India’s changes in Kashmir domicile law seek to change its demography, fulfil definition of genocide

In an open letter to UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres and the UN Security Council, a group of Kashmir scholars has sought ‘immediate intervention in the unacceptable political situation precipitated by the illegal and malafide amendments made by India.’ The letter is reproduced below.

We, the Kashmir Scholars Consultative and Action Network, are an interdisciplinary group of scholars of various nationalities engaged in research on the disputed territory of Jammu and Kashmir. We write to seek your immediate intervention in the unacceptable political situation precipitated by the illegal and malafide amendments made by India to the domicile law that obtains in the disputed territory of Jammu and Kashmir. These changes in the domicile law pave the way for deliberate demographic change in the region—an issue Kashmiris have increasingly raised since the Government of India unilaterally abrogated the treaty-based, constitutional relationship between India and the State of Jammu and Kashmir on August 5, 2019. Since then, as you are aware, an inhumane lockdown has been in place in Kashmir.

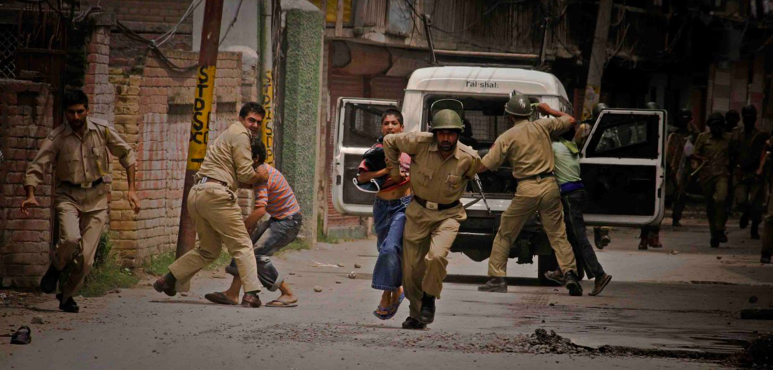

This lockdown has caused enormous hardships for the people of Kashmir. A curfew was imposed for several months. A complete communication blackout was imposed, with landline and cellphone facilities suspended and internet completely banned. Thousands of Kashmiris—civilians, politicians, and activists—were illegally arrested and preemptively detained; hundreds of political prisoners are still languishing in jails. Most of them are imprisoned hundreds of miles away from their homes, with access to neither their families nor legal representation, under some of the most draconian laws imaginable, including the Public Safety Act (PSA), aptly called the “lawless law” by Amnesty. Even at this critical juncture of the COVID-19 pandemic, especially dangerous for people kept in close quarters or those with underlying conditions, India has granted no relief to Kashmiri political prisoners despite the clear urging of Michelle Bachelet, the UN High Commissioner of Human Rights. Kashmir is in the midst of a dangerous health crisis; its healthcare professionals are bravely dealing with a high percentage of COVID-19 cases deeply exacerbated by dearth of provisions for testing and an overall insufficient health infrastructure, epitomized by a total of mere 97 ventilators for a population of more than seven million in the Kashmir valley, many of which are out of order or already being used for other patients. The overall situation is dangerously worsened as India continues to deny the people of Jammu and Kashmir the fundamental rights to expression, communication, and information. All of these rely upon access to functional and fast internet, which in Kashmir is being kept 2,000-20,000 times slower via deliberate withholding of the 4G network. Health care professionals engaged in countering the pandemic have argued that they are not able to download basic health information, including from the World Health Organization, in an efficient manner, with consequent risks for public health at this crucial moment.

India is pursuing its aggressive policies backed up by these new and draconian domicile laws with an intent to alter the results of the plebiscite, if ever held, in its favour. On March 31, 2020, with much of the world busy responding to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Indian government furthered its most recent illegal and immoral initiatives against the people of Jammu and Kashmir through the introduction of a new “domicile” law. Prior to August 5, 2019, only historic residents or “state subjects” of Jammu and Kashmir had certain special rights (ultimately flowing from the pre-1947 laws of Jammu and Kashmir and the limited, conditional, treaty-based accession by the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir to India in 1947) including the right to own immovable property and to be eligible for certain public sector jobs. This new domicile law grants residency to Indians who have lived in Jammu and Kashmir for fifteen years, even if that residency was enabled by being part of the military deployment in place or as part of the occupying forces in the region. Domicile has also been legalized for those who have studied in Kashmir for seven years and appeared in class 10 and 12 examinations in any institution in J&K. This allows even children of the central government officials who have served in any capacity in Jammu and Kashmir to become eligible for residency and thus to qualify for local jobs. Initially only the lowest cadre of jobs was reserved for state subjects of Jammu and Kashmir while all other jobs were opened up for residents of India. Under pressure from members of the ruling political party and other political allies who supported the original changes made to the status of J&K, the Government of India speedily amended the legislation on April 4 to reserve all government jobs for “domiciles”, which now includes all Indians who will be considered residents as per the revised rules.

