Did the Modi Govt Use the Frenzy Around War To Introduce Harsher Censorship Measures?

Less than 24 hours after the Indian armed forces launched ‘Operation Sindoor’ on May 9—in retaliation for the Pahalgam attack on Apr 22—the Ministry of Information & Broadcasting (MIB) issued an advisory stating that “all OTT platforms are mandated to remove all content originating in Pakistan.”

It was a somewhat odd directive—very little Pakistani content actually plays on Indian OTT platforms, except for shows on Zee Zindagi (a part of Zee5) and the odd show on YouTube. However, it was not unforeseeable, given that this government had reacted similarly in light of the Uri attacks in 2016, when Pakistani actors and singers were banned from working in India. Merely weeks after Uri, there were widespread protests against Ae Dil Hai Mushkil (2016) for platforming the immensely popular Pakistani actor, Fawad Khan, as a part of the primary cast.

It prompted director Karan Johar to put out a video statement—which looked eerily like a hostage video—pleading with the powers that be to allow the film to release without incident. Ae Dil Hai Mushkil finally released on October 28, 2016.

Cruelly enough, Fawad Khan had another film release on May 9, 2025—Abir Gulaal, with Vaani Kapoor, which disappeared like it never existed. Actor Vaani Kapoor’s Instagram account, which was brimming with the film’s promos and songs, suddenly had no mention of it. The film was initially showing on ticketing platforms and then removed.

The latest advisory came days after the Instagram accounts of Atif Aslam, Fawad Khan, Mahira Khan, and Hania Amir were geo-blocked in India. It mentioned that these measures had been undertaken for reasons related to ‘national security’.

The advisory cites Rule 3(1)(b) under the IT Rules 2021—”where a publisher is supposed to take into consideration the following factors: content which affects sovereignty and integrity of India; content which threatens, endangers or jeopardises the security of the State; content which is detrimental to India’s friendly relations with foreign countries; and content which is likely to incite violence or disturb the maintenance of public order.”

Coincidentally, the rule borrows its phrases like “sovereignty & integrity”, “friendly relations with foreign countries” and “public order” from Section 5B(1) of the Cinematograph Act, 1952—one of the most commonly cited sections to censor films that are even slightly critical of the establishment like Udta Punjab (2016) and S Durga (2018)—the two films that brought the state’s censorial role to the fore in the last decade.

Hence, the motivation behind the advisory is worth unpacking: what does the removal of Pakistani content have to do with national security? Does it give India a diplomatic edge during its war with Pakistan? Or is the frenzy around it being used by the BJP government to introduce harsher censorship measures?

New Delhi-based Internet Freedom Foundation (IFF) was among the earliest to comment on the advisory, noting that it calls for “vague forms of censorship”—much like the 2024 Broadcast Services (Regulation) Bill. An early draft of the bill sought to introduce compliance requirements for creators (including journalists who had quit mainstream media and moved to YouTube in the last few years). These requirements included mandatory registration of all content creators and platforms with the government, prior intimation of content schedules, and the ability for the Union Government to direct content takedowns or block platforms without prior judicial review.

Until now, the Indian Internet was largely unregulated, except for “grossly offensive” remarks punishable under section 66A of the Information Technology Act, 2000. This has also long been criticized for its vagueness and subjectivity, allowing it to be weaponized to arrest individuals for merely posting comments deemed critical of politicians, sharing satirical content, or forwarding memes.

In 2012, for instance, Shaheen Dhada was arrested for posting a Facebook status questioning why Mumbai should shut down for the funeral of Shiv Sena chief Bal Thackeray. Her friend Rinu Srinivasan, who merely liked the post, was also arrested. That same year, political cartoonist Aseem Trivedi was arrested under 66A for publishing cartoons critical of government corruption and the Indian Constitution. He was even charged with sedition.

The Supreme Court eventually struck down Section 66A as unconstitutional in 2015. After many adverse remarks, the government withdrew the 2024 Broadcast Services (Regulation) Bill in August last year. But when asked if it would be a stretch to see the latest advisory as a proxy for the 2024 Bill, Internet Freedom Foundation (IFF) founder Apar Gupta answered in the affirmative.

“The advisory employs identical vocabulary—‘OTT platforms’, ‘Code of Ethics’ (a code requiring OTT platforms to not broadcast content that might be deemed ‘harmful’ or violating an Indian law), ‘public order’ (the absence of disorder, violence, or disturbance that might threaten the functioning of society or the authority of the state)—that the draft bill used,” he noted. “IFF’s statement calls the advisory ‘sweeping censorship’ that skips the consultative process expected of primary legislation.”

