“At no time have governments been moralists. They never imprisoned people and executed them for having done something. They imprisoned and executed them to keep them from doing something. They imprisoned all those prisoners of war, of course, not for treason to the motherland…They imprisoned all of them to keep them from telling their fellow villagers about Europe. What the eye doesn’t see, the heart doesn’t grieve for.”

― Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago, 1918-1956

‘Political Prisoner’ is a category of criminal offense that sits most egregiously in any civilized society, especially in countries that call themselves liberal democracies. It is a thought crime: the crime of thinking, acting, speaking, probing, reporting, questioning, demanding rights, and, more importantly, exercising one’s citizenship. But these inhumane incarcerations do not just target private acts of courage, they are bound together with the fundamental questions of citizenship, and with people’s capacity to hold the State accountable. Especially States that are unilaterally and fundamentally remaking their relationship with their people. The assault on fundamental rights has been consistent and ongoing at a global level and rights-bearing citizens are transformed into consuming subjects of a surveillance State.

In this transforming landscape, dissent is sedition, and resistance is treason.

While the Indian State has a long history of ruthlessly crushing dissent, a new wave of arrests began in 2018. Eleven prominent writers, poets, activists, and human rights defenders have been in prison, held under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act. They are accused of being members of a banned Maoist organization, plotting to kill Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and inciting violent protests in Bhima Koregaon. To date, no credible evidence has been produced by the investigating agency, and those accused remain incarcerated without bail. Since the anti-Citizenship Amendment Act protest began in December 2019, students, activists, and peaceful protesters have been charged with sedition, targeted with violence, and subjected to arrests. Since then, more arrests have followed specifically targeting local Muslim students leader and protestors, including twenty-seven-year-old student leader Safoora Zargar.

Since the COVID-19 lockdown was announced, India’s leading public intellectuals, opposition leaders, writers, thinkers, activists, and scholars have written various appeals to the Narendra Modi government for the release of India’s political prisoners. They are vulnerable to COVID-19 contagion in the country’s overcrowded jails, where three coronavirus-related deaths have already been reported. In response, the State has doubled down and rejected all the bail applications. It also shifted the seventy-year-old journalist Gautham Navlakha from Delhi’s Tihar Jail to Taloja, without any notice or due process – Taloja is one of the prisons where a convict has already died of COVID-19.

A fearful, weak State silences the voice of dissent. Once it has established repression as a response to critique, it has only one way to go: become a regime of authoritarian terror, where it is the source of dread and fear to its citizens.

How do we live, survive, and respond to this moment?

In collaboration with maraa, The Polis Project is launching Profiles of Dissent. This new series centers on remarkable voices of dissent and courage, and their personal and political histories, as a way to reclaim our public spaces.

Profiles of Dissent is a way to question and critique the State that has used legal means to crush dissent illegally. It also intends to ground the idea that, despite the repression, voices of resistance continue to emerge every day.

This profile has been compiled by Tazeen Junaid. You can read Varavara Rao’s profile here, the profile of Sudha Bharadwaj here, that of GN Saibaba here, Gautham Navlakha’s profile here, Anand Teltumbde here, Sharjeel Usmani here, Shoma Sen here, Surendra Gadling here, Asif Iqbal Tanha here, Rona Wilson here, Sudhir Dhawale here, Sharjeel Imam here, Arun Ferreira here, Umar Khalid here, Father Stan Swami here, K. Satyanarayana here, Mahesh Raut here and Hany Babu here.

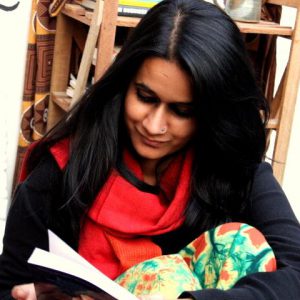

NATASHA NARWAL

Natasha Narwal, 31, is a research scholar from Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) in New Delhi. She is also a gender activist and a founding member of Pinjra Tod: Break the Hostel Locks, a collective of female students and alumnae of Delhi colleges campaigning to end punitive policies against women in universities, including discriminating curfew timings in hostels. She grew up witnessing her father’s activism in the teachers’ front of Chaudhary Charan Singh Haryana Agricultural University, which made her aware of the struggles for social justice in India.

In 2004, Narwal strongly reacted when former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee declared in an election campaign that the Bharatiya Janta Party (BJP) does not want Muslim votes. She condemned such rhetoric by calling it “extremely wrong,” and, at the young age of 15, became a strong proponent of social justice as she felt that right-wing groups affiliated with the BJP were ostracizing religious minorities in India.

