Mass displacement looms in Indian hill state as govt pushes INR 62-billion expressway through riverside slums

Shadows of displacement loom large over densely populated, working-class neighborhoods in the only cosmopolitan city in India’s northwestern Himalayan state of Uttarakhand. A few thousand families across the city now face an unsettling reality: their homes may soon disappear beneath an elevated expressway.

A new road project is coming up in the area. It involves the construction of two elevated corridors, one 15 kilometers and the other 11 kilometers in length, over the Rispana and the Bindal rivers, tributaries of the Ganges. With an estimated cost of around INR 6,200 crore (62 billion), the road project is ostensibly aimed at easing traffic congestion in Dehradun, the winter capital of Uttarakhand.

“The very thought of that massive expressway coming up right above our demolished neighborhood terrifies me,” said 10th-grade student Deepak, whose father works as a daily-wage laborer, as he stood amid the winding lanes of Kandoli, one of the settlements that may not exist much longer.

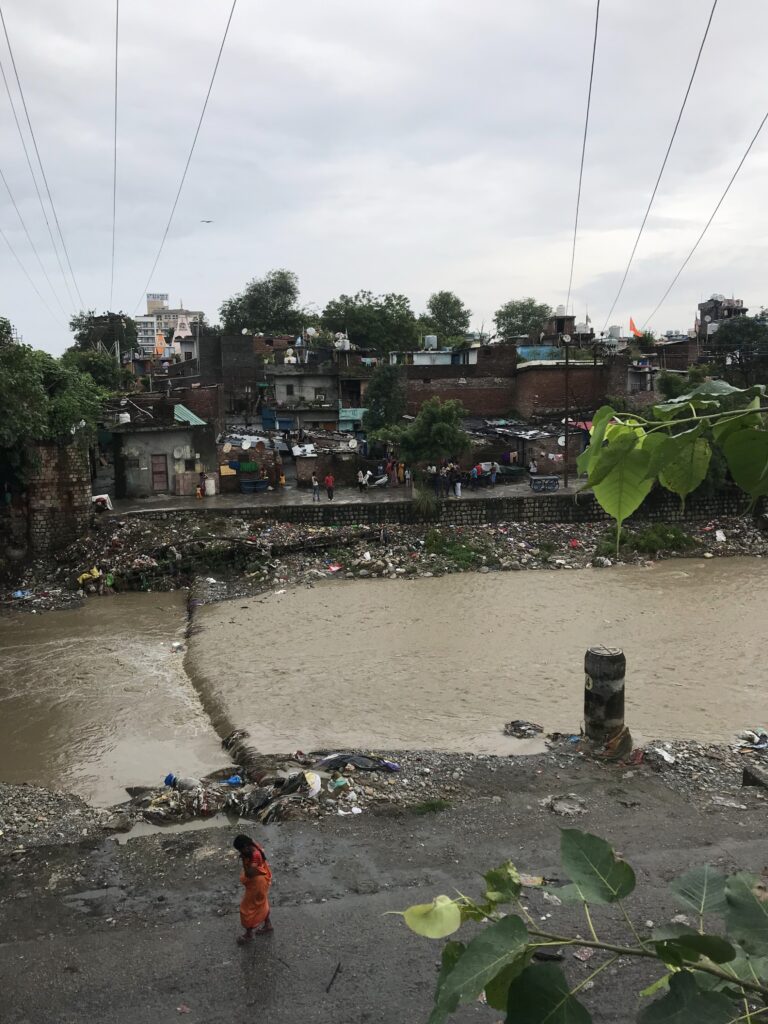

In ghetto after ghetto, cramped old houses stand cheek by jowl along the banks of Rispana and Bindal, the two main riverine beds that cut across the state capital. Thousands of income-insecure, working-class households, sheltered behind thin walls for decades, are slated to be rendered homeless.

Women residents of the area, led by Mumtaz, Pragati, and Saeeda, had gathered last month in the community’s only open space in Kandoli to discuss their concerns. Their anxiety was palpable as the women narrated how the demarcation process for the demolition was secretly initiated. In urgency, Mumtaz had called Shankar Gopal, who heads Chetna Aandolan, a voluntary collective of activists helping out the working-class women of Kandoli through small-scale enterprises, and unionising male daily wage labourers. The women showed the activists and this reporter the markings made by a team of contract workers and their supervisors on the building walls and the floors of lanes.

