Pablo López Alavez – 15 Years in Prison for Defending Forest and Indigenous Territories in Mexico

When I first read about the case of Pablo López Alavez, what struck me was how familiar it felt — an echo of so many others disappeared by the state in India, the United States, Palestine, Sudan, and far beyond. The method is chillingly consistent: a defender of land and people is taken in broad daylight, disappeared into prison, and held for years on fabricated charges. Pablo’s abduction by the Mexican state mirrors the fate of Delhi University Professor G.N. Saibaba, who, like Pablo, was protesting and documenting the corporate–state colonisation and destruction of indigenous homelands.

In tracing the details of Pablo’s case, more names and stories came to mind — human rights defenders, political prisoners, and activists across continents — all targeted under draconian laws, all punished for standing in the way of extraction and power. The patterns are the same: law used as a weapon, trials built on lies, and the grinding machinery of imprisonment meant to crush resistance.

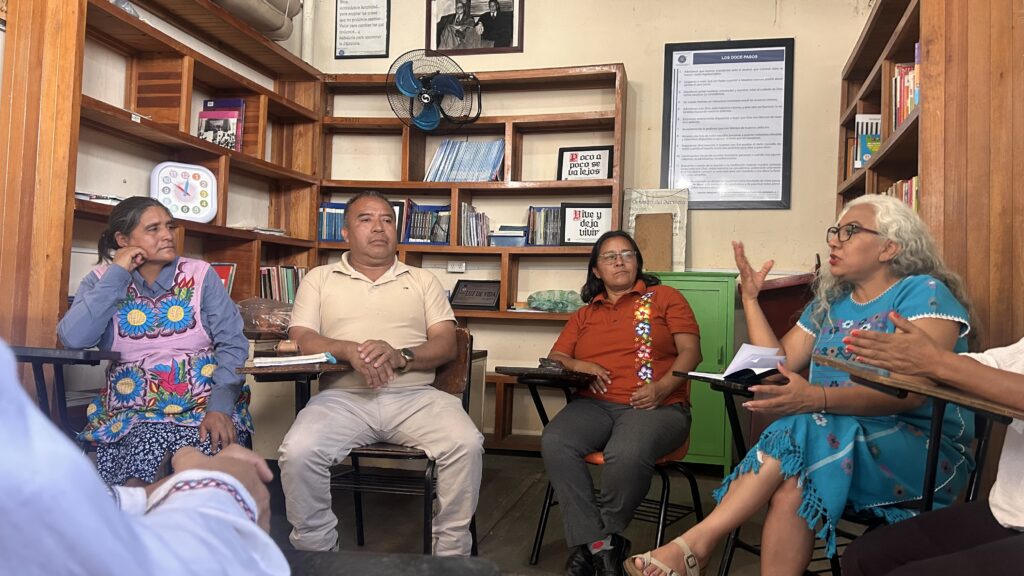

Today, on the fifteenth anniversary of his incarceration, we publish Pablo’s profile, written by The Polis Project’s Suchitra Vijayan in collaboration with Front Line Defenders and Consorcio Oaxaca as part of the Profiles of Dissent. The series began as a way to document India’s political prisoners and defenders, but it has always been about more than one country. It exists to remind us that our struggles are connected — and that the global infrastructures of extraction are inseparable from the dispossession and destruction of Indigenous lands and rights everywhere. These patterns repeat across geographies: disappeared in India, the US, Palestine, Sudan — wherever resistance threatens power.

On 15 August 2010, Pablo López Alavez was driving home with his wife, Yolanda Pérez Cruz, and his grandson in Río Virgen, Ixtlán de Juárez, Oaxaca, México. A red pickup truck cut them off and caused the car to stop. Fifteen men in black, hooded and armed with firearms, came out from the back of the truck. “They put rifles to our heads and told us not to move. The others opened the door and pulled out my husband and grandson,” said Yolanda, herself an environmental defender, while speaking to the Front Line Defenders. Before Pablo could react, the rest of the family had been pinned to the ground. He was then dragged from the driver’s seat, thrown face down into their truck, and driven away. Vehicles were switched several times to cover their tracks. Hours later, when he could finally see, he was surrounded by state police. No arrest warrants had been issued for Pablo, but by nightfall, he was inside Etla prison in Villa de Etla, Oaxaca, around 80 kms from where he was abducted, and accused of a homicide committed three years earlier.

Pablo belongs to the Indigenous Zapotec community from the mountains of Oaxaca and was persecuted for defending his community’s land and water. In 2017, after seven years in pre-trial detention, he was sentenced to 30 years in prison, and the conviction was upheld in 2020.

He has always maintained his innocence, and so has the United Nations, which has twice demanded his immediate release. The Mexican government, however, has never responded to any pleas, petitions or international condemnations. The UN has described his detention as “arbitrary” and the judicial process as riddled with “irregularities and significant violations.” They found the evidence against him to be inconsistent, and noted that the proof of his absence from the crime scene was presented by his defence but ignored by the judge. The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention concluded that “the true reason for Mr. López Alavez’s arrest and prosecution is his work as a human rights defender in his community.” It also documented that he suffered acts of ill-treatment, torture, and threats by prison officials.