This clearly aimed at demographic change has serious consequences for Jammu and Kashmir and suggests the implementation of plans that scholars have openly called Israeli-style settler colonialism.

1. While these recent aggressive changes in Indian domestic law do not alter the international position that Kashmir is a disputed/occupied territory, these domestic laws, guided by Indian policy to change the demographic composition of Kashmir, will adversely impact the welfare, well-being and future of the state subjects of Jammu and Kashmir. It is also against the UN SC resolutions namely: SCR 47 (1948), SCR 91 (30 March 1951), SCR 96 (10 November 1951), SCR 98 (23 December 1952), SCR 122 (24 January 1957), and SCR 126 (2 December 1957) that call for the conduct of a plebiscite to determine the future of the disputed territory of Jammu and Kashmir. Clearly, India is pursuing its aggressive policies backed up by these new and draconian domicile laws with an intent to alter the results of the plebiscite, if ever held, in its favour. Hence there is an urgent need to protect the historical rights of Kashmiris with immediate effect.

2. These intended demographic changes can productively be argued to fulfil the definition of genocide under the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, UN General Assembly Resolution 260, as acts committed “with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such”. Given that the transnational, well-respected group Genocide Watch has already placed Kashmir on Genocide Alert, the genocidal intent of the Indian state is well established. The response of the Indian State, or lack thereof, to the current global crisis of COVID-19 pandemic, as described earlier in this letter, is a case in point.

3. India (more than 1.3 billion population) is imposing upon the besieged indigenous peoples of Jammu and Kashmir (about 13 million in the area under Indian administration) forms of assimilation by Indian cultures and ways of life via a spate of legislative and administrative acts since August 5, 2019, specifically the most recently proposed domicile law which explicitly enables a deliberate change of demography in a disputed area. Thus the even more pertinent perspective on the situation in Indian Administered Jammu and Kashmir is through the framework of UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, 2007. This critically includes land rights (including reparation, or return of land i.e. Article 10) to environmental issues (Articles 26 -30, and 32). This proposed extension of domicile rights to Indian citizens is precisely an action aimed at depriving peoples of Jammu and Kashmir of their integrity as distinct peoples, and of their cultural values or ethnic identities. Already there have been debates about changing official and state languages. The form of population transfer which is being enabled by the new domicile law has the overt aim of violating and undermining the rights of the indigenous peoples of Jammu & Kashmir to employment in the public sector and admission in institutions of higher education. A more detailed analysis of this issue can be found in our earlier Indigenous peoples report.

4. With this new domicile law, there is also a great threat to the land, fragile ecology, and resources of the region. India must be required to respect the laws of protection of natural resources as provided under Article 1 of ICCPR and ICESCR; Charter of the United Nations, as well as General Assembly resolution on Permanent sovereignty over natural resources 1962 and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, 2007.

5. As per the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, all people have the right to speak on matters that affect their lives. Kashmiris have been consistently denied that right, with increased intensity since August 5, 2019. After the passing of the domicile law, the police are issuing threats to arrest anyone voicing dissent online. This is happening while Kashmiris are quarantined due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Their ability to communicate is already compromised because by Indian order their internet is deliberately being slowed down to 2G level.

6. The fundamental rights to education, health care, economic opportunities and a decent standard of living, privacy, and justice have been snatched from the people of Kashmir. Since August 5, 2019, the people of Kashmir were kept under lock down to prevent them from freely expressing their opposition to the status of the region. Thousands were jailed, tortured, and many hundreds remain in detention. Further, the brutalities and rights violations perpetrated on the people of Kashmir by state forces and institutions through the protracted conflict have included the enforcement of impunity laws, sexualized violence, torture, enforced disappearances, criminalization of local resistance for self-determination, extrajudicial executions and the burial of civilians in unknown and mass graves.

7. While the Indian government touted to the world that the changes made to the territory will usher in a period of development, prosperity, and job growth, the reality is that in India’s efforts at creating demographic change, Kashmir’s economy has been totally destroyed while India carries out its well-designed policies of economic extraction, land grab, and deforestation.

8. While non-natives are being welcomed to Jammu and Kashmir and given rights to settle there, the Indian government passed another law to bar Muslim migrants of Jammu and Kashmir from returning to their homeland.

The proposed extension of domicile rights to Indian citizens is precisely an action aimed at depriving peoples of Jammu and Kashmir of their integrity as distinct peoples, and of their cultural values or ethnic identities.