Narwal moved to Delhi in 2006 to pursue higher education at Delhi University (DU). Her interest in socio-political causes made her join the Students’ Federation of India (SFI) – a left-wing student organization politically aligned to the Communist Party of India (Marxist) and contest for the posts of president and secretary in DU Students Union as SFI candidate. She completed her Bachelor degree in Modern History from the Hindu College and her Master’s degree from the History Department in DU. In 2012 she enrolled for an MPhil in Development Practice at Dr. B. R. Ambedkar University in Delhi where she studied access to land rights for tribal communities in the Rayagada district of Odisha. After completing her MPhil in 2014, she took a break to prepare for the National Eligibility Test of Junior Research Fellowship.

Narwal was brought up in Hisar, Haryana, known as the rape capital of India. This hostile context, however, did not turn her into a victim of patriarchal structures. Her father’s reiteration of Safdar Hashmi’s slogan “Aurtein uthi nahi to zulm badhta jaega. (If women don’t rise, the injustice will keep increasing)” taught her to resist the institutionalized discrimination against women. Later on, experiencing misogynistic prejudice in educational institutions motivated her to focus on issues related to gender equality and equal opportunities in Indian universities. She, along with other like-minded activists, founded Pinjra Tod in 2015 in an effort to end discrimination against women in educational institutions.

Narwal’s political position against the rampant rise of Hindutva became visible during her participation in a 2017 Pinjra Tod demonstration, where the group was protesting Union Minister for Women and Child Development Maneka Gandhi’s endorsement of curfew timings in women’s hostels. Narwal argued that the misogynistic nature of Hindutva promotes the patriarchal concept of a nurturing woman and limits her from being completely free. When asked to explain a slogan she raised in the protest, Bharat ki mata nahi banenge (We won’t become mothers to India), she said: “This government, the BJP government, the right wing government and their students’ outfit ABVP [Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad] has been trying to impose on women students this notion of Bharat Mata [Indian Mother Goddess], of the pure woman. This statement by Maneka Gandhi comes from the notion of certain kind of women who will be locked up inside their hostels, will not exercise their own sexuality and will concur to being docile. That is why we want to tell this government, the ABVP, and Maneka Gandhi that we won’t become Mother India. We will not. Bharat ki mata hum nahi banenge because the concept of Bharat Mata cages women into a certain notion of a docile, obedient woman who cannot exercise her own choice, agency, and sexuality.”

In the time she took off studying, she worked for the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies and the Society for Rural Urban and Tribal Initiative; volunteered on research projects; worked on a documentary on Khaps (patriarchal non-governmental village bodies with significant social influence), as a freelance translator and as an investigative journalist for Newsclick. Her writings also appeared on The Wire and Kafila. She enrolled as a research scholar at the Center for Historical Studies at JNU in 2018 and started her Ph.D. thesis on the history of the women’s movement in Delhi.

The peaceful Chakka Jaam protest at Shaheen Bagh led by Muslim women against the implementation of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and the National Register of Citizens (NRC) inspired Narwal to participate in several anti-CAA protests including at Shaheen Bagh, at Jafrabad metro station in Delhi and at Ghantaghar in Lucknow.

The Delhi Police seized Narwal’s phone on 19 April 2020 and forced her to disclose its passcode. On 23 May, she was interrogated by a team of Special Unit officers for two hours along with Devangana Kalita. Just as the interrogation ended, another team of Jaffrabad Police arrived at their house and arrested both of them for blockading a road near Jaffrabad metro station on 22 February as part of an anti-CAA Chakka Jaam protest. They were charged for using force even though the First Information Report (FIR) of the incident did not mention anyone being violent.

Narwal was granted an oral bail on the following day as the non-bailable charge of using force was dismissed as non-maintainable. When the Delhi Police heard of the bail orders, the Crime Branch of Delhi Police immediately appeared in Court in a mala fide manner and sought to prolong her custody under another FIR. This FIR was filed on events that took place on 25 February near the Jaffrabad metro station and, even though the document did not name her directly, the Court sentenced her to judicial custody till 11 June. While in custody, she was charged with the non-bailable Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) on 29 May for her alleged role in the “conspiracy” inciting the February 2020 Delhi pogrom as part of a coordinated attempt to defame Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Civil society organizations condemned Narwal’s prolonged incarceration. They have accused Delhi Police of trying to shift the blame from Kapil Mishra, a BJP member who led a pro-CAA demonstration in northeast Delhi and gave an incendiary speech just before the February 2020 Delhi pogrom, onto activists who are mostly Muslim. To date, Mishra has not been charged with any misconduct.

Date of arrest: 23 May 2020

Charges: Natasha Narwal has been named in three FIRs filed separately by different units of the Delhi Police in May 2020. She has been primarily accused of protesting at Jaffrabad metro station and being a co-conspirator in the February 2020 Delhi pogrom.

