Manipur’s long wait for justice: Remembering 1,528 cases and the murder of Thangjam Manorama

While remembering and reconstructing the gruesome case of the extrajudicial killing of Thangjam Manorama Devi in 2004, Arijit Sen looks at the consequences of the draconian application of AFSPA in Manipur. The article also highlight the relentless struggle for justice of the families of the victims of indiscriminate State violence.

In the dead of night, Khumanleimai Devi often sees Thangjam Manorama Devi, her dead – murdered – daughter.

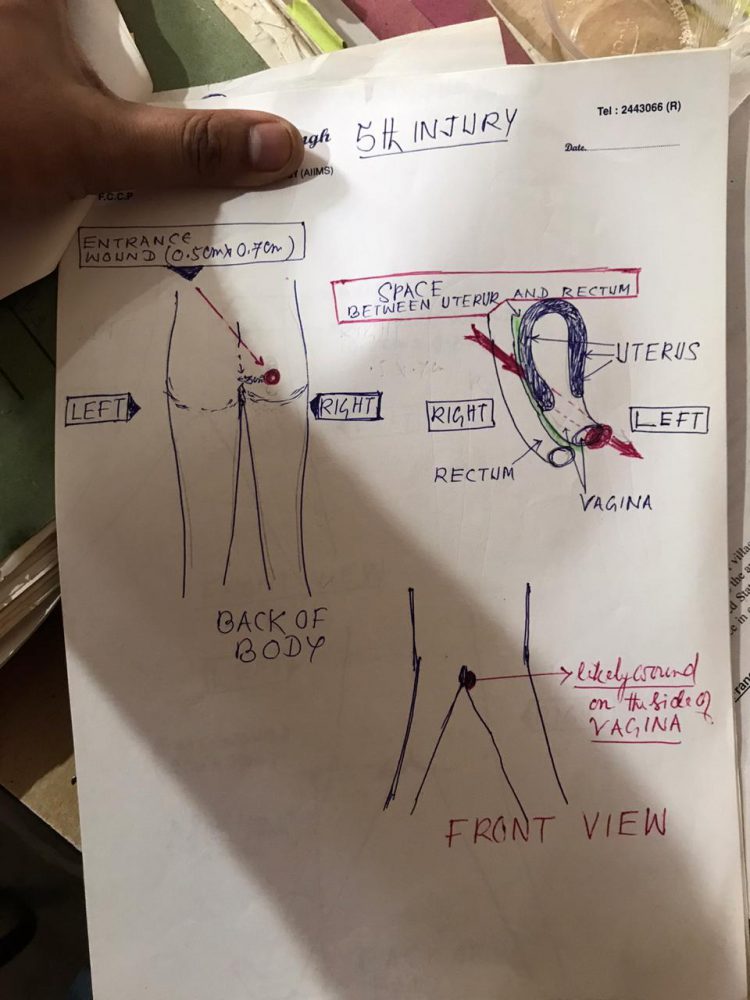

Manorama would have turned 49 this year. She died in July 2004 in Manipur, away in India’s Northeast. At night. Then a 32-year-old woman, she was overpowered, waterboarded, dragged out of her house, and tortured by at least 13 members of the Indian security forces. She was then shot dead. All on suspicion of being an operative of an underground militant outfit. No one bothered to prove her guilt. There was human semen on her clothes when her dead body was found. There were bullet wounds in her vagina.

It remains one the most gruesome staged encounter killings in India’s history. It has also been forgotten, bar a monetary compensation decided in Court.

“There are many reasons to recall and remember Manorama’s murder in 2020,” Babloo Loitongbam of Human Rights Alert (HRA), a human rights group in Imphal, says. Loitongbam echoes what I’ve heard from Manorama’s family before. Justice has not been delivered. The perpetrators are still at large. He reminds me that the people’s protest after the killing of Manorama was unprecedented. “They not only mobilized the people of Manipur but went way beyond it. And it still remains a reminder to the people that we need to be going together and resist injustice. It is relevant in every sense.”