We urge you to intervene in the tragedy in Jammu and Kashmir which continues to unfold to the extreme detriment of the indigenous peoples of the region and their basic human rights. At a particularly fragile and fraught time in world affairs, India’s ongoing militarism, state violence, denial of people’s fundamental rights, suppression of information and denial of international access to Jammu and Kashmir only serve to exacerbate and make more precarious what is an explosive, potentially uncontrollable situation in “normal” times. The United Nations Security Council must not fail to uphold its principled commitments regarding Jammu and Kashmir at this critical time and must reiterate its position and remind the relevant state parties of their commitments and obligations.

The peoples of Jammu and Kashmir face grave and immediate threats after decades of state violence, denial of rights, massive human rights violations and the silent inaction of the international community. That tragedy is now fast-moving toward a situation of forced demographic change. In the absence of international attention and action, it is of grave concern that the role of the state forces will be further expanded during the Covid-19 emergency and in the enforcement of the new domicile law.

In the interests of the peoples of Jammu and Kashmir and international peace and stability, you must act now.

Sincerely,

Kashmir Scholars Consultative and Action Network

~

The letter has been signed/endorsed by:

Dean Accardi, Assistant Professor of History, Connecticut College, USA

Raja Qaiser Ahmad, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan

Binish Ahmed, Ph.D. Candidate, Ryerson University, Toronto, Canada

Omer Aijazi, Postdoctoral Fellow, University of Toronto, Canada

Dibyesh Anand, Professor of International Relations, University of Westminster, UK

Mirza Saaib Beg, Lawyer, London, UK

Mona Bhan, Associate Professor of Anthropology and Ford Maxwell Professor of South Asian Studies, Syracuse University, USA

Emma Brännlund, Senior Lecturer in Politics and International Relations, University of the West of England (UWE Bristol), UK

Farhan Mujahid Chak, Associate Professor, Qatar University, Qatar

Angana Chatterji, Center for Race and Gender, University of California, Berkeley

Huma Dar, Adjunct Professor, California College of the Arts, USA

Haley Duschinski, Associate Professor, Ohio University, USA

Iffat Fatima, Filmmaker, India

Mohammed Tahir Ganie, Assistant Professor, School of Law and Government, Dublin City University, Ireland

Javaid Hayat Khan, Ph. D. Independent Researcher and Analyst, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

Serena Hussain, Associate Professor, Coventry University, UK

Khushdeep Kaur, Ph.D. Candidate, Temple University, USA

Shrimoyee Nandini Ghosh, Lawyer and Legal Researcher, India

Mohamad Junaid, Assistant Professor, Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts, USA

Hafsa Kanjwal, Assistant Professor of History, Lafayette College, USA

Fathima Kanth, Ph.D. Candidate, University of California, San Diego, USA

Ain Ul Khair, Ph.D. Candidate, International Relations, Central European University, Hungary

Nitasha Kaul, Associate Professor, University of Westminster, UK

Suvir Kaul, A.M. Rosenthal Professor, Department of English, University of Pennsylvania, USA

Zunaira Komal, Ph.D. Candidate, University of California, Davis, USA

Fozia Nazir Lone, Associate Professor of International Law, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Laura Lucia Notaro, Consultant, Sustainable Development, Milan, Italy

Inshah Malik, Assistant Professor, Kardan University, Kabul, Afghanistan

Umar Lateef Misgar, Freelance journalist, Ph.D. candidate, University of Westminster, UK

Deepti Misri, Associate Professor, University of Colorado, Boulder, USA

Preetika Nanda, Research Scholar, India

Immad Nazir, Research Scholar, University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany

Goldie Osuri, Associate Professor, University of Warwick, UK

Idrisa Pandit, Independent Scholar, Waterloo, Canada

Samina Raja, Professor, University of Buffalo, USA

Iffat Rashid, Ph.D. candidate, University of Oxford, UK

Torrun Arnsten Sajjad, Department of Community Medicine and Global Health, University of Oslo, Norway

Mehroosh Tak, Lecturer, Royal Veterinary College, London, UK

Nishita Trisal, Ph.D. Candidate, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, USA

Saiba Varma, Assistant Professor, University of California, San Diego, USA

Vincent Wong, Faculty of Law, University of Toronto, Canada

Waseem Yaqoob, Lecturer, School of History, Queen Mary, University of London, UK

Anam Zakaria, Author and Oral historian, University of Toronto, Canada

Haris Zargar, Ph.D. Candidate, International Institute of Social Sciences, The Hague, Netherlands

Ather Zia, Assistant Professor, University of Northern Colorado, USA