Pragati said those who had come to do the markings refused to disclose what the markings were about. Saeeda claimed she was able to speak to one of the “helpers” separately and found out that the marking exercise was part of the demolition plan for the elevated roads project. The locals then formed a consensus after holding an impromptu meeting and decided to resist the demolition plans as a united front. They also proposed organising a mass demonstration against the project soon.

Short cement columns have been planted near houses marked for demolition, along with markings on walls and floors showing the extent of bulldozing planned along the river banks.

The first signs of the ambitious Rispana-Bindal elevated road project emerged when the marking exercises were swiftly completed within a week across settlements spanning 10-15 kilometers along both riverbanks. In late July, state authorities announced a schedule of “public hearings” for affected neighborhoods; they were, at the time of publishing, processing six to eight neighborhoods at a time, all likely to be completed within the first two weeks of August. These hearings fulfill preliminary procedural requirements for government acquisition and demolition of properties, but are increasingly being seen as indiscreet attempts to subdue the resistance through outright bargaining.

However, the project details and assessments of social and environmental impacts have not been shared beyond a restricted circle of officials. This has made the prospect of free, prior, and informed consent among the affected communities appear questionable.

The proposed infrastructure will extend the nearly complete 210-kilometer expressway connecting Delhi to the base of the Mussoorie hills, straight through the Dehradun valley, transforming this tourist gateway for India’s growing class of car-owning vacationers. However, there are serious concerns around the limited carrying capacity of the Mussoorie hills; it is a prime tourist destination in Dehradun district, and a single hill road goes up to it from the northern tip of the valley, where Dehradun city ends. On the other hand, for the families of Kandoli and all the other affected localities, this symbol of infrastructure development threatens to erase the only home they have known ever since they migrated.

These people possess ration cards, electricity and water connections, voter IDs, and house tax receipts for their current address, but no legal documents to prove ownership of the houses and land they inhabit. Further, the municipal corporation has reportedly stated that house tax receipts would not be considered valid proof of ownership. Despite not having legally admissible ownership documents, they claim they have paid a handsome price for their habitat to touts akin to slumlords.

During the four monsoon months, rivers and brooks swell up in the hill state. However, afterwards, the silt left behind on the rocky beds of Rispana and Bindal appears unsightly as garbage and sewage are lodged over the dry months from October to June. The landless migrant workers, largely from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, and a few from the hills of Uttarakhand, are compelled to house their families amid such unhygienic conditions only to eke out a meagre living. Now, the billion-dollar road plan, currently in its final stages under the aegis of the National Highway Authority of India (NHAI), threatens to uproot them entirely.

Even as the public hearings aimed at striking a bargain, it was still not clear what resettlement and compensation plans, if any, the concerned authorities would offer to the people they plan to displace. Their future remains uncertain.

Broken promises

The road project has gained momentum very recently in Uttarakhand. Officials at the state’s Public Works Department, the nodal agency for the proposed “elevated corridor project,” said they have entrusted a Detailed Project Report to the NHAI for a pre-execution review and final approval.

As the government gets the ball rolling, those living in the riverbank settlements feel betrayed. On January 25, ahead of the urban local body elections in Dehradun, at a public meeting to campaign for the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) mayoral candidate, Chief Minister Pushkar Dhami said, “Not a single house will be demolished.” The meeting was held right next to one such settlement.

The BJP, in power at the state government since 2017, comfortably bagged 63 percent of urban wards as well as the mayoral seat, on the back of sops for those living without regular land and house ownership documents along the riverbanks. A fortnight after the elections, in mid-February, the chief minister “directed to start work soon on the Dehradun Elevated Corridor.”

Thus came the push to initiate the demarcation process for an anticipated mass demolition drive in the settlements, while the Detailed Project Report reached an advanced stage of sanctioning, ahead of fund allotment. According to reports, at least 2,600 households would have to be evicted for the project. The evacuees would number over 10,000, going by this conservative estimate.

“In January, during the poll campaign, Dhami not only assured us [of] residential stability, but actually promised us ownership documents that would authorize our humble dwellings. But now we face this impending demolition. We’re not going to take this betrayal lying down,” said an irate Ashok, one of the slumdwellers who do odd jobs from ironing clothes to gardening. He pledged to fight the project along with others affected by it.

Alongside the demarcation of properties falling in the shadow of the elevated roads project, resistance has also been brewing within the settlements. Small demonstrations have already been held in opposition to the scheme, and a signature campaign against it is underway.

