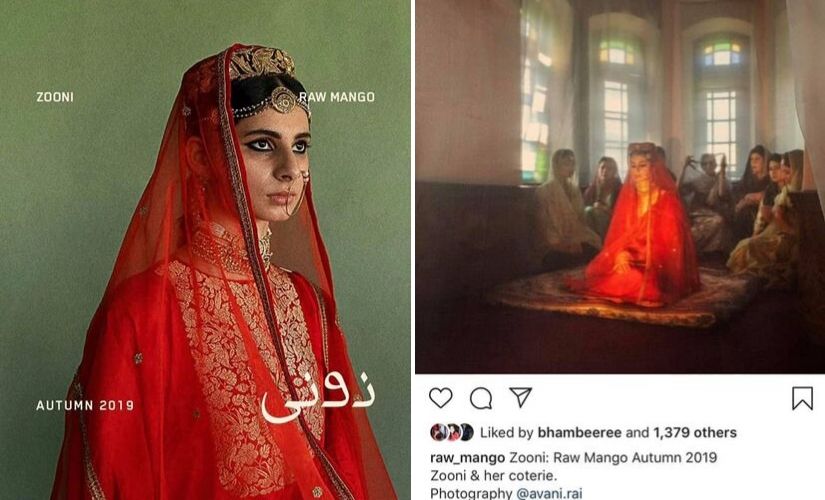

“Presenting Zooni … Because Kashmir is about its people, which needs to be seen and heard.”

On 2 October 2019, Indian fashion house Raw Mango/ Sanjay Garg released on Instagram a series of pictures of a hyper-exotic, deeply (in)grained bridal photoshoot under the name Zooni. Zooni, more famously known as Habba Khatoon, was the ‘last queen’ of Kashmir whose husband, Yusuf Shah Chak, was tricked into prison by a Mughal ruler in a manner almost perfectly repetitive of every Kashmir story.

The pictures in the Raw Mango project were taken by Avani Rai, who also did the art direction for it. Rai is an Indian photographer, who has been very vocal and very quick to share news on social media about the brutalities of the Indian state in Kashmir – without using the words self-determination and/or occupation. We shall come back to this later. She did, however, mention that the pictures were uploaded on the Raw Mango account on this inauspicious moment – and according to various versions of the same story, she claimed that she was either not informed or that the images were published against her will.

The expendable Kashmiri malaise that no one is answerable to

The following day at around 2 am, Raw Mango removed all the Zooni posts secretively and without a public apology either by the company or by Avani Rai.What was written the next day was perhaps even more subtly brazen and disrespectful. Within the first few hours after the posting, among all the back-patting and praises, the images also received an immense backlash from Kashmiris and non-Kashmiris, from people who were hurt and offended that such a series was released while Kashmir was, and still is, reeling under a 60+ day shutdown, with thousands of people detained, brutalised and tortured, mentally, physically, and sexually. The following day at around 2 am, Raw Mango removed all the Zooni posts secretively and without a public apology either by the company or by Avani Rai. What was written the next day was perhaps even more subtly brazen and disrespectful. On its Instagram page, Raw Mango wrote that they had to remove the post due to public sentiment and “assumptions on intent:” the world was not ready for their bold art yet… until the next morning, when those very images showed up in The Hyderabad Times.

It comes from what seems like a belief that Kashmiris (as well as other minorities) are expendable, and they can be accessorised at will, donned and worn out till the last pheran and the last kulcha, and when all is done, a flight can be taken without being answerable to anyone. This lack of sensitivity cannot be seen as a mere editorial, systemic irresponsible handicap. It comes from what seems like a belief that Kashmiris (as well as other minorities) are expendable, and they can be accessorised at will, donned and worn out till the last pheran and the last kulcha, and when all is done, a flight can be taken without being answerable to anyone. This is strikingly similar to how the successive state and central governments, including the PDP, have treated Kashmir and its people. Exactly like how all the talks are always about Kashmiris and almost never with them. Exactly like patriarchy. It reminds of Westworld, an American science fiction TV series, that depicts manufactured ecosystems for economically-able humans to do ‘whatever’ they want to, whenever they wish, with very obedient androids hosting them.

