Of Worlds Within Worlds: Travelling Through 65 Years of Gulammohammed Sheikh’s Outstanding Oeuvre

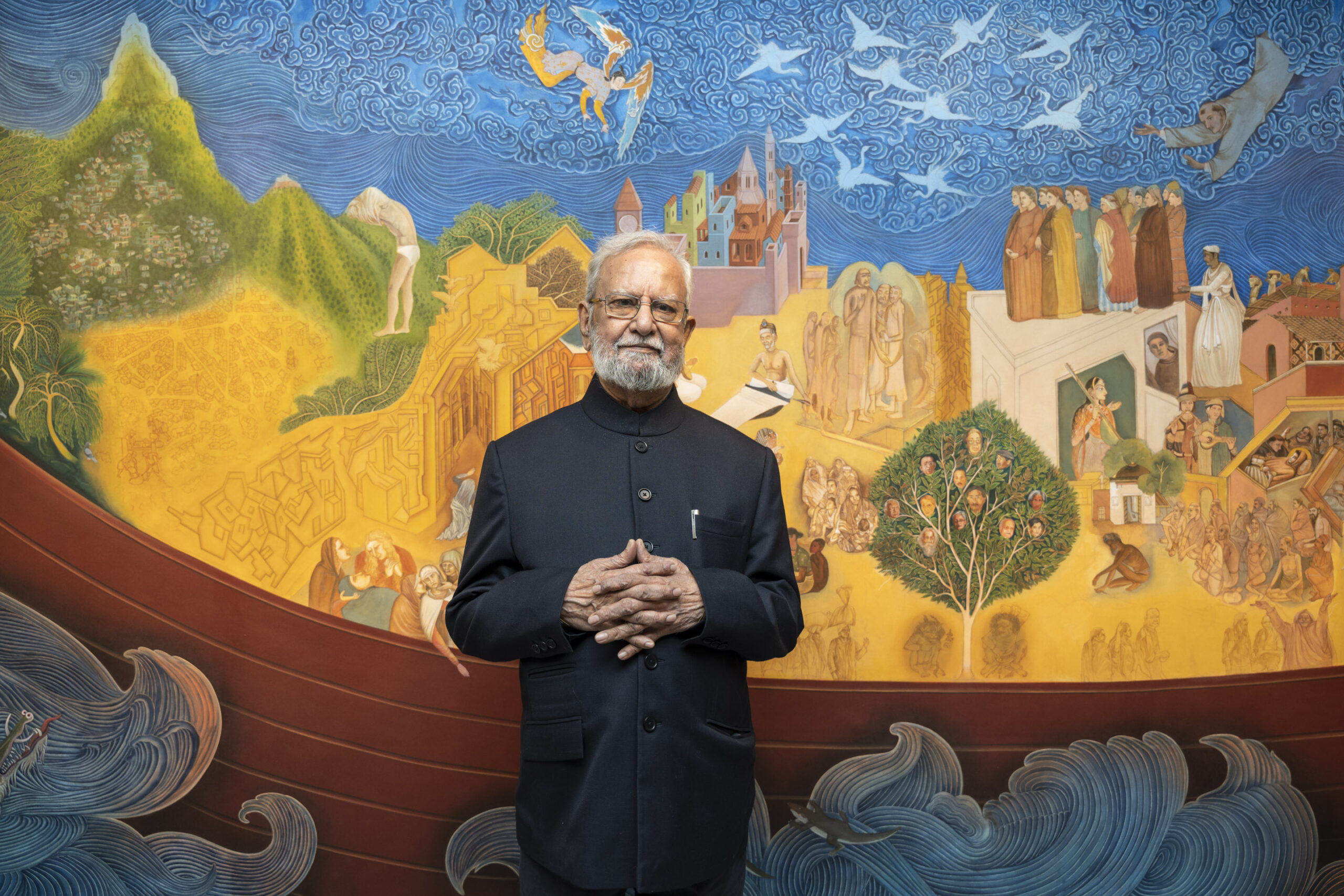

Sounds clatter, crack, and claw out of the works of the Baroda-based painter, poet, and pedagogue Gulammohammed Sheikh. This 88-year-old artist’s multidisciplinary body of work buzzes with the insights, illuminating our collective memories—lived, imagined, and remembered—keeping them pulsing like a raw, open wound. His quietly radical acts over six decades thrum together timelines, coaxing each generation into witnessing the multiple truths that go into building our worlds.

