This essay critically engages with Italian philosopher Agamben’s reflections on “naked life” in relation to the state of exception instituted to counter COVID-19. This state of exception is a “new” paradigm of rule where the threat of virus-as-terror trumps mere biological survival over moral, social relations. Future politics is likely to accentuate in the confluence of biopolitics and friend/foe pairing.

Busy in unmasking power until recently, now many seem to have become fans of masking in the wake of exceptional measures undertaken by various governments to tackle coronavirus (COVID-19). I use masking as shorthand for some animated responses to the critical notes [1] Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben published regarding the outcome of such government measures. These measures include(ed), among others: ban on the freedom of movement; closure of public spaces such as parks, train stations, airports, museums; shutting down institutions like schools, colleges or universities; prohibition on any gathering – social, cultural or political; and strict observance of social distancing in places where people are permitted to visit. Agamben was subjected to severe but unfair criticism.[2]Contra his critics, I argue how Agamben’s reflections are fundamental to understand the political effect of our fear-ridden global present and future.

This essay examines two core issues resulting from a variety of measures undertaken by different states across the world to deal with coronavirus. First, it analyzes the emergence of what Agamben calls “naked life” concurrent with COVID-19. Unlike naked life in the Nazi extermination camps established away from the “normal” social habitation and discussed in Home Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life (1998), Agamben now marks the onset of naked life right in our midst and as a consequence of the exceptional measures to counter the pandemic. Second, it dwells on the state of exception instituted in the wake of the “battle” or “war” against the virus. Here I discuss the politics of enmity evident, inter alia, in militarization, vilification, scapegoating – in the name of ethnic or religious communities and nationalities – and its intricate relations with democracy and the media.

What is Naked Life vis-à-vis Democracy?

At the center of Agamben’s reflections is how the array of measures adopted by the governments against the coronavirus has reduced humans squarely to cling to mere “naked life,” leading thereby to the near abolition (or reorientation) of all that is social and humane. The naked life is “bare life,” a concept theorized in Agamben’s Homo Sacer. The last two words in the subtitle are English translations of the original Italian nuda vita. Unlike that of Homo Sacer, the translators of Means Without End: Notes on Politics (2000), another important book by Agamben, render it as “naked life.” The concept of naked life stems from a distinction in Greek between zoē and bios. While zoē refers to life characteristic of all living beings, animals included, bios symbolizes a collective, qualified life in a polis. That is, in the ancient Greek world zoē was mere biological life whereas bios pertained to life in a political community. The power of Agamben’s argument lies in the sheer force with which he shows how the neat separation between the domain of natural (naked) life and the arena of political life has blurred to pass into “a zone of irreducible indistinction” (p. 9). To Agamben, the figure of the Jew in the extermination camp analogized as “der Muselmann” (the Muslim) is the paradigm of naked life – life robbed of political status and denuded of any protocol of citizenship. Paradoxical though it may appear at first, this life is part of the very community from which it has been set apart as a matter of exception. Which is to say that “the rule applies to the exception” in its withdrawal as opposed to its application (p. 18). Put differently, by re-inscribing bios into zoē, the sovereign power that be decides which life to dispense with and which life to let live or protect. In Agamben’s analysis, the camp becomes possible in a state of exception presided over by the sovereign. But as he argues in Means Without End, the state of exception has lost its exceptionality to become almost a norm.

It is worth pointing out here the radical implication of Agamben’s argument about the uncritical celebration, if not deification, of democracy. The Nazi extermination camp was not simply one bad event or moment, but the very exemplification of modernity and its biopolitics. Agamben indeed speaks of “an inner solidarity between democracy and totalitarianism” (Homo Sacer, p. 10) well after the end of the Second World War. He even goes to the extent of saying that “Western politics is a biopolitics from the very beginning” (ibid. p. 181). The distinction of Agamben’s thought in Homo Sacer comes to its full glare in comparison with Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History and the Last Man (1992), both written in the aftermath of the collapse of the former Soviet Union. In radical contrast to Fukuyama’s excitement about what he viewed as the victory of liberal democracy over communism, Agamben was deeply critical, even distrustful, of liberal democracy.