A cruel juxtaposition of timing

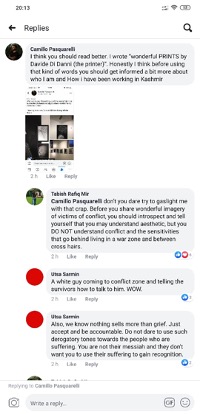

It is not the first time that something like this happened though. It is just a lot more offensive and insensitive now with parents, siblings, and friends locked inside their homes/ prisons; with weddings forced to be furtive affairs, and hearts silenced into submission by a brutal occupation. On September 19th, Italian photographer Camillo Pasquarelli released a few photographs for his exhibition in Rome, Italy, about Kashmiris who were victims of pellet shotguns with captions explaining how “excited” he was and how “wonderful” the prints were. After just a little browsing, I found that he had been travelling to Kashmir and had been supported by some Kashmiri photographers in taking pictures of victims/survivors of the Kashmir conflict that he then exhibited internationally, using similar insensitive language almost everywhere. When called out for his ‘lack of sensitivity’, he asked me (and other Kashmiris on Facebook) to educate ourselves a bit more about his work as well as about Kashmir – the place we all grew up in.

We did educate ourselves about his work and it just seemed to be a cruel predatory exploitation. Coincidentally, Avani Rai also shared his work on Instagram.

Delving deeper into the idea of photography

Rebellions are not symptoms of bad times. We only ever have bad times in Kashmir. Rebellions are symptoms of freedom. On 21 August, Avani Rai was interviewed by The Quint and there she showed a picture of Kashmiri kids playing with toy guns: “These are kids after the day of Eid, playing with guns actually.”What she forgot to mention was that these were toy guns – and that children all over the world ‘play with guns’… But then seamlessly she moved on to imply that every boy who pelts a stone is a potential militant, and that stone pelting and terrorism are synonymous. We all know what the Public Safety Act (PSA) does to dissenters. As a filmmaker, Avani Rai must surely know that montage is a dangerous thing. If she points out to the ‘problem’ of a toy-gun-wielding-child and the fact that we fetishize armed men, aggression, and patriarchy, we probably have movies to credit for. I grew up as a child in downtown Srinagar and my gun-inspiration was always Sunny Deol. Patriarchy, though on steroids in Kashmir, isn’t Kashmir-centric. Guns, like stones, can be good, and/or bad, no? Violence, when defensive, can be good, no? Rebellions are not symptoms of bad times. We only ever have bad times in Kashmir. Rebellions are symptoms of freedom. The convenient grey world of montage narratives and smokescreens can be murderous, no?

In The Quint interview/documentary, Rai speaks to an invisible audience and sometimes to her father with thoroughly exoticized Kashmiri kids as mere background music. In the same interview, what does her father mean when he says “…agar Kashmir hamara hai – jo ki wo hai (…if Kashmir is ours, which in fact it is)’? And what does Avani Rai mean when she says “I am not their spokesperson” and yet in her film, via her father’s rather imposing veteran photographer’s voice, puts across perhaps the most political message for/against Kashmir? Isn’t the struggle/suffering/protest of Kashmir rooted in the denial of self-determination?

The reason she is speaking today is not ‘because very few people are’, as she claims. It’s because very few people are allowed to; and she is allowed to, because of her privilege, her state patronage with PDP and the Tourism Department, and because of her carefully chosen, meticulously curated narrative. “He’s not such a fan of it” – says Avani Rai, pointing to a photograph. Raghu Rai, her photographer father, is not ‘such a fan’ of a photograph of a woman holding up a utensil ridden with bullet holes. We all know that koi utensils mai nahi chupta hai. Conflict ka appropriation bhi nahi (nobody hides in utensils. Not even the appropriation of conflict). The reason she is speaking today is not ‘because very few people are’, as she claims. It’s because very few people are allowed to; and she is allowed to, because of her privilege, her state patronage with PDP and the Tourism Department, and because of her carefully chosen, meticulously curated narrative. In this, she’s not very dissimilar to Iltija Mufti.

…Aur zimmedari bhi hamari honi chahiye (…so the responsibility should be ours too) continues Raghu, almost like the brown equivalent of the white-man burden. This zimmedari statement when spoken in isolation may be easily discounted as innocent, however when spoken in the context of Kashmir, and its relationship with India and Pakistan’s geographical claims, may become an effective way of emasculating the subjugated – a knife in the back, soft and slow: gagging us while caressing our hair.