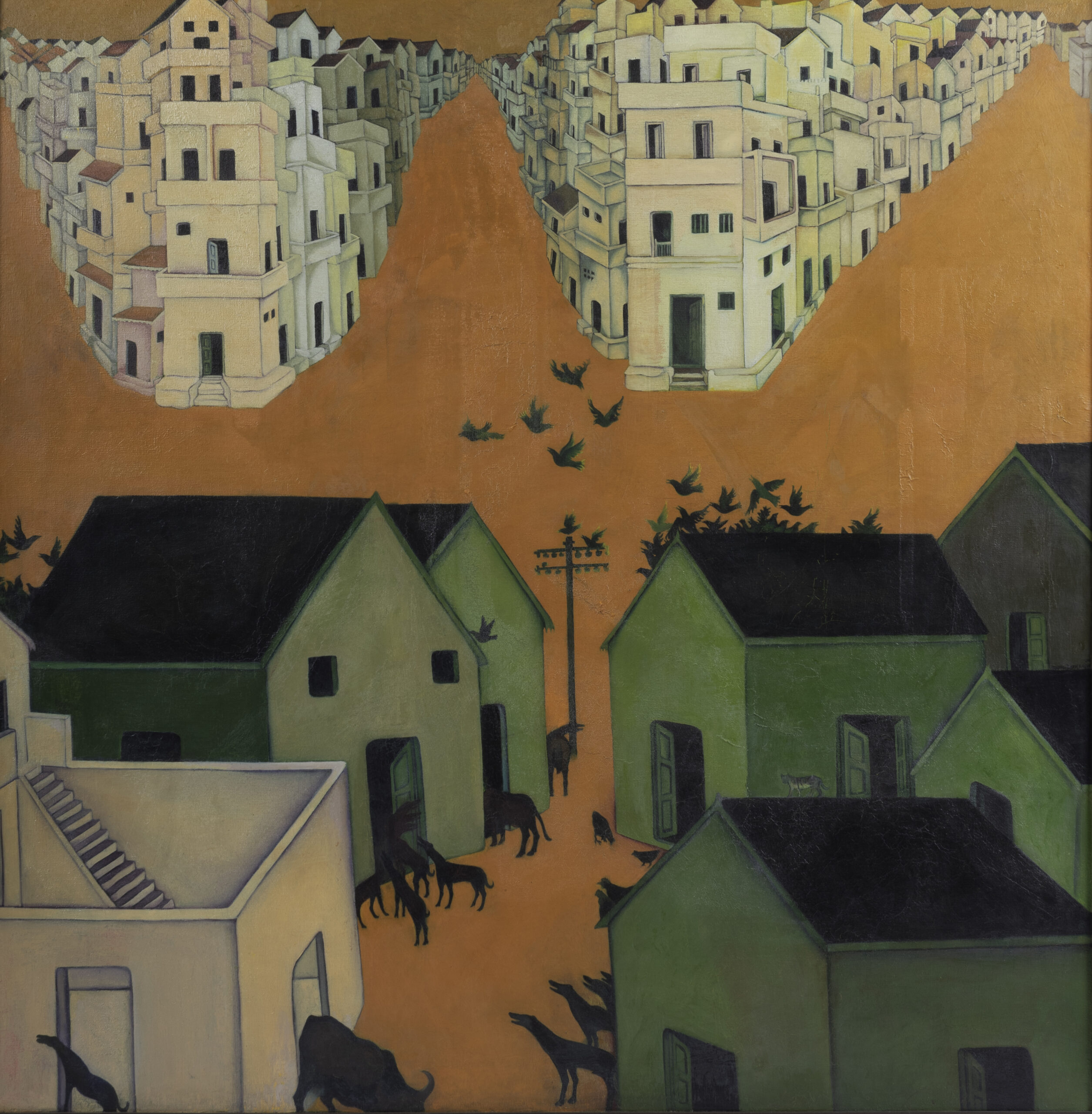

Sheikh’s oil-on-canvas painting from 1975, Speechless City, trembles and terrifies with its howling dogs, cawing crows, and whistling wind. There are two cities in this painting: the first, a grounded city with its familiar houses—sloping tiled roofs, green walls, windows and doors thrown open, lights off, grouped yet deserted except for the pack of shadowy hounds and a lone bull.