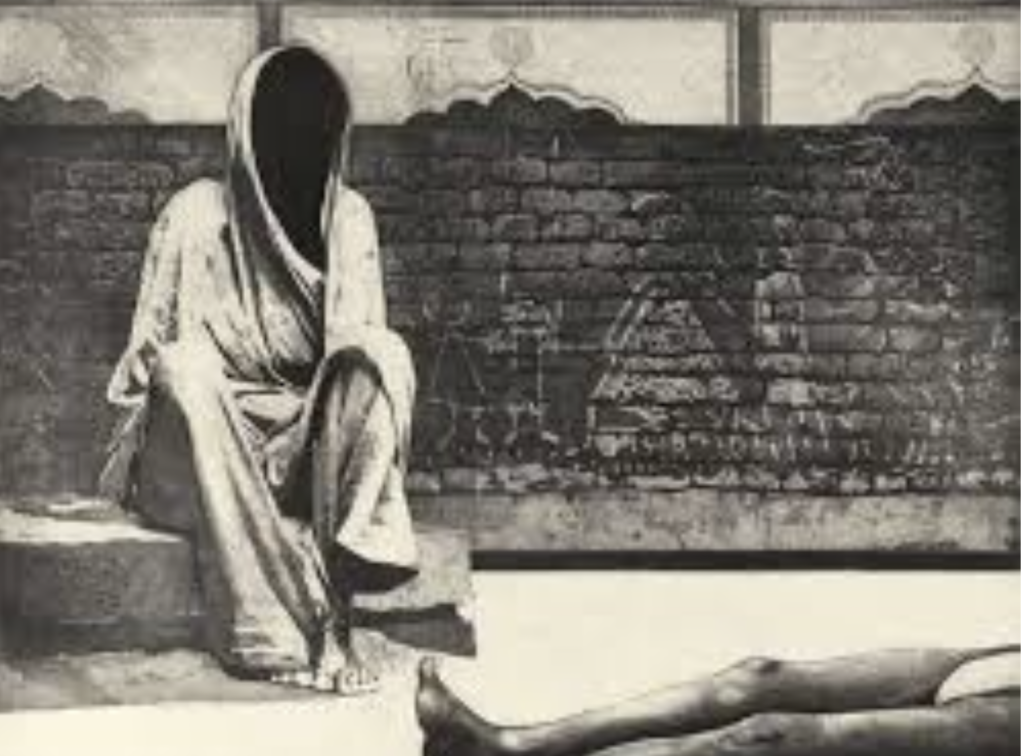

To return to what Agamben thinks is the diminution of human life (bios) to mere naked life (zoē) after the state of exception introduced to deal with the coronavirus, its resemblance with the camp is discernable in many ways. The simile is not in the sense that naked life post-coronavirus is prone to extermination in the same way as it was in the camp. The resemblance lies instead in the tearing apart of collective life in a community characterized by solidarity based on sociability. In this way bios gets reduced to zoē and the preoccupation with the latter singularly triumphs over the former. This concern with the social dimension as an ideal of one’s relationship with the polis is reflected most in Agamben’s anxiety about the disposition of the living toward the dead and the dying. It logically follows that there is simultaneity between the reduction of human beings to mere naked life and the state of exception various states have instituted. As discussed below, the most serious –probably, also the most terrifying – example of the naked life that Agamben gives is the abandoning of the sick by the healthy and of the dead by the living, the latter manifest in corpses simply burnt without even a funeral in its minimalist sense. The ground for this state of exception, Agamben further observes, is the new pandemic. By this, he means that the threat of terrorism, which had led to a state of exception in Western democracies (and elsewhere) since 9/11, now seems to have exhausted itself as a cause. Such a markedly political analysis by Agamben became contentious for his many critics, who accused him, inter alia, of living in a fancied world.[3]

Reality in Relation to Truth

Concerned as he squarely is with human relations in everyday life, Agamben is not dismissive of the “reality” of coronavirus. He made it clear in a set of “clarifications”[4] and “a question”[5] published respectively on 17 March and 15 April as a sequel to his first reflections on 26 February 2020. Agamben is interested in the series of measures taken by the states to deal with the virus and the ways in which they are radically transforming our very sense of who we are and how we, as human beings, relate to one another. Agamben’s prime contention, then, is how humans stand reduced to “naked life,” struggling thereby for the upkeep of their naked biological rather than humane social survival as an ideal polis would have it. Further, this reduction to “naked life” is linked to measures adopted by the states and power elites while claiming in the same breath to “save” the people in whose very name the extraordinary measures are/were taken, and the state of exception instituted across the nation-states. For instance, the federal government of India hurriedly announced the lockdown giving people no more than four hours’ notice before its enforcement. In imposing the lockdown, the federal government did not consult even the state governments, let alone the public. The continuing plight of the multitude of the migrant poor in various cities and violence inflicted upon them is the ultimate insignia of the fact that they were barely of concern to the government, which proclaimed the lockdown out of a blue.