According to Jitendra Tripathi, Executive Engineer at the Public Works Department, who led the team that finalised the new project proposal, the State will oversee the land acquisition and rehabilitation and/or compensation for the evacuees. The NHAI would thereafter construct and maintain the proposed corridors. Accordingly, funds would be allocated partly by the Uttarakhand state and partly by the Union government. The NHAI, as per prevailing norms, would most likely award the contract for building and maintaining these civil engineering structures to corporate bidders interested in investing for anticipated gains from toll plazas along the expressways.

A possible white elephant

Designed for two elevated roads between the southern and the northern fringes of Dehradun, with a total length of just 26 km, the proposed Rispana and Bindal elevated road project’s budget, at 62 billion, is almost half of the total funds (INR 130 billion) for the 210 km expressway from Delhi to Dehradun. The proposed roads aim to carry a heavy influx of vehicular traffic from Delhi to Dehradun, along with the planned extension leading up to the foothills of the Mussoorie hills.

However, the significant daily inflow of passenger car units (p.c.u.) does not take into account the limited carrying capacity of Mussoorie. Anoop Nautiyal, a public policy analyst based in the valley, said, “Mussoorie’s limited carrying capacity of tourists and their cars has compelled the state government to consider regulatory measures, including mandatory registration of incomers. From this alone, it is evident that the four-lane elevated corridor across Dehradun would turn out to be a white elephant.” He further warned of an “immense possibility” of the frequently witnessed traffic congestion on the hill road between Dehradun and Mussoorie, creating “bottlenecks at both ends of the elevated roads.”

Once a quiet sub-Himalayan hill station established for British colonial officers and their families accustomed to colder climes, the overcrowded Mussoorie now attracts more tourists than its roads and approaches can accommodate. According to Tripathi, the elevated corridors will be built at an average height of 15 meters above the river beds or ground level, with a capacity to carry 9,000 p.c.u. per day along the Rispana, and another 11,000 p.c.u. along the Bindal. While a normal-sized passenger car may be assigned a value of 1 p.c.u., a bus or truck would be assigned a value of 3 p.c.u. Each of the elevated roads is expected to have four lanes with a total width of over 20 meters, and a total capacity of carrying as many as 20,000 passenger cars to the base of Mussoorie in a single day.

“What was the point in enhancing vehicular access through an already congested state capital by erecting an elevated expressway?” asks social activist Shankar Gopal. “The hill road winding up to Mussoorie beyond the Doon valley already gets choked up for hours with excess traffic, every other weekend, and more so during the summer and winter vacations.” Providing the means for more cars to reach the base of Mussoorie would cause much greater congestion than ever seen before.

According to Nautiyal and Gopal, instead of this project, the state’s priority should be to manage traffic congestion within Dehradun through public transport schemes, a semblance of which has been proposed in the latest draft master plan, intended to be valid until 2041. The master plan, however, has been left in abeyance since it was drafted two years ago. Every major city in India has an approved master plan for its developmental activities, formulated and supervised by an urban development authority. In 2018, the High Court of Uttarakhand set aside an earlier master plan that was valid until 2025. Since then, the state capital has operated without any officially approved master plan to guide traffic flow within or around the city.

Without a comprehensive development framework, Uttarakhand’s capital has continued with unplanned and arbitrary growth, which began when the state was formed 25 years ago. This haphazard development has now reached a critical point.

In response, the government has proposed elevated roads at the highest levels—ostensibly to manage excessive traffic. However, this expensive solution overlooks more cost-effective, sustainable, and community-friendly alternatives that could better address the problem based on residents’ actual experiences.

A section of the local civil society met Tripathi on June 10, under the auspices of Dehradun Citizen Forum, a collective of the stakeholders, in a bid to apprise the government’s nodal agency of their concerns around factors such as the environmental impact, sustainability and stability of the project, given factors such as landslide propensity, seismicity, and groundwater susceptibilities in the Himalayan terrain. However, this has not yet made any difference to the planned project.

Most importantly, the elevated road proposal would end all hopes of reviving the Rispana and Bindal rivers. A massive tree plantation drive was launched for this revival a few years ago but was abandoned after the change of government before the last Assembly elections, which brought Dhami—then just a legislator—to power.

The proposal involves covering the rivers with concrete elevated roads supported by piers and pillars built in the riverbeds and along the banks. Critics from citizens’ forums and activist groups warn that this would cause severe environmental damage. According to these critics, the construction would harm marine life, block rainwater and groundwater from reaching the rivers, and reduce water flow. This would lead to the accumulation of garbage and sewage in the rivers. The project would also require cutting down more trees and creating an artificial skyline that would permanently alter the natural beauty of the Doon Valley.