The Crime Behind the Crime

Mexico is one of the most dangerous countries in the world for human rights defenders (HRDs). According to Human Rights Watch, in 2023 alone, 18 environmental and land defenders were murdered. In 2024, the HRD Memorial documented the killings of 324 HRDs in 32 countries and found that 32 of these killings occurred in Mexico. Moreover, 79.3% global HRD killings in 2024 corresponded to the Americas. The report also found that land and indigenous rights defenders were particularly vulnerable as they constituted 38.3% of the HRD killings worldwide in 2024.

Defenders in Mexico live under permanent threat of intimidation, fabricated charges, years of pre-trial detention, and disappearances that bear the fingerprints of the state. Those who defend indigenous territories face an additional punishment — their struggle is criminalised, dismantled through the courts, and their bodies disappear into prisons far from the land and communities for whom they fought. At its core, systemic racism shapes the Mexican justice system, designed to strip indigenous peoples of their agency, leaders, identity, and land.

“I don’t regret being a defender of nature. Everything I’ve been doing is for the good of the future of my children and grandchildren, of my community. The water that flows to the town comes from the hill we conserve. Our grandparents protected it; they died, but we arrived. We’re passing through, but our children will remain… If we don’t take care of the forest, everything will collapse,” Pablo said to El País México from prison.

Pablo is one of many indigenous rights defenders targeted through arrests without cause, prolonged imprisonment, and sentences so severe that they become “informal life sentences”. This pattern of criminalisation is tied, thread for thread, to state complicity in corporate plunder of indigenous land. Instead of protecting communities, the state stands as guarantor for corporate extraction, prosecuting those who speak of land theft, and cutting the tongue from the body politic of resistance.

Pablo’s case cannot be separated from the contested geography of Oaxaca. San Isidro Aloápam and its neighbour, San Miguel Aloápam, have been locked in a decades-long dispute over forest lands. San Miguel secured logging permits; San Isidro was denied legal title to its forests. According to El País México, Pablo’s prosecution was orchestrated by local strongmen and businessmen in collaboration with the PRI government of Ulises Ruiz Ortiz. Pablo’s orchestrated disappearance was a precondition for unfettered logging.

Long before his arrest in 2010, Pablo’s work as a defender was marked by more minor skirmishes with the state. In 2000, he was convicted of “attacking public roads,” a charge later overturned on appeal. In the years that followed, he was accused, but not convicted, of assault, wood theft, and damage. The pattern is clear: Pablo repeatedly faced false charges in the state’s attempt to systematically wear him down.

Patterns of State Impunity

Pablo’s persecution is part of the national and continental pattern where indigenous land defenders are criminalised to secure access for corporate extraction. Criminalisation of indigenous dissent in Mexico and throughout Latin America is deeply connected to business operations. Instead of protecting the rights of communities, governments align themselves with powerful corporations, using the law to dismantle resistance, imprison leaders, and create the conditions for extraction.

“I don’t regret being a defender of nature. Everything I’ve been doing is for the good of the future of my children and grandchildren, of my community.”

— Pablo López Alavez

In Chiapas, Tlaxcala, and beyond, the tactic is tested, perfected, and repeated. Across the Americas, from the Mapuche in Chile to water protectors at Standing Rock, the logic is the same: target defenders, criminalise local communities, and break the resistance.

The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention has called for Pablo’s release, recognising that his imprisonment is punishment for defending land, water, and the rights of his people. Unless the violations identified by the UN are addressed, he will continue to, in the words of Front Line Defenders, serving an “informal life imprisonment.”

Life in Prison

Inside prison, Pablo’s days run on a strict cycle of repetition: dawn roll call, long hours in the carpentry shop, sparse meals of tortillas and coffee, and, when his family cannot visit with food, the added weight of hunger.

His family faces threats, break-ins, and illness in his absence, and his wife Yolanda bears the brunt when she dares to visit her spouse’s home. She has been threatened with death, forced to leave their mountain home, and now lives in the city for safety. “I’ve lost everything I built in my community. Now my family is living here in a rented house,” she said.

In various interviews over the years, Pablo has been repeatedly asked about his future and freedom, and the answers are always the same. The idea of abandoning the fight for the land does not cross his mind; his sense of duty leaves no room for personal indulgence.

Legal Timeline:

2000 – Convicted of “attacking public roads,” later overturned (Front Line Defenders).

2000s – Repeated accusations (assault, wood robbery, damages) without convictions.

2007 – Two men from San Miguel Aloápam killed; tensions escalate.

2010 – Abducted, beaten, held incommunicado, and handed to state police; accused of the 2007 killings.

2010–2017 – Detained without trial for seven years.

2017 – UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention declares his detention arbitrary, linking it to his environmental defence work.

2017 – Convicted and sentenced to 30 years.

2018 – Superior Court of Justice of Oaxaca confirms sentence, repeating errors from the first ruling.

2020 – State court orders retrial due to serious irregularities.

2021 – Court confirms order for formal imprisonment.

2025 – Re-sentenced to 30 years; ruling issued just hours after the hearing (El País México, Apr. 2024).