Here Comes Naked Life

Agamben offers crucial insights into the radical transformation of social relationship resulting from the states’ unprecedented measures against the coronavirus. These measures have already altered – and will likely do so more – what it means to be human. Instructively, Agamben speaks of humans reduced to “naked life” such that bare biological survival has trumped everything else. Rather than bind us together, Agamben further muses, the fear of death or losing what is already a naked life “blinds and separates” humans. Central to Agamben’s analysis is a profound moral question that he raises in “clarification” published on 17 March: “What is a society with no other value other than survival?”

Reflecting on the dead, he observes that they “have no right to a funeral and it’s not clear what happens to the corpses of our loved ones.” So fundamental is this concern with the dead that Agamben underlines it in his subsequent thoughts published on 17 March as well as on 15 April. Since to escape the viral contagion and risks to health, relational proximity is sacrificed to follow the new rule of social distancing, he asks: “How could we have accepted […] that persons who are dear to us and human beings in general should not only die alone, but […] that their cadavers should be burned without a funeral?” This practice – burning the cadavers without a funeral – he claims, “had never happened before in history.” In this context, he is particularly critical of the Catholic Church, which has maintained a silence over it. It has also abandoned, Agamben writes as if to reminds us, the spiritual message that one of the most virtuous acts is to visit and attend to the sick.

On 6 April 2020, a Hindu woman died in Indore, a city in the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh. Fear of being infected with the virus prevented her relatives and Hindu neighbors from cremating her. It is such moral retreat, if not outright cowardice, as manifest in the (in)disposition of the living towards the dead that is a fundamental concern of Agamben. Carrying the dead on their bare shoulders for over two kilometers and enacting moral courage, Muslim neighbors later undertook her cremation.

Since Agamben’s analytical attention is placed on states’ measures, a pertinent question is: what about the disposition of the heads of states toward the dead? For the British Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, the living seemed already dead and hence he did not consider it worthy to address the dying. He instead asked Britons to prepare “to lose loved ones.” What morality is at play here when an elected leader selects not to address the very dying people who, or at least some of them, had elected him?

Equally significant are depiction of coronavirus as an enemy and the regnant idiom of warfare in which Boris Johnson, Donald Trump and others, including India’s Narendra Modi speak. Modi remarked that “this war” against coronavirus would take three more days than the Mahabharata war that had taken eighteen days to win. The war Modi referred to figures in the Hindu epics as a war for a throne.

Militarization, Demonization and the State of Exception

The war against coronavirus in India is in many significant ways a war waged against Muslims. News media began to spin the narrative that Muslims were willfully spreading the virus. “CoronaJihad” and “Muslim means terrorist” trended on Twitter. The official discourse only legitimized this narrative that the coronavirus curve was fine until Tablighi Jamaat (TJ), a non-political organization persuading Muslims to practice religious rituals (especially, daily five prayers), radically changed it. The Times of India, one of the most read newspapers in the country, linked TJ with terrorism.

Likening coronavirus with terrorism, M.P. Renukacharya, a lawmaker from the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), issued a call “to shoot them with a bullet.” By “them,” Renukacharya meant the TJ followers, who had been fearful of undergoing medical tests as a result of the stigmatization of the disease in general and the mass vilification of Muslims as deliberate spreaders of the virus in particular. Baseless rumors branded Muslims as “coronavirus terrorists,” accusing them “of spitting in food and infecting water supplies with the virus.” One BJP leader likened the TJ members to suicide bombers. I watched him say this on Deutsche Welle (DW), Germany’s international broadcaster, in its English news bulletin live streamed on 18 April at noon. One Youtuber in the southern state of Tamil Nadu also described the TJ followers as suicide bombers. On 2 April, Maridhas uploaded a video titled: “Maridhas answers: Terrorism + Corona = India’s new problem| Tablighi Jamaat Issue.”

Clearly, my point is not that some cases of coronavirus spread are not linked to TJ at whose headquarters in New Delhi hundreds of people stayed. Rather, my point is the political demonization of The Muslim as an enemy deliberately spreading the virus among Hindus. Manufacturing and weaponizing this narrative requires eliminating mention of similar gatherings by Hindus, Sikhs and other. No less significant is the choice of markedly different words deployed by the media in describing Muslims and Hindus in similar conditions after the announcement of the lockdown by the government. As linguist Rizwan Ahmad aptly observes, while Muslims were depicted as “hiding” in their religious places, Hindus and others were simply “stuck” or “stranded.” It is also worth noting that until 23 March India’s Parliament continued to function. And as late as on 2 April, chanting “Jai Sri Ram (hail Lord Rama),” thousands of Hindus thronged to temples in West Bengal. Disobeying the lockdown and social distancing, the Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister, Yogi Adityanath, himself participated in a Hindu ritual with more than hundred and fifty people.

