Letters from Palestine: One by one, we may all fade away, but the martyrs will remain—still, silent, beloved of God

This is the latest from our series on life in the ongoing Israeli genocide. These are stories of survival and resistance in the face of a violence long deranged, narrated through the extraordinary grace of the people of Palestine.

I asked myself the same question every single day. How does a procession keep walking as it carries on its shoulders a life that has ended?

Daily, the cries of grieving mothers sliced through my thoughts. I found myself in tears each time I rushed to the window, hoping for a final glimpse of goodbye.

The air was unusually still. I was in my room—alone, as usual—listening to the endless footsteps echoing through the corridors of Indonesian Hospital, a place too familiar with the weight of death. My window opened directly to the front gate of the main medical center of northern Gaza. Then, a soft knock at the door.

It was my seven-year-old niece. She stepped in with a flower in her hand. She gave me the flower, kissed my cheek, and said, “Just like you love flowers, I love you.”

Something inside me swelled. In that fleeting moment, there was warmth—gentleness blooming in the middle of everything harsh. My heart ached for the love trapped inside us here, for the fragile innocence of children who still managed to breathe through the clouds of smoke and rubble. I ached for her. I ached for us all. And yet the moment didn’t last. Even the smallest piece of peace slipped away before it was fully lived.

Out of nowhere, the whistle of a rocket pierced through the air—sharp, high, and terrifyingly close. A second later, the ground shook with the force of the explosion. I grabbed my niece and tucked her beneath the table. Then I ran to the window—the one facing the gate of the hospital.

Smoke rose. The hill across from us—the one called Qleibo—was disappearing in dust and debris. A home, seconds ago alive with memory, was now a crater.

In two minutes, the ambulances came, carrying what was left of fragile lives. Four minutes later, a crowd emerged, rushing a body through the gate. I saw a boy—just a boy—screaming, “Wait! Don’t leave!” No one heard. No one looked back. They didn’t even see him.

He dropped to the ground and pulled the shrouded body to his chest, the white cloth between them like a final veil. Everything went quiet. Then his cry tore through the silence—not loud, not angry, just broken. A grief too deep for sound.

How could his voice bear itself? How could his mind make peace with the truth—that the person he was sitting with only seven minutes before was now gone, forever?

He couldn’t have understood it. Not yet. Not until grief became his only constant. He’d cry every day. As I do.

We may cry for the whole aching country. One by one, we may all fade away.

But the martyr will remain—still, silent, and beloved of God.

I shut the window and sat quietly, trying to piece together what had just happened.

It’s not that I’m fond of remembering—maybe it’s more accurate to say I refuse to forget. Grief has blurred so much, and the tears have washed away details, but nothing erases like occupation. For it fears memory. It fears the written word. It fears a people hungry for freedom.

History, however, does not forget. It records. It speaks. It remembers how the idea was tried to be assassinated with the killing of Palestinian cartoonist Naji al-Ali, and how the written word became too dangerous when Ghassan Kanafani the brilliant writer was taken.

One line from Kanafani’s final novel, A World Not Ours, echoes in my mind: “Death is not the concern of the dead. It is the concern of the living.”

I’d written it out, bold and clear, and placed it where I could see it day and night. I kept asking: what is death, really? And what burden does it leave on those who stay behind, holding love in one hand and memory in the other? Most of all—what does it mean to live through someone else’s final moment?

And after wandering through a flood of memories—both conscious and buried—I realized something quietly terrifying: that death, when it approaches, can be elegant. Strangely elegant. Almost as if it comes dressed in a style of its own, clean and exact, without noise or smudge.

And I wanted to choose that moment. My elegant moment. With full awareness and on my own terms—if such a thing was even possible here. If I must die, I didn’t want my body torn apart, even if I didn’t feel it. I wanted to be buried whole. I didn’t want the world to mishandle what was left of me. I didn’t want to suffocate under the ruins of my home. I didn’t want to witness everyone’s final goodbye and be the last to leave. I didn’t want to be consumed by helplessness or paralyzed by fear. I didn’t want to leave behind sorrow. I didn’t want to vanish as if I had never been.

But somewhere deep inside, I knew: I didn’t want to die. Not yet. Not before I’d lived long enough to see a real ending. Not before I’d tasted something that resembled an ordinary life—one that still carried peace and love.

Then, and only then, would I choose the most graceful goodbye.

Every single day, I found myself asking—why was all this happening, to us, right here?

Why did we keep condemning the noise, pleading for the night to end, even when no dawn seemed to come?

People like us may fade from the morning light, but never from hope.