The second inverted, ghostly, multi-storied, more foreign city floats in the orange sky, receding into the distance, its front-facing building reminiscent of New York’s Flatiron Building. A murder of crows ominously blot the sky between them. While the imagery itself is stark, the sight and sounds of these creatures are horrifying, haunting—a callback to funeral grounds—and fill all the space in the painting.

These melancholic sounds rattled through my body as I took in the remaining 189 works at the Gulammohammed Sheikh retrospective—Of Worlds Within Worlds—at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art in Delhi. Curated by Roobina Karode, the director of the Museum, who has a 50-year-long familiarity with Sheikh’s work as she was his student at The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda.

Karode brings a thoughtfulness to the exhibition, balancing Sheikh’s panoramic works with his personal pursuits and paraphernalia. Through the museum’s dimly lit galleries, we get a thrilling opportunity to travel through 65 years of Sheikh’s outstanding oeuvre, from his formative years in Baroda in the 1960s to his most recent excitement with the digital medium.

As Karode writes, “collaging histories and collapsing time, Sheikh zooms in and out of the surface, his compositions almost kaleidoscopic.” We witness his ability to blend, bend, and imbue these works with themes that speak to communal violence and religious bigotry, the clash between mythologies, histories, and modernities, the devouring of the village by the hyper-efficient city, and our growing distance from our own nation’s truths.

Through many-splendoured forms—like gouaches, oil paintings, pen and ink drawings, graphic prints, digital collages, accordion books, poems, photographs, ceramic objects, large-scale structures, and installations—Sheikh lets these ideas guide the storytelling. His gift, his legacy, is a scalpel-like eye that opens out worlds within worlds, and this glorious retrospective pins down this sensation perfectly.

Speechless City was Sheikh’s fiery, painterly response to the Emergency (1975-77), a period of clampdown on basic democratic rights. Its constitutionally transgressive events are always spoken about in the past tense as if the nation has collectively forgotten to recognise that it has been repeating itself. Sheikh’s painting is a sharp, sonic reminder of the result of continued silence.

Sheikh is truly a master of guiding sound into his works; on occasion, it can be pleasant, too. Returning Home After a Long Absence (1969-73, oil on canvas) has a sweeter sound bustling through its tightly-packed, brightly-coloured houses and Chinar trees—seemingly transplanted from Mughal miniatures—within a walled enclave.

Pause for more than a moment in front of this painting, and one can even hear the beautiful azan emerge from the gem blue mosque glowing in the centre of the mohalla (neighborhood). Winged men, including the faceless Prophet on a buraq, a winged horse—figures from the Islamic tradition—flutter and dance through the thickly applied, inky blue sky.

In the foreground is a portrait of Sheikh’s mother based on a photograph, locating the painting in his hometown of Surendranagar in Gujarat. The sounds emanating from this painting are soothing but still stirring, tinged with the painter’s nostalgia for home. This painting also marks a significant shift in Sheikh’s style, where he began merging his many ideas, different timelines, the possible and the pliable, together within the same frame.

In another series of paintings, light—one of the instruments in a painter’s kit—becomes another voice in his chorus. In a series of ‘yellow landscapes’, different shades of yellow wash over gnarly trees, lone dogs, towering buildings, and pondering people like sunshine drowning everything it touches. The scenes feel warm, sweltering, and sweaty, but also like the entire world has stopped to take a deep breath.

In one of the sweetest paintings in the exhibition, We Two (1970, oil on canvas), blue-green trees with cloudy canopies and veiny branches stand tall atop rolling meadows. A spectral buraq gallops in the sliver of sky. Against a butter yellow background, Sheikh and his wife, the formidable artist Nilima Sheikh, are painted within a walled enclosure. This painting radiates with the warmth of the painter having found his home alongside his favourite person. While light dances and dominates this set, there’s the whisper of a breeze here too, the gentle gurgle of a stream, the hushed rustling of leaves thrumming through these paintings.