Manorama’s murder was the turning point in the fight against extrajudicial encounters in Manipur, where the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA) has been in effect since 1980. In 2004, during the widespread protests, a coalition of Manipuri civil society organizations called Apunba Lup met the then Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh in Delhi. The Jeevan Reddy Committee was consequently set up to review AFSPA and asked for a repeal of the Act. Yet nothing changed.

AFSPA, an extension of the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Ordinance of 1942 used by the British to control freedom movement, was introduced in the Naga Hills in 1958 as a temporary measure to mitigate armed conflict. When the Bill was debated in the Indian Parliament, Laishram Achaw Singh, a Member of Parliament from the region, dubbed it as a lawless law. “This piece of legislation,” he had said, “is an anti-democratic measure and also a reactionary one.” Since AFSPA was introduced in Naga Hills and later in Manipur and then in Jammu and Kashmir in 1990, there have been a large number of civilian deaths and human rights violations including enforced disappearances, torture in custody and extrajudicial executions. Individuals opposed to the State’s narrative of governance and development have been systematically victimized, tortured, brutalized by the Armed Forces. AFSPA is still in use in India’s Northeast: in most of Manipur, parts of Nagaland, Assam and Arunachal Pradesh.

*

Manipur was an independent kingdom and came under British rule in 1891 as a Princely State after the first Anglo-Manipur War. In 1949, Manipur merged with India with a treaty of accession. In the run up to it, the king was summoned by the Indian Home Minister and was “warned in no uncertain terms,” as documented by Bertil Lintner in his book Great Game East—India, China and the Struggle for Asia’s Most Volatile Frontier, not to think of any other alternative thereby raising suspicions of having been coerced into signing. The opposition to the integration with India came from ordinary Manipuris and not from the monarchy. Attempts to undermine the monarchy and, according to some accounts, later oppose India came from Hijam Irabot in collaboration with the Communist Party of Burma, just across the border. It was in 1964, fifteen years after the merger, that Manipur started witnessing a violent anti-India resistance that began with the formation of the United National Liberation Front (UNLF).

As different resistance groups emerged and violence continued, Manipur was declared a “disturbed area.” In 1980, AFSPA was imposed on the entire state after being used sporadically. Despite an elected government and an electoral process that witnesses a voter turnout of 80% or more, security remains fragile in Manipur. The constant application of AFSPA has led to a de facto militarization of Manipur and other northeastern States of India. In 2006, after a visit to Manipur, Henry V. Jardine, US Consul General, Calcutta, mentioned in a secret cable to Washington that “the general use of AFSPA meant that the Manipuris did not have the same rights of other Indian citizens and restrictions on travel to the state added to a sense of isolation and separation from rest of India ‘proper’.”

In 2020, sixteen years after the murder of Manorama, things are slowly changing in Manipur. “The police behavior has changed substantially,” Loitongbam tells me. Working on extrajudicial executions for more than two decades now, he thinks that such executions have stopped: a huge change from the past. And yet there are deep traces of violence and no sense of closure for many families that suffered atrocities under AFSPA. Manipur still remains a heavily militarized area and, as many activists point out, the military is still not part of the accountability process.

“Maybe the way the State watches citizens have morphed into something else now,” says filmmaker Bachaspatimayum Sunzu. In 2004, it was Sunzu who had gone inside the mortuary at the Regional Institute of Medical Sciences, Imphal, where the dead body of Manorama lay for autopsy. “I went in,” Sunzu recalls, “and I focused my camera on her body and let the film roll because the world had to know about Manorama’s story.” This would lead to the documentary AFSPA 1958, made by Sunzu and Haobam Paban Kumar.

“Now, it is a different kind of surveillance. The violence is a different kind of violence. It is probably in step with the politics of a new India that has no space for dissent,” Sunzu says.

In the first four months of 2020, 13 activists were arrested by the Manipur Police for their social media posts. The space for dissent is being erased systematically in the State, yet civil society remains vibrant. There are many groupsthat have been resisting erasure, violence by security forces and injustice with their documentation, petitions, neighborhood pickets, marches and road blockades.