Let the world give us hope, not wasted time. Let it heal these cracked roads etched deep into our lives—roads that have become barriers of humiliation, whether for forced exile or so-called “humanitarian aid.”

If only someone had warned us how brutal this path would be, maybe we wouldn’t have charged ahead so blindly.

If we’d known we’d one day witness the occupier’s flag waving over a mountain of broken bodies, we wouldn’t have carried peace like a fragile prayer in our pockets.

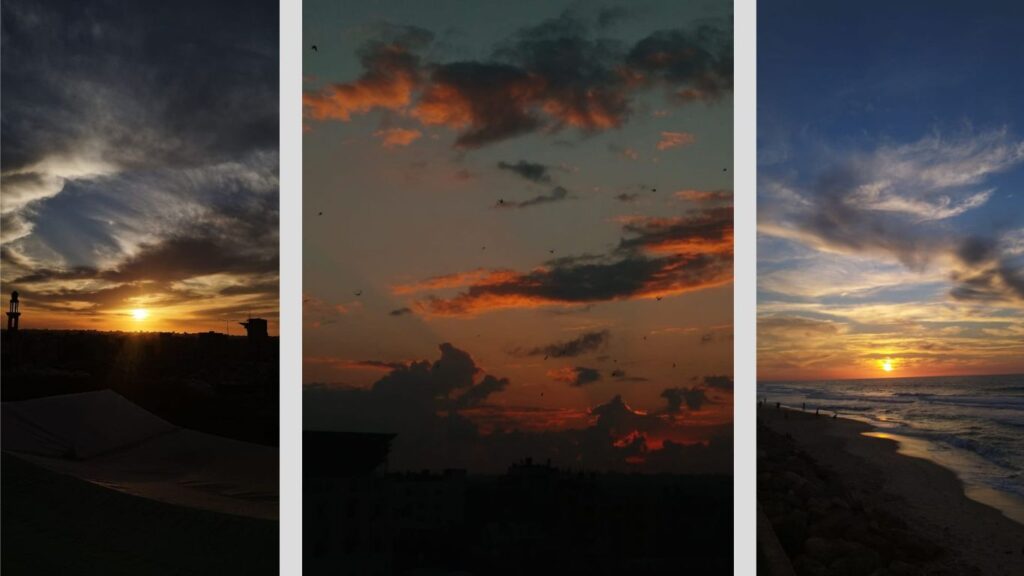

The days stretch endlessly now—so much that even the sun seems lost, its shadows nowhere to be found.

No one even meets their own shadow anymore.

No one dares to look another in the eye, scared to see the brokenness reflected.

We have all become mirrors to one another—worn down by grief, hollowed by history, stripped even of our names.

Names no longer matter.

Are we displaced? Refugees?

Or are we just flames, choking on our own smoke?

I fight with everything inside me to keep hope alive—the hope of coming home. I battle death with hope, with prayer, with the act of writing.

I fill my journal with every moment, sparking a flame that refuses to die—a sudden fire that takes hold and won’t let go.

The spark that led me to the truth, to myself: where I was, how the ground beneath me shifted until I found myself here—a tent roof instead of the open sky and its clouds.

Dear me, I’m writing to you, in a silence that fills everything but my mind.

Anger draws a bitter smile across my face—or maybe it’s just sadness—I can’t tell.

I feel such deep sorrow for you. How did you get used to this road back?

You’ve lost every street, walked every path, and realized none of them lead home—none bring you back to yourself.

All roads lead away, how did you learn to keep going?

How did your feet carry you toward a tent, or a broken dream, and call it refuge?

I write carefully, choosing each word before it reaches you. I won’t be too harsh—there’s already enough weight inside you. I’ll be gentle, just enough—because my heart doesn’t have much love left to give.

Dear one, I write to you now carrying the sorrow of those scattered far from home, and the hopes of those waiting at life’s crossroads.

May you read this safe and surrounded by your own, your spirit calm and your eyes at peace with those who hold you close.

May you find the refuge you’ve been searching for.

Editor’s note: The text was lightly edited for clarity while the images were published unaltered since Sawsan Al-Ajjouri shared them with The Polis Project. We hope it helps preserve the integrity of storytelling in the context of living through and bearing witness to the ongoing genocide. Al-Ajjouri remained out of touch for over two months, recovering from injuries sustained in the Israeli attacks. At the time of publishing, she was “too weak to bear the constant coughing, unable to breathe the heavily polluted air in an area burned by the bombing.” As Israel’s genocidal violence rages on, she—along with countless others—remains acutely short of food and medicines. In pictures: top, Essam, Al-Ajjouri’s seven-year-old niece; above, Al-Ajjouri. Photos by Sawsan Al-Ajjouri.