Everybody here has several birthdays. Intuition, telepathy, whatever, that’s the only way you survive this place

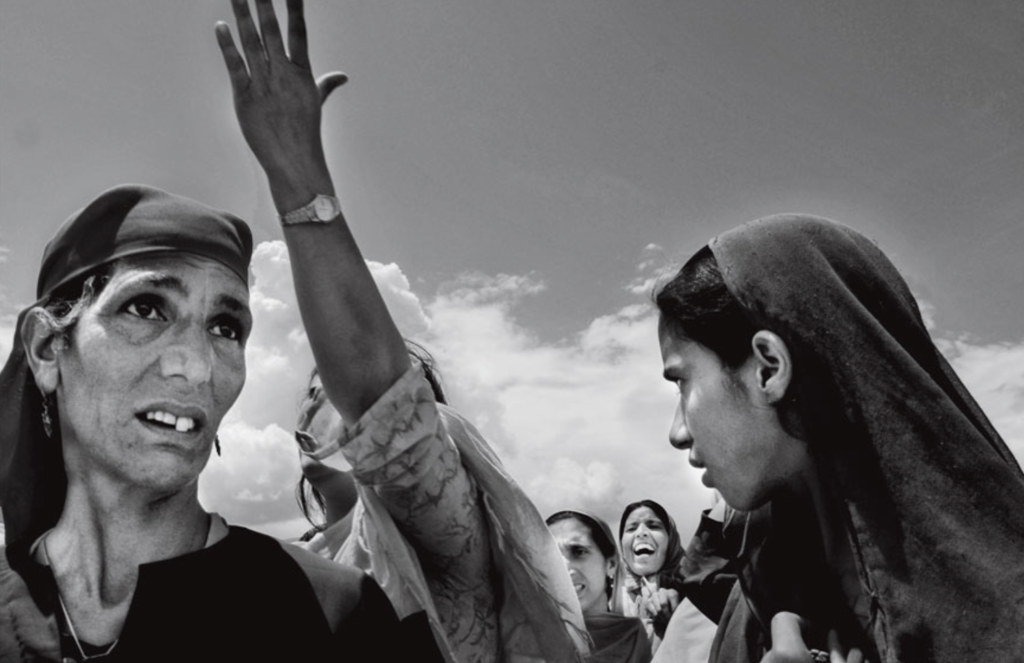