The Extrajudicial Execution Victims Family Members (EEVFAM) is a collective fighting for justice since 2009. EEVFAM, along with Human Rights Alert, filed a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) in 2012 to the Supreme Court mentioning that 1,528 civilians, including 98 children, have been killed in Manipur between 1979 and 2012. All the deaths were cold-blooded murders —extrajudicial executions, the petition claimed. The search for justice by Manorama’s family is part of this collective struggle.

“We are waiting, waiting, waiting for justice. Only the killing has stopped now. But threats, intimidation, torture continue. They always find ways to do such gruesome things,” Renu Takhellambam, who heads EEVFAM, says. “For what Manipur has witnessed and I have witnessed, it is too early to say that things have changed because the killings have stopped. Where is the justice for the 1,528 families?”

Takhellambam lost her husband to an extrajudicial encounter on 6 April 2007. The Police inspector accused of killing her husband received a gallantry award. Since 2009, with Edina, Ranjita and a group of other women – mostly mothers, wives and sisters of those who were killed in encounters – along with Human Rights Alert, Takhellambam has been pushing for justice and trying to ensure that EEVFAM’s voice is heard across India and beyond.

The fight, she feels, is becoming more difficult now because the legal process has slowed down. There has been no movement in the Courts: the last time EEVFAM’s petition was heard was in September 2018, she says. There were two judges hearing the case; no new judge or new bench has been constituted after the retirement of one of the judges in December 2018. “It has been two years now since the case was last heard,” Loitongbam says.

“We can see that things are slowing down. There is probably a design to how EEVFAM’s quest for justice is being pushed back. And since violence has reduced in Manipur, the world might just start thinking things are better. Everyone [but us] has forgotten about the absence of justice, of closure,” adds Takhellambam.

In July 2020, at the 44th United Nations Human Rights Council session in Geneva, Edmund Rice International (ERI) — a nongovernmental organization with a consultative status — raised this issue. Brian Bond from ERI read a statement drawing attention to the inordinate delay in the delivery of justice to the victims of extrajudicial executions. Exactly two years before this, on 4 July 2018, Agnes Callamard, United Nations Special Rapporteur for Summary, Arbitrary and Extrajudicial Executions, and Michael Forst, United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights Defenders, expressed concern about the delay of investigations by India’s Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) on the 1,528 cases mentioned in the PIL. The Rapporteurs observed that the delay was “deliberate, undue and unreasonable.” By the end of July 2018, Supreme Court judges Madan Lokur and Uday Lalit, asked the then CBI Director to decide whether to arrest the 14 army officers accused of murder in 41 of the 1,528 cases. The same bench in September 2018 constituted a Special Investigation Team (SIT) under the CBI for timely framing of chargesheets against the Army and Police involved in extrajudicial executions – known as “fake encounters” in Manipur. Nothing came of that and in July 2020 EEVFAM asked to establish Special CBI Courts in Manipur in a bid to accelerate the process of justice.

*

The PIL that EEVFAM and HRA filed in 2012 brought a ray of hope: in 2013, after EEVFAM’s petition, a Supreme Court-appointed committee reached Manipur. The committee’s inquiry into six cases from the list of 1,528, found that seven deaths in the six cases were the result of extrajudicial executions. None of the victims had any criminal or insurgency-related record to be pursued as a suspect; among the dead was Azad Khan, a 12-year-old boy. AFSPA made “a mockery of law,” the committee said in April. Just four months earlier, the Verma Committee on Amendments to Criminal Law, formed after the 2012 Delhi gang-rape (in which a 23-year-old woman was tortured, raped and killed on a moving bus), found that AFSPA legitimized sexual violence. By December 2014, more than ten years after she was killed, the Supreme Court ordered an interim compensation of 1 million Rupees to Manorama’s family.