In another painting, Sheikh turns off all of the lights, drains out the bright, saturated colours, and mutes the sound. In Ahmedabad: The City Gandhi Left Behind (2015-2016, casein and pigment on canvas), one is given a bird’s eye view of a burnt and charred city expressed in subtly varying shades of black and grey. It is a frightening visual of the aftermath of the many communal riots in Gujarat.

There’s also a fiery patch of a burning autorickshaw blazing within the painting’s frame; searching through the murky gloom of the dark painting, thirsty for more details, one might come across a pair of sandals, pocket watch, plate, bowl and the round spectacles—five personal objects of daily use which were markers of Gandhi’s simplicity—randomly tucked into the huddled clusters of mohallas that form the heart of Ahmedabad.

As one adjusts to the darkness in Ahmedabad: The City Gandhi Left Behind, suddenly lone figures appear. They potter around the abandoned streets carrying on with their daily rituals, beacons of resilience and revolution in the aftermath of great violence. Just when it gets too dire, too much, a bright blue patch magically emerges, allowing for a breath.

Within this rectangle of light, a lone auto rickshaw rides on a street lined with buildings. Is it this auto rickshaw that was set on fire in the riots? Or is it a peek into a hopeful future where the city returns to normal once again?

One never seems quite sure; Sheikh’s technique of collaging within his paintings plays with this tension between timelines. His paintings side-step providing resolutions. Instead, they are layered with his memories, his wealth of reading, listening, seeing, feeling, and touching the worlds around him. In making this choice to open himself and his worlds to us, he nudges us to find our own universes within.

Sheikh’s brilliance isn’t the mastery of many techniques alone, which on its own would be more than enough. It’s his genius to push the parameters of painting, to allow for his metaphors, his quotations, to be still and also spill out of the frame. He corrals the mythic and historical, the mundane and magical, the high-brow and low-brow within the expanse of the canvas.

These influences rub shoulders with each other, might ignore one another, or one might knock knees with another. These encounters, these frictions allow for the past, the present, and the possible to dance together; occasionally one takes the lead, they cleave together, and they cleave away. Sheikh’s paintings are personal, political, and burst forth from being a good reader, listener, and observer of his life so far.

Works like Kaavad: Travelling Shrine: Home (2008, boards mounted on a steel structure, digital print on paper and vinyl) and his other smaller renderings of the kaavad, a traditional travelling wooden shrine or storytelling device from Rajasthan, are a physical manifestation of the hold of Sheikh’s work has on us, the viewer. Swallowed into this larger-than-life work, we’re one among his iconic figures from our collective stories and histories, travellers and characters in this work too.

Listen for a hair’s breadth even and you’ll hear the musical instruments, the swirling of the winds, the songs of Kabir, the poems of Tagore, and even the tiny emerald-green fish plopping in and out of the all-consuming waters.

Sheikh has demonstrated profound care from his earliest works, giving every little detail close attention. His first set of paintings from the 1960s employed the motif of horses, their tongas, and crowded cities. These poor, emaciated creatures that are usually ignored catch Sheikh’s eye. He doesn’t need them to be grand or galloping or manes flying in the wind; he needs them just to be in the world. In turn, he allows us to see them in our worlds too—and they are lovely.

And in his latest, Kaarawaan (2019-2023; acrylic on canvas)—which spans across an entire gallery’s wall of the museum—Sheikh brings together all his favourite people, places, and things on a gigantic boat. Artists, philosophers, creatures, writers, trees, and mountains, motifs and techniques from the Mughal, Renaissance, and Modern art eras hang out with each other, navigating the storming, surging seas around them.

Are they coming to enlighten us in our dark times? Or as Roobina Karode writes, has “the artist … gathered what he holds dear and set it away in search of safer shores”?

We should all hope it isn’t so. Perhaps, like the winged creature being pulled up into the boat’s belly, through Sheikh’s work, we can find our way to safer shores, too.