The Indian example demonstrates the striking confluence between biopolitics of Foucault and the definition of politics as friend-enemy dualism by Carl Schmitt – theorists Agamben engages with. As explained below, unlike Agamben, I see a confluence between biopolitics and friend-enemy dualism rather than the replacement of the latter by the former as he seems to suggest. Notably, in his first critical notes (see footnote 1), Agamben wrote about society’s “militarization” simultaneous with states’ exceptional measures against coronavirus. This militarization was already underway. Accompanied by the Police, Ajit Doval, India’s National Security Advisor tasked with advising the Prime Minister on internal and external threats to the nation, visited the TJ headquarters to “evacuate” its residents. That Muslims are the singular biopolitical-terror threats is evident from the fact that Doval did not visit any similar places belonging to other communities. What is more, in its bulletin about the coronavirus cases, the Delhi government has a separate column called “Markaz Masjid [the headquarters mosque].” The mention of mosque as a separate category in the government bulletin is as political-inimical as is the column itself. This religious demonization has resulted on an attack against a mosque in Delhi, the prevention of Muslims’ entry into Hindu areas as well as the deadly assault on Mahboob Ali, a Muslim accused of planning to spread coronavirus (even as Ali had not tested positive).

Disciplining and attacking stigmatized populations on the basis of culture, religion or nationality – recall that Trump initially called coronavirus the “Chinese virus” and later defended the use of that phrase – and their alleged links to the disease have occurred in many places. The state of exception Agamben spoke about is in front of us all. In the name of fighting coronavirus, Viktor Orban in Hungary has become a dictator to rule by decree until he deems it fit. Shades of state of exception are also evident in Ghana and Sri Lanka. Surveillance by the states and companies and crackdown on journalists and activists have intensified in Bangladesh, India and Kenya. In India, those arrested include two research scholars from Jamia Millia Islamia, a central university in New Delhi. The “bogus” charge against these scholars – Meeran Haider and Safoora Zargar – is that they instigated political violence or pogrom in Delhi in February 2020.

In Jammu and Kashmir, where a state of emergency has been in place for quite some time, many journalists, including Gowhar Geelani and Masrat Zahra, have been arrested right during the country-wide lockdown. These arrests have been made to justify the state’s fight against “terrorism.” Geelani is not an ordinary journalist. He is the author of Kashmir: Rage and Reason; a Chevening fellow in 2015, he had earlier worked as an editor at Deutsche Welle. The 26-year old Zahra is also a well-known photojournalist whose work has appeared in Al Jazeera, The Caravan, The New Humanitarian, TRT World, and The Washington Post. To clarify, my point is not that pandemic alone has led to the state of exception (or intensified where it was already in force) and massive crackdown on journalists and activists.

Has Coronavirus Replaced the Earlier Enemy?

As in India, cohabitation of Islamophobia and counter-coronavirus measures are visible in other countries too. Responding to Agamben, Sergio Benvenuto, an Italian psychoanalyst, wrote how his domestic worker was certain that Arabs-Muslims “schemed” the coronavirus. In Britain, far-right groups blame Muslims for its spread. Across the Atlantic, Gregory Gutfeld, an American television producer, urged his viewers “to think about this [coronavirus] the same way we think about terrorism and 9/11.” The US Justice Department has declared that anyone intentionally spreading the virus would be charged under terrorism laws.

This declaration – identifying as it does the virus with terrorism – emanates smoothly from the repertoire of the Global War on Terror (GWOT) when George Bush Jr. expanded the ambit of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) to include “any explosive incendiary, or poison gas, bomb, grenade, or rocket having a propellant charge of more than four ounces” and “any weapon involving a disease organism.”[6] Anthropologist Joseph Masco perceptively observes the fusion between “infectious disease” and the expansive ambit of WMD at the heart of GWOT. Such definitional measures were rationalized to counter “bioterror” and achieve biosecurity. Like the ambit of WMD, that of biosecurity too, originally used to protect sheep from infectious disease in the antipode in the 1990s, was given an almost infinite expanse to include preemptive war on terrorism.

