were non-tribal Hindus, while the other four were Muslim cattle traders. The rumor being spread was that a group of kidnappers was on the prowl looking for kids to abduct. Based on this, anyone that didn’t seem “native” to the place was under suspicion.

In 2018 there have been 22 such discrete and separate incidents across Indian states, resulting in 22 deaths. There were no deaths in 4 incidents, only injuries. But here is where things got really interesting and we began to see patterns.

In two of the four cases in Tamil Nadu, the victim was a non-Tamil speaker (a Hindi speaker). In fact, on the day of one of the lynchings, a mob had stopped a boy on a bike and let him go when he spoke to them in Tamil. So the mob was not looking for child kidnappers, but for an “outsider”. In the third and fourth incidents, the victims were a woman (Rukmani) that was suspected of being a child-lifter, and, a homeless man. Again, the victims were women or those without any power (the marginalized).

In Andhra Pradesh, 4 transgender persons were lynched resulting in one death. These victims were seen as the “other” or a sexual minority often viewed with derision and suspicion. In two of the three lynchings in Tripura, the victims were an unidentified woman and a street vendor from Uttar Pradesh, who was also Muslim. In the third Tripura case, the man that was lynched had been contracted to work for the government.

In the July 1 lynching in Maharashtra (Dhule), the five persons killed were beggars that were not known in the village. Again, these victims were poor. In the Madhya Pradesh (Singrauli) lynching, the victim was from an adjoining village and worked as an impersonation artist. He was a stranger in the village he was lynched in. In the Assam (Karbi Anglong) lynching, Nilotpal Das and Abhijit Nath were seen asserting that they were Assamese (natives), while the crowd did not believe this and murdered the two because they seemed to be “outsiders”.

In two of the three lynchings, we found in Odisha, the victims are one youth from Andhra Pradesh (outsider), and 7 youths from Tamil Nadu (outsiders). While no one died in these mob attacks, they came close to it. In the Gujarat (Vajad) lynching, beggar women in an auto were attacked. Here once more, the victims were economically and socially weak and one of them died.

While the identity of the victims vary, what unites them, in most of these cases, is their vulnerability and marginality. What can we make of these incidents? First, the victims are a category of people considered disposable. They are usually weak, poor, female, transgender, non-natives or outsiders (or suspected to be outsiders) and those that wield little power within their communities. While the identity of the victims vary, what unites them, in most of these cases, is their vulnerability and marginality. Second, the states in which a majority of these incidents have occurred (like Assam, Jharkhand, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Gujarat, Odisha) have had long-standing politics that have centered on either nativism, indigenous identity, and/or linguistic or religious nationalism, which have often led to anti-outsider sentiments, especially against migrant labor. Third, it is incorrect to state that there is no identity affiliation to these mob members or victims. From what we have found in these 22 incidents, there is definitely the pattern of the aggressors and victims not being the same in each case, but certainly being similarly placed in terms of social and political location in each state. This means that the aggressors in each case came from a majority of the local population (either a village or a neighborhood, or a shared tribal or linguistic identity). The victims, as we have stated above, also shared a loss of power in these settings.

Generating Judicial, Political and Moral Accountability

Lynching simultaneously enables erosion of civil behavior and creates a culture of impunity that makes further violence possible. It also removes the legal, political and social accountability from perpetrators and assigns them to a vague idea of mob exercising their spontaneous anxiety. We have previously analyzed witness testimonies from the Nuremberg, Yugoslavia and Rwanda trials, and have found clear roadmaps with perfected patterns of hate that lead to violence and destruction of a society. Some of these milestones include:

- The rules of criminal procedure are abandoned in favor of a trial by intentions and public opinion in which evidence is falsified, doctored and manipulated.

- Public shaming, humiliation, administering public mob justice, painful corporal punishment in public, and forcing a group of people to wear identifiable markers.

- Democratic culture (the rule of law, due process, protection of minorities, and social justice) is considered as being ancillary to state power and its interest.

Lynching simultaneously enables erosion of civil behavior and creates a culture of impunity that makes further violence possible. It also removes the legal, political and social accountability from perpetrators and assigns them to a vague idea of mob exercising their spontaneous anxiety. The language used to describe these lynchings in India has outsourced responsibility for these murders to rumors embedded in WhatsApp forwards. Such apportioning of the blame on technology and social media is an abrogation of political and social responsibility. India certainly has a problem of collective violence, but it also has a problem of foundational violence – the roots of collective public violence that we are witnessing today have roots in a profoundly unequal society made more violent by hate nurtured along religion and caste.

Rumor as a mobilizing agent in race riots, and, communal, ethnic, and caste-based violence has been amply studied. Again these rumors are not spontaneous utterances, but often carry with them the authority of acceptable prejudices. Rumors, forwarded and spread, are weapons of political hate, with a long documented history. For instance, a study by PUCL in 2002 found that two vernacular newspapers – in particular, Gujarat Samachar and Sandesh – ran false stories, fabricated sensational headlines with the intention to “provoke, communalize and terrorize people”, which incited and encouraged Hindus to kill Muslims. WhatsApp rumors are not new; what is perhaps new is the manner in which the news is distributed, and speed of their virality. Even in the pre-mobile phone world, genocidal violence in Rwanda and Bosnia were made possible through rumors.

The generation of accountability and justice in this scenario is difficult to think of but not impossible to accomplish. Whatever we have on lynchings in the public sphere are commentaries that act like endless laments. Our first challenge as a society is to stop this current spate of lynchings and protect future victims of such acts. This violence against Dalits, women, religious and sexual minorities, and the poor should not be seen as new: It is a part of the violence that these communities have repeatedly faced over time. The real reason that these persons are overwhelmingly the victims of recent lynchings is because of who they are. The WhatsApp rumors are just the latest reason to revisit historical violence on them.

We as a society need to break out of these cycles of endless violence if we are to survive first as a humane society and then as a republic. The first step in that direction is to see the violence for what it is – a re-enactment of historical distrust, animosity, and prejudice against weaker groups. The second step is to prevail upon the political establishment to accept part of the guilt for these deaths. After all, it is the politicians that have been pushing forward agendas that divide populations on whatever the latest ethnic schema is – native versus outsider, Hindu versus Muslim, tribal versus non-tribal, men versus women, rich versus the poor, and so on. Third, is to let the political establishment know that the politics of division will not lead to electoral payoffs. These payoffs are the only reason parties still indulge in divisive behavior. Fourth, the mechanism of justice must be swift and ruthless in apportioning responsibility for mob murder. This would mean some burden on the police system, but mob violence has low conviction rates because it is extremely difficult to forensically lay guilt on large numbers of people. However, there is ample evidence from videos and photographs that can be harnessed to bring the guilty to justice. Finally, the public pursuit of institutional justice for these victims should be collective and relentless.