A crucial extract from the IFF statement in response to the advisory reads as follows:

“… its vaguely worded direction to ‘discontinue’ any material originating in Pakistan may include—potentially everything from an Indian journalist’s interview with a Pakistani commentator to cross-border cultural programming such as joint concerts by Indian artists—and will result in over-compliance and self-censorship by private service providers, gutting the freedom of speech and liberty that sustains our democracy. Given this we fear overcompliance and censorship, as the advisory offers neither notice nor a chance to contest takedowns. It also is not limited by itself to any period of time or event and hence is not temporary…”

When asked if the advisory offers any strategic advantage to India during the conflict, veteran journalist Paranjoy Guha Thakurta didn’t mince his words, calling it a “stupid” decision. “Today, people can access Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) and access the same content,” he said. “If our Minister of Information & Broadcasting (Ashwini Vaishnaw) doesn’t realize such a simple fact, I don’t know what world they’re living in.”

Filmmaker Dibakar Banerjee doesn’t see the removal of Pakistani content as a high-priority issue right now, but is interested in seeing if the advisory continues in case a war is averted. As of writing, there has been no official announcement rolling it back.

Academic and former JNU professor Ira Bhaskar also felt that the optics aren’t quite right for a cultural exchange with Pakistan at this moment. However, she questioned the government’s motivations in blocking Indian news platforms such as The Wire and Maktoob Media.

“These are news outlets, it’s not a cultural exchange,” Bhaskar stated. “For example, Karan Thapar’s interview with Najam Sethi—he’s a reputed journalist from across the border, and we’re talking about news analysis.”

Bhaskar opined that the blocking could have to do with how these alternative media platforms are being more balanced in their reporting. “Someone sent me a video clip where a journalist is saying, ‘Mazaa aa gaya’ (from Times NOW) and they’ve turned war into a video game,” she recalled. “What kind of nonsense is this? Not only is it unethical, it’s also dangerous for our internal security. Why aren’t they being blocked?”