In her response to his critical notes (see footnote 3), Anastasia Berg seems outraged at Agamben’s suggestion that “with terrorism exhausted as a cause for exceptional measures, the invention of an epidemic offered the ideal pretext” for expanding the state of exception. I too disagree with Agamben, though for an opposite reason. Agamben’s assumption of replacement of the old enemy by a new one – of terrorism by coronavirus – seems somewhat rushed. He also seems to bypass the connections between infectious disease and terrorism already in place. Masco writes about the transformation of the US from counter-communism to counter-terror security state, which, after 9/11, packaged “the infectious disease as a form of terrorism.” Likewise, by placing virus in the category of potential biological weapon, it branded the “yearly flu […] into a form of terror” (p. 152). In contrast to Agamben, I have shown in this essay that there is already an overlap between the virus and terrorism, which Agamben takes respectively as new and old enemy.

My analysis also serves as an immanent critique of Agamben on another point. Contra Agamben, who in Homo Sacerargues that naked life/political existence (zoē/ bios) rather than friend/enemy is “the fundamental categorial pair” (p. 8) of politics, the data this essay is based on demonstrate that they both exist side-by-side as co-constitutive. Vilification of Muslims as an enemy is present even in those initiatives that apparently aim to counter it. Recall the vilification of Muslims by the Indian media and part of the government as planned spreaders of coronavirus. According to this vilification story, Muslim vegetable hawkers spit on vegetables and washed them in gutter water. A short film titled Darr (Fear) helped spreading this politics of enmity in the garb of delivering a message of “harmony between communities” and protecting “national unity.”[7]

The seven-and a half minute film shows Osman, a Muslim vegetable hawker –in green shirt and white skullcap – knocking on the door of one Sharma, literally begging him to buy vegetables from him. In the background is the television news about coronavirus in Sharma’s posh living room. Shown in a T-shirt with the US flag and Abraham Lincoln’s photo on it, Sharma refuses to buy from Osman saying he had already placed the order for vegetables online. As a disappointed Osman leaves Sharma’s flat (the main gate of which is marked with visible Hindu symbols), he meets Ramcharan, a Hindu vegetable hawker. Ramcharan, who is in fact carrying a bag of vegetables for Sharma, tells Osman that Sharma refused to buy from him because of the pervasive fear that Muslims hawkers spit on vegetables. He also tells Osman that though only a few Muslims do this, yet the entire community gets negatively tarnished. Rather than contesting the very fictitious basis of the vilification and politics it partakes in, the film legitimizes both in the disingenuous language of ratio: not every Muslim vegetable hawker, but only some spread the coronavirus by spitting on vegetables. Notice how fiction is magically transformed into facts and the deadly politics of enmity mass staged in the guise of “harmony.” For some readers it might matter to know that the names of all actors as they appear on the screen are Hindu.

The long future will tell us to what extent Agamben is right and whether his observations are productive. The state of exception and politics of enmity constitutive of liberal democracies around the world, I fear, will intensify. I hope I am wrong.

[1]Giorgio Agamben, “The Invention of an Epidemic” https://www.journal-psychoanalysis.eu/coronavirus-and-philosophers/; originally published in Italian on Quodlibet, https://www.quodlibet.it/giorgio-agamben-l-invenzione-di-un-epidemia)

[2] Many responses to Agamben’s remarks are available under the title of “Coronavirus and Philosophers” at https://www.journal-psychoanalysis.eu/coronavirus-and-philosophers/

[3] Anastasia Berg, “The Italian Philosopher’s Interventions are Symptomatic of Theory’s Collapse into Paranoia.” 30 March (https://www.chronicle.com/article/Giorgio-Agamben-s/248306 ), Jean-Luc Nancy, “Viral Exception.” (https://www.journal-psychoanalysis.eu/coronavirus-and-philosophers/) , and Slavoj Žižek, “Monitor and Punish? Yes, Please (http://thephilosophicalsalon.com/monitor-and-punish-yes-please/) take, though differently, Agamben as defying, if not denying, reality.

[4] Giorgio Agamben, “Clarifications” https://www.journal-psychoanalysis.eu/coronavirus-and-philosophers/

[5] Giorgio Agamben, “A Question,” (translated by Adam Kotsko) https://itself.blog/2020/04/15/giorgio-agamben-a-question/

[6] Joseph Masco, The Theater of Operations: National Security Affect from the Cold War to the War on Terror, Duke University Press: 2014, p. 39; italics added.

[7] The film is presented by Studio 32B, written by K.K. Shukla, directed by Raghav Tripathi, produced by Raghav Karkhana Production and shared on Facebook on 3 May.