In 2016 the Court, while listening to the EEVFAM petition, made a landmark ruling by removing the cloak of immunity that AFSPA offered to the security forces through Section 4A of the Act. This Section allows “any commissioned officer, warrant officer, non-commissioned officer or any other person of equivalent rank in the armed forces […] after giving such due warning as he may consider necessary, fire upon or otherwise use force, even to the causing of death.” In effect, this Section legitimizes the use of force if and when a member of the armed forces deems it necessary and violates the right to life as enshrined in Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. When the Supreme Court stated that “If any death was unjustified, there is no blanket immunity available to the perpetrator(s) of the offence,” it breathed life into a struggle for justice going on for years in Manipur. Amicus curae Dr Menaka Gurusamy’s report on human rights violations by Armed Forces played a key role in the Court proceedings. Her written submission underlined that the Constitution never permits violation of Article 21 and if court martial proceedings result in denial of fundamental rights, Courts can ask for a judicial review.

In a 2017 hearing of the same PIL, the Court went a step ahead by requesting that First Information Reports must be lodged against those Army men for carrying out operations in Manipur and across the country. As the wheels of justice moved, more than 300 Army personnel challenged the order in August 2018. By November 2018, the Court dismissedthe Army petition. Since then, however, everything has stopped. According to Loitongbam, there are some positive outcomes from the judgments of Justice Madan Lokur before he retired: “Chargesheets have been filed and policemen indicted.” However, he also points out that not a single member of the Armed Forces of the Indian Union has been indicted.

*

In 2019, I visited Manorama’s house, as I had done often between 2006 and 2014 when I was based in Assam. “Khumanleimai has nightmares whenever she falls sick,” Soniya tells me about her mother -in-law, Manorama’s mother. She could barely make out the words, but it sounded like a wail. “An old woman crying for her daughter in the middle of her sleep. Once, after what could have been a nightmare, she told me that she saw Manorama sitting by her side. I tried to console her by saying that it was maybe because she was unwell that she thought her daughter was back.” The hallucinations started almost immediately after the murder, according to Dolendro, Manorama’s brother: “She hallucinates and screams, Mono, Mono, Mono… lakey, lakey, lakey (Manorama… she is coming).” Medications haven’t helped her forget the loss of her only daughter, the doctor’s prescription mentions “sad feeling” and “sleep disturbance,” but it is much more than that.

There have been attempts to share her sorrow and EEVFAM has been part of the process. In 2013, Khumanleimai stepped out of her house to meet Rashida Manjoo, the United Nations Special Rapporteur for Violence Against Women, its Causes and Consequences. A meeting was held with many mothers who have lost their children to State violence in an attempt to provide some kind of closure. The mothers hoped that Manjoo’s report to the United Nations Human Rights Council would accelerate justice.

The meeting with Manjoo was the last big public event for which Khumanleimai went out of her house. Manorama’s family members prefer to avoid talking about her as it invariably leads to depression, crying and a reminder of the void she has left behind. In silence, Manorama now stays in their memory and in a few faded and enlarged photos. Last time we met, Manorama’s mother spoke somewhat incoherently, in disjointed sentences. She began with: “Moina hairiba aduga chaap mana ray (Whatever they say, I don’t have anything to add),” but then added: “I suffocate when I talk about this.” And then, after a pause: “I would be happy if the killers are punished.”

Between 1996 and 2007, Justice Chungkham Upendra Singh oversaw inquiries into at least twelve cases of extrajudicial executions, including Manorama’s. He was clear that security men allegedly involved in murders or rapes should be arrested and put in jail. “Suspended, suspended, what suspended?!,” I remember him shouting in anger during a conversation on fake encounters in Manipur when I had asked if the security forces who have allegedly killed civilians should be suspended. For him a mere suspension meant nothing. He died in 2015.

The Manorama Inquiry Commission headed by Justice Upendra was met with non-cooperation and much resistance from the Indian paramilitary forces. The commission had called Manorama’s murder as “one of the most shocking custodial killing of a Manipuri village girl” – as was revealed when the Upendra report was handed over to the Supreme Court in 2014, ten years after Manorama’s death. A 2008 Human Rights Watch report also alleged that an Army Major and four others had been accused in the killing during the Army Court inquiry. Not a whiff of information about what action was taken by the Army has come out yet. Earlier, the Armed Forces took recourse to AFSPA and filed a writ petition before the Guwahati High Court challenging the authority of a state-government appointed commission. The High Court had said in 2005 that the Manipur Government didn’t “have administrative control over armed forces entitled to protection” under AFSPA. By September 2010, the Guwahati High Court asked the Manipur government to act on the Upendra inquiry report.