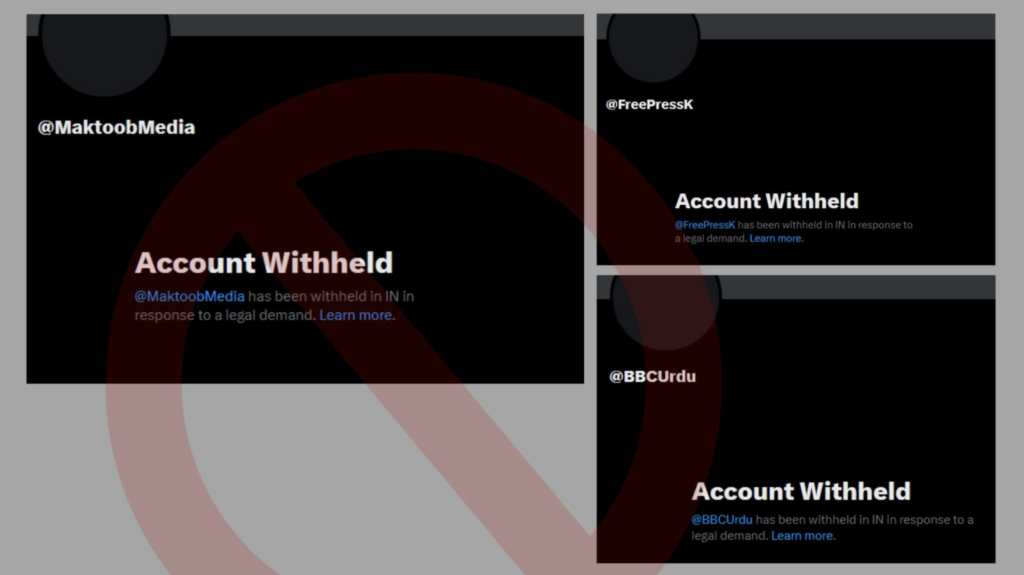

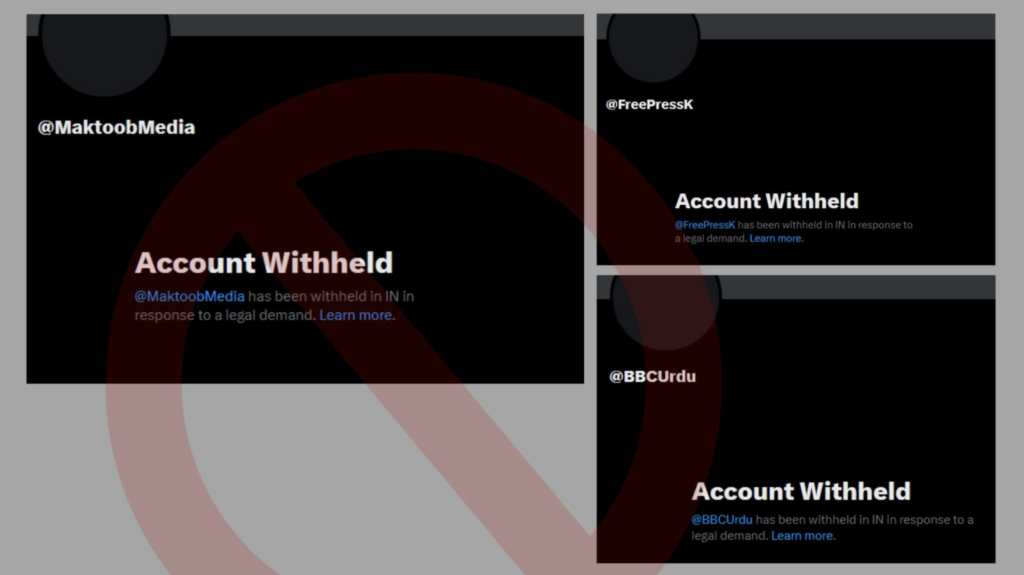

Guha Thakurta underlined how only a particular kind of journalist or platform is being blocked by the government, like Anuradha Bhasin, BBC Urdu, and Kashmiriyat. They’re among the 8,000 X (formerly Twitter) accounts blocked in India, citing a “legal” demand against them on May 9.

X (formerly known as Twitter) has been involved in a legal battle centering on censorship of free speech, with the Indian government in the Karnataka High Court since March, 2025—challenging the government’s use of section 79(3)(b) of the IT Act—that authorizes it to block an ‘intermediary’ for circulating “unlawful” content. Specifically, X has alleged that the government of India is using “an impermissible parallel mechanism” which blocks content online and allows the government to remove illegal online content. This, X claims, avoids the legal process laid out for content regulation as per the IT Act.

“[The blocking is] a tacit acknowledgement that the so-called godi media is on their side, so they’re going after the YouTubers,” observed Guha Thakurta.

At the time of writing this, most of the blocked X accounts have been restored—with Outlook India’s X account reappearing within 24 hours, The Kashmiriyat and Maktoob Media had their accounts restored on May 18—a full week after the first reports of a ceasefire announcement. Some accounts, like that of journalist Anuradha Bhasin, continue to be withheld to date.

Restrictions intended to be limited to OTT platforms in the advisory could slowly permeate other social media platforms, too. Apar Gupta mentioned how this government has consistently expanded their digital-speech control during crises. “The wartime atmosphere supplies the ‘national security’ justification absent in calmer times,” he said, noting how the Rule 3(1)(b) invoked for OTT platforms also applies to intermediaries such as YouTube, Instagram, and X. “The trajectory—advisory → platform compliance → expanded takedown orders—mirrors the playbook used against news websites during earlier domestic protests.”

Gupta is likely alluding to the farmers’ protests (November 2020-December 2021) and anti-CAA protests (December 2019-March 2020), when platforms like Meta and X (formerly Twitter) were asked to take down posts or temporarily block accounts that were most actively organizing and amplifying the protests. This included the actual protestors themselves but also journalists, activists, and other outspoken critics of the government with meaningful reach.

A well-known actor, who didn’t wish to be named, was surprised that the directive applied to India’s OTT platforms. “They don’t have to do anything to OTT platforms, all of them are bowing down already. They have literally destroyed filmmaking,” they observed.

Bhaskar is curious that the government’s attention is diverted to the media during active conflict. “Banning Pakistani channels during a war is still understandable,” she said, emphasizing the temporary nature of such a ban, “but not having access to our own channels is a completely different thing.”

For Dibakar Banerjee, this censorship is not a new phenomenon. “As a filmmaker whose film (Tees) has been restricted from release by an OTT platform (Netflix), this is not new news,” he said. “We should not pretend to ourselves that this just started.”

Related Posts

Did the Modi Govt Use the Frenzy Around War To Introduce Harsher Censorship Measures?

Less than 24 hours after the Indian armed forces launched ‘Operation Sindoor’ on May 9—in retaliation for the Pahalgam attack on Apr 22—the Ministry of Information & Broadcasting (MIB) issued an advisory stating that “all OTT platforms are mandated to remove all content originating in Pakistan.”