The FIR 48/2020 filed by Jaffrabad Police alleges that Narwal blockaded a road near Jaffrabad metro station on 22 February as part of an anti-CAA Chakka Jaam protest and charged her with Indian Penal Code (IPC) Sections 147 (Rioting), 341 (Wrongful restraint) and 353 (Assault or criminal force to deter public servant from discharge of his duty). She has been bailed in this case. The FIR 50/2020, investigated by the Crime Branch, alleges that Narwal was part of a conspiracy to cause riots near Jaffrabad metro station which resulted in one death and charges her with various Sections including 302 (Murder) of IPC along with the Arms Act and the Prevention of Damage to Public Property Act. She has been bailed in this case as well. The FIR 59/2020, filed by the Crime Branch, accused Narwal of establishing a sit-in protest at 66 Foota Road of Seelampur, blockading Jaffrabad metro station, and abetting the February 2020 Delhi pogrom. Even though she was not directly named in this FIR, she was arrested while under judicial custody in Tihar Jail and charged with several UAPA sections for committing terrorist acts and raising funds for terrorist acts as well as with relevant sections of the IPC, Arms Act, and Prevention of Damage to Public Property Act.

Location of work: Delhi and Haryana.

Update: Natasha Narwal remains incarcerated in Tihar Jail, where for a while she was not allowed to communicate with her lawyer and family. Her counsel submitted her complaints in the Delhi High Court and she was later permitted video conferencing with her lawyer and daily five-minute phone calls with her family. She was also allowed to source books and reading material from outside the jail. She looks after the jail’s library, teaches her fellow prisoners yoga, and plays with children.

Letters from jail

The following is a compilation of unpublished excerpts given from letters Natasha Narwal has written since her incarceration in Tihar Jail in May 2020. Narwal is the jail librarian now and that keeps her busy. Letters and gifts from friends as well as regular conversations with family members keep her connected to the world outside. She has many stories to tell, some of which she writes in letters. The women and children inside prison have become her companions. She has been writing to her friends about the communities of love and care that prisoners build together. She values the importance of small events like the moments when everyone gathers around those who have received a letter.

How long will or can the moon be caged?

“The kids are really fascinated by the squirrels that dance up and down. Especially a Brazilian boy with cute curly hair. He was born in jail itself two years back on Christmas day. He is a true prison baby, loved and pampered by everybody. And he really knows it and exploits it. He knows he can get away with anything with his cute face and has become a brat. Sometimes he does yoga with me and then climbs all over me. The other kids then join me and then I have to become a horse!” Spending time with kids, Narwal wonders what these formative years in prison will do to their minds and bodies and how they will view the outside world when they get out.

Prison life, Narwal wrote, has been humbling. “How little we know about lives of people who live in jail for years without trial and bail, without any visibility to the outside world?” One of the first observations she shared with friends had to do with similarities between how women are caged by society and in jail.

“I can also glimpse the moon from our barrack window. It’s caged in the grills but the moonlight is coming to us filtering through them. Before coming inside our ward to be locked, I managed to see some stars as well giving the moon some company. I don’t know when one will be able to see the night sky without these grills and bars. How long will or can the moon be caged, hum dekhenge (We will see).”

No one should have the right to deny and restrict our mobility: Natasha Narwal’s Facebook Post (28 August 2015)

When I first came to Delhi to study, I lived in PG [Paying Guest] hostel since the prestigious Hindu College of Delhi University did not have a girls hostel. This PG had a rather ‘liberal’ deadline of 10 pm and I along with others living there considered ourselves really lucky to have found this PG. We did not feel much restricted when we were locked up after 10 pm as the horizon of freedom was measured in terms of relative deadlines of different hostels. But sitting in the balcony at night, we would sometimes long to go to the park right in front of the hostel for a walk or have an ice cream from the vendor right around the street corner but couldn’t. Gradually the locks started disturbing us more and more and by the end of the year, a bunch of us decided to venture out of the hostel where we could live on our own terms.

While hunting for houses, we had to encounter several property dealers/brokers who would give us a slanting look or a smirk when we told them we want a house with ‘free entry’. And the landlords were even more concerned about our safety as they saw us as their own daughters and were very eager to again lock us up at night and restrict the entry of male friends (though they did not mind charging exorbitant rents from their ‘own daughter’).

Over time we learnt that being women, in this city, we may never find a place where we can really live on our own terms and such a possibility can come our way only as the goodwill of some landlord or his/her absence and not as our right. We compromised with the locks but never gave up on devising ways to sneak through them. Be it in the form of convincing the landlords of our ‘decency’ to win some concessions, smuggling in male friends, making duplicate keys, jumping over the gates at night to meet a lover, we refused to abide.

Though such sneaking had its share of fun and thrill but I feel that no one should have the right to deny and restrict our mobility and access to different experiences and spaces. And I sincerely hope that by getting our voices together and shouting loudly we can break these locks.