The publicly available report clearly states that Manorama was tortured and murdered. Some documents shared with the Court by lawyers representing Manorama’s family also show how Manorama was shot at. In 2004, once the news of Manorama’s death spread, Manipur erupted in protest. Two days later, twelve Imas (mothers) disrobed and held banners made of white cloth with protest messages written in red paint that read: “Indian Army Rape Us” and “Take Our Flesh.” These brave women stood in front of the Kangla Fort, the Indian paramilitary headquarters in Imphal, protesting Manorama’s murder and resisting State violence with their bare bodies. Four years later, in December 2008, on a cold Delhi morning, I met the Imas. This time they were sitting in Jantar Mantar, a public square in Delhi, and asking for AFSPA to be repealed. In 2020, those among them who are still alive, continue to resist and protest in different ways; the stranglehold of AFSPA, however, remains untouched.

“AFSPA breathing normally is unfortunate in more ways than one,” says human rights activist Onil Khsetrimayum. According to him, it is worth to continue remembering the brutal details of Manorama’s case as well as those of every case documented by human rights activists in Manipur. “The resilience of each and every family, the protests carried out against a powerful State machinery, the Imas coming together every single time, is something all of us should remember. Other than Kashmir, I don’t know where else does this happens.”

Edina Ningthaujam, a founding member of EEVFAM, belongs to one of the families protesting against State atrocities in Manipur. Her husband, says Ningthaujam, was framed and killed in an encounter by the paramilitary forces and Manipur police. This year she lost her mother-in-law. “My mother-in-law was tired of waiting for justice. She always told me that she wanted to meet the Police personnel who killed her son, slap them and even take revenge”

*

Manorama’s death galvanized and brought together Manipuris from different backgrounds in the fight for justice. In 2019, I met Nene Anandi in Imphal. A retired physics teacher at a local school, Nene was one of the brains behind the iconic protest after Manorama’s murder. There were three Imas who had gone to the Regional Institute of Medical Sciences the night after Manorama was killed. According to Ima Momon, one of the protestors who was there with Ima Soro and Ima Nganbi, they felt it was pointless to be alive after they caught a glimpse of Manorama’s dead body. That July morning in 2004, twelve women got together in anger and made history as they held their protest banners. These twelve brave mothers – Gyaneshwari, Taruni, Tombi, Mema, Soro, Ramani, Nganbi, Jamini, Momon, Ibemhal, Ibetomi and Jibanmala – were jailed for three months. Manipur continued to burn in protests. One month later, on India’s Independence Day, a 28-year-old Manipuri man, Pebam Chittaranjan attempted self-immolation in a town called Bishenpur, demanding the withdrawal of AFSPA from Manipur. He succumbed to his burn injuries a day later. Chittaranjan’s mother, whom I met in 2012, still hoped that her son’s sacrifice would not go in vain.

In recent years, electoral politics in Manipur has witnessed a change in government and yet electoral promises by politicians to look into “fake encounters” and push for justice have been to no avail. In 2020, after more than forty years of a law that has wreaked havoc in the lives of people and has sadly become a part of everyday existence, Manipur still remains under AFSPA. Last time I left Manorama’s house, her brother Dolendro said: “Justice is when the killers of my sister are brought to the Court of law and given appropriate punishment under the Law.”

In this long fight both Loitongbam and Takhellambam agree: many parents who have been fighting for their loved and lost one have died without seeing justice because of the inordinate delay in the process. Perhaps this is one reason Khumanleimai Devi still sees Manorama at night. There has been no closure, and probably there won’t be any in the near future. Not just for Manorama, but for all those who were killed in extrajudicial executions in Manipur.