It was a somewhat odd directive—very little Pakistani content actually plays on Indian OTT platforms, except for shows on Zee Zindagi (a part of Zee5) and the odd show on YouTube. However, it was not unforeseeable, given that this government had reacted similarly in light of the Uri attacks in 2016, when Pakistani actors and singers were banned from working in India. Merely weeks after Uri, there were widespread protests against Ae Dil Hai Mushkil (2016) for platforming the immensely popular Pakistani actor, Fawad Khan, as a part of the primary cast.

It prompted director Karan Johar to put out a video statement—which looked eerily like a hostage video—pleading with the powers that be to allow the film to release without incident. Ae Dil Hai Mushkil finally released on October 28, 2016.

Cruelly enough, Fawad Khan had another film release on May 9, 2025—Abir Gulaal, with Vaani Kapoor, which disappeared like it never existed. Actor Vaani Kapoor’s Instagram account, which was brimming with the film’s promos and songs, suddenly had no mention of it. The film was initially showing on ticketing platforms and then removed.

The latest advisory came days after the Instagram accounts of Atif Aslam, Fawad Khan, Mahira Khan, and Hania Amir were geo-blocked in India. It mentioned that these measures had been undertaken for reasons related to ‘national security’.

The advisory cites Rule 3(1)(b) under the IT Rules 2021—”where a publisher is supposed to take into consideration the following factors: content which affects sovereignty and integrity of India; content which threatens, endangers or jeopardises the security of the State; content which is detrimental to India’s friendly relations with foreign countries; and content which is likely to incite violence or disturb the maintenance of public order.”

Coincidentally, the rule borrows its phrases like “sovereignty & integrity”, “friendly relations with foreign countries” and “public order” from Section 5B(1) of the Cinematograph Act, 1952—one of the most commonly cited sections to censor films that are even slightly critical of the establishment like Udta Punjab (2016) and S Durga (2018)—the two films that brought the state’s censorial role to the fore in the last decade.

Hence, the motivation behind the advisory is worth unpacking: what does the removal of Pakistani content have to do with national security? Does it give India a diplomatic edge during its war with Pakistan? Or is the frenzy around it being used by the BJP government to introduce harsher censorship measures?

New Delhi-based Internet Freedom Foundation (IFF) was among the earliest to comment on the advisory, noting that it calls for “vague forms of censorship”—much like the 2024 Broadcast Services (Regulation) Bill. An early draft of the bill sought to introduce compliance requirements for creators (including journalists who had quit mainstream media and moved to YouTube in the last few years). These requirements included mandatory registration of all content creators and platforms with the government, prior intimation of content schedules, and the ability for the Union Government to direct content takedowns or block platforms without prior judicial review.

Until now, the Indian Internet was largely unregulated, except for “grossly offensive” remarks punishable under section 66A of the Information Technology Act, 2000. This has also long been criticized for its vagueness and subjectivity, allowing it to be weaponized to arrest individuals for merely posting comments deemed critical of politicians, sharing satirical content, or forwarding memes.

In 2012, for instance, Shaheen Dhada was arrested for posting a Facebook status questioning why Mumbai should shut down for the funeral of Shiv Sena chief Bal Thackeray. Her friend Rinu Srinivasan, who merely liked the post, was also arrested. That same year, political cartoonist Aseem Trivedi was arrested under 66A for publishing cartoons critical of government corruption and the Indian Constitution. He was even charged with sedition.

The Supreme Court eventually struck down Section 66A as unconstitutional in 2015. After many adverse remarks, the government withdrew the 2024 Broadcast Services (Regulation) Bill in August last year. But when asked if it would be a stretch to see the latest advisory as a proxy for the 2024 Bill, Internet Freedom Foundation (IFF) founder Apar Gupta answered in the affirmative.

“The advisory employs identical vocabulary—‘OTT platforms’, ‘Code of Ethics’ (a code requiring OTT platforms to not broadcast content that might be deemed ‘harmful’ or violating an Indian law), ‘public order’ (the absence of disorder, violence, or disturbance that might threaten the functioning of society or the authority of the state)—that the draft bill used,” he noted. “IFF’s statement calls the advisory ‘sweeping censorship’ that skips the consultative process expected of primary legislation.”

A crucial extract from the IFF statement in response to the advisory reads as follows:

“… its vaguely worded direction to ‘discontinue’ any material originating in Pakistan may include—potentially everything from an Indian journalist’s interview with a Pakistani commentator to cross-border cultural programming such as joint concerts by Indian artists—and will result in over-compliance and self-censorship by private service providers, gutting the freedom of speech and liberty that sustains our democracy. Given this we fear overcompliance and censorship, as the advisory offers neither notice nor a chance to contest takedowns. It also is not limited by itself to any period of time or event and hence is not temporary…”

When asked if the advisory offers any strategic advantage to India during the conflict, veteran journalist Paranjoy Guha Thakurta didn’t mince his words, calling it a “stupid” decision. “Today, people can access Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) and access the same content,” he said. “If our Minister of Information & Broadcasting (Ashwini Vaishnaw) doesn’t realize such a simple fact, I don’t know what world they’re living in.”

Filmmaker Dibakar Banerjee doesn’t see the removal of Pakistani content as a high-priority issue right now, but is interested in seeing if the advisory continues in case a war is averted. As of writing, there has been no official announcement rolling it back.

Academic and former JNU professor Ira Bhaskar also felt that the optics aren’t quite right for a cultural exchange with Pakistan at this moment. However, she questioned the government’s motivations in blocking Indian news platforms such as The Wire and Maktoob Media.

“These are news outlets, it’s not a cultural exchange,” Bhaskar stated. “For example, Karan Thapar’s interview with Najam Sethi—he’s a reputed journalist from across the border, and we’re talking about news analysis.”

Bhaskar opined that the blocking could have to do with how these alternative media platforms are being more balanced in their reporting. “Someone sent me a video clip where a journalist is saying, ‘Mazaa aa gaya’ (from Times NOW) and they’ve turned war into a video game,” she recalled. “What kind of nonsense is this? Not only is it unethical, it’s also dangerous for our internal security. Why aren’t they being blocked?”

Guha Thakurta underlined how only a particular kind of journalist or platform is being blocked by the government, like Anuradha Bhasin, BBC Urdu, and Kashmiriyat. They’re among the 8,000 X (formerly Twitter) accounts blocked in India, citing a “legal” demand against them on May 9.

X (formerly known as Twitter) has been involved in a legal battle centering on censorship of free speech, with the Indian government in the Karnataka High Court since March, 2025—challenging the government’s use of section 79(3)(b) of the IT Act—that authorizes it to block an ‘intermediary’ for circulating “unlawful” content. Specifically, X has alleged that the government of India is using “an impermissible parallel mechanism” which blocks content online and allows the government to remove illegal online content. This, X claims, avoids the legal process laid out for content regulation as per the IT Act.

“[The blocking is] a tacit acknowledgement that the so-called godi media is on their side, so they’re going after the YouTubers,” observed Guha Thakurta.

At the time of writing this, most of the blocked X accounts have been restored—with Outlook India’s X account reappearing within 24 hours, The Kashmiriyat and Maktoob Media had their accounts restored on May 18—a full week after the first reports of a ceasefire announcement. Some accounts, like that of journalist Anuradha Bhasin, continue to be withheld to date.

Restrictions intended to be limited to OTT platforms in the advisory could slowly permeate other social media platforms, too. Apar Gupta mentioned how this government has consistently expanded their digital-speech control during crises. “The wartime atmosphere supplies the ‘national security’ justification absent in calmer times,” he said, noting how the Rule 3(1)(b) invoked for OTT platforms also applies to intermediaries such as YouTube, Instagram, and X. “The trajectory—advisory → platform compliance → expanded takedown orders—mirrors the playbook used against news websites during earlier domestic protests.”

Gupta is likely alluding to the farmers’ protests (November 2020-December 2021) and anti-CAA protests (December 2019-March 2020), when platforms like Meta and X (formerly Twitter) were asked to take down posts or temporarily block accounts that were most actively organizing and amplifying the protests. This included the actual protestors themselves but also journalists, activists, and other outspoken critics of the government with meaningful reach.

A well-known actor, who didn’t wish to be named, was surprised that the directive applied to India’s OTT platforms. “They don’t have to do anything to OTT platforms, all of them are bowing down already. They have literally destroyed filmmaking,” they observed.

Bhaskar is curious that the government’s attention is diverted to the media during active conflict. “Banning Pakistani channels during a war is still understandable,” she said, emphasizing the temporary nature of such a ban, “but not having access to our own channels is a completely different thing.”

For Dibakar Banerjee, this censorship is not a new phenomenon. “As a filmmaker whose film (Tees) has been restricted from release by an OTT platform (Netflix), this is not new news,” he said. “We should not pretend to ourselves that this just started.”

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.