In her very minimalist, postmodern Mumbai studio, there was nothing from Kashmir except for her own vision of it and her bloated barbed-wire aestheticization of pain. Avani Rai says she creates space for conversation by exhibiting (only) her work around Kashmir. In her very minimalist, postmodern Mumbai studio, there was nothing from Kashmir except for her own vision of it and her bloated barbed-wire aestheticization of pain. Rai’s exhibition was a rather ‘successful’ event, not necessarily monetarily as she often pointed out. It was thoroughly reported, celebrities showed up, people spoke about Kashmir, and a lot of people congratulated her on her work. Surely she thrived in those compliments and flattery and openly shared them as Instagram stories. It was quite exhibitionistic; the exchange of pleasantries, the congratulations, and the thank-yous. Perhaps borderline predatory to the victims, too.

So again, what does Raghu Rai exactly mean when he claims Kashmir as India’s own? Is it the same naive universalism which holds all people, places, palaces and lands equal? All land is acquired, whether by force or diplomacy, ‘acquired’ because no land inherently, or intrinsically, belongs to anyone. India does not belong to Indians like Pakistan does not belong to Pakistanis or any other countries to the people who live on that land. Claim over a land is as (un)real as the ‘value’ of the currency/means with which it is acquired. You live in a place long enough and you call it yours and then the kings and the governments take it from you and they call it theirs and then tax you until they are annexed by more rulers and governments who tax them and so on. Among the paraphernalia of oppression, language is the most oppressive. If you don’t understand that, you understand nothing about modern warfare.

Speaking of language, for example, Avani Rai claims to know quite a bit about Kashmir and its conflict because she has been travelling there for ‘four years’, but still chooses to call gunfights, encounters. Whether you are aware of it or not, the word encounter means and depicts a police act to thwart/end a criminal act, not a militant one. Rai also chooses to show a video about army oppression and uses the phrase ‘security’ forces in the same breath. This doesn’t make sense to me, as the two terms are deeply contradicting – in terminology and essence.

“Agar Kashmir hamara hai, jo ko wo hai…” (If Kashmir is ours, which in fact is…) What does Raghu Rai mean, really? Could it be that he is not aware of the ever-so-reiterated conditions under which the instrument of accession was signed? Does he not know how Kashmir acceded to India? A largely Muslim populace signed over to a newly-formed ‘democracy’ by a Dogra ruler. Signed over, not voted in. The dilution of article 370 over time could also have evaded the collective memory and conscience of mainland Indians. Is it possible that some people visiting Kashmir to understand it, perhaps, tend to miss/skip the most glaring details, the loudest cries, the deepest scars?

People make an aesthetic out of grief, romanticizing it, and selling it as a commodity. Writers do it too. Photography is just a means to this end. Ever since I have written this piece around the appropriation of pain and culture, language and its politics, I have gotten a lot of responses. While a good number of people understand that this essay was about the way language and narratives are used by the state to impose and legitimise violence, others focused solely (and rather aggressively) on the appropriation of culture, or on the Raw Mango controversy. The larger focus of my essay, though, was (Rai’s) problematic use of aesthetic conflict photography (black and white/fisheye/posterization) and the use of a patronising language deliberately to hijack narratives of an oppressed people especially when human rights violations like rapes, killings, and torture are involved. A further concern is that people make an aesthetic out of grief, romanticizing it, and selling it as a commodity. Photography is just a means to this end. Rai isn’t the first one to exploit (Kashmiri) narratives for personal and political gratification and she certainly won’t be the last, because the problem is not only Avani Rai or her father Raghu Rai. It is the way the colonial-settler ideology of entitlement and authoritarianism is implemented. Writers do it too. Photography is just a means to this end. Rai isn’t the first one to exploit (Kashmiri) narratives for personal and political gratification and she certainly won’t be the last, because the problem is not only Avani Rai or her father Raghu Rai. It is the way the colonial-settler ideology of entitlement and authoritarianism is implemented. This is indicative of the methods used to condition people and of audacity that justifies invisibilizing indigenous voices as a deliberate attempt, and not just as a consequence. However, this doesn’t absolve individuals/artist like Avani Rai/Raghu Rai just because they happen to subscribe to an existing idea. They are not victims of it, as some may like to argue. It is a lazy argument made to pass off as existential depth, that they are ‘merely conditioned by it’ – is oversimplified and apologist. People who indulge in it are perhaps just as complicit in the dehumanization, exotification and aestheticization of pain as the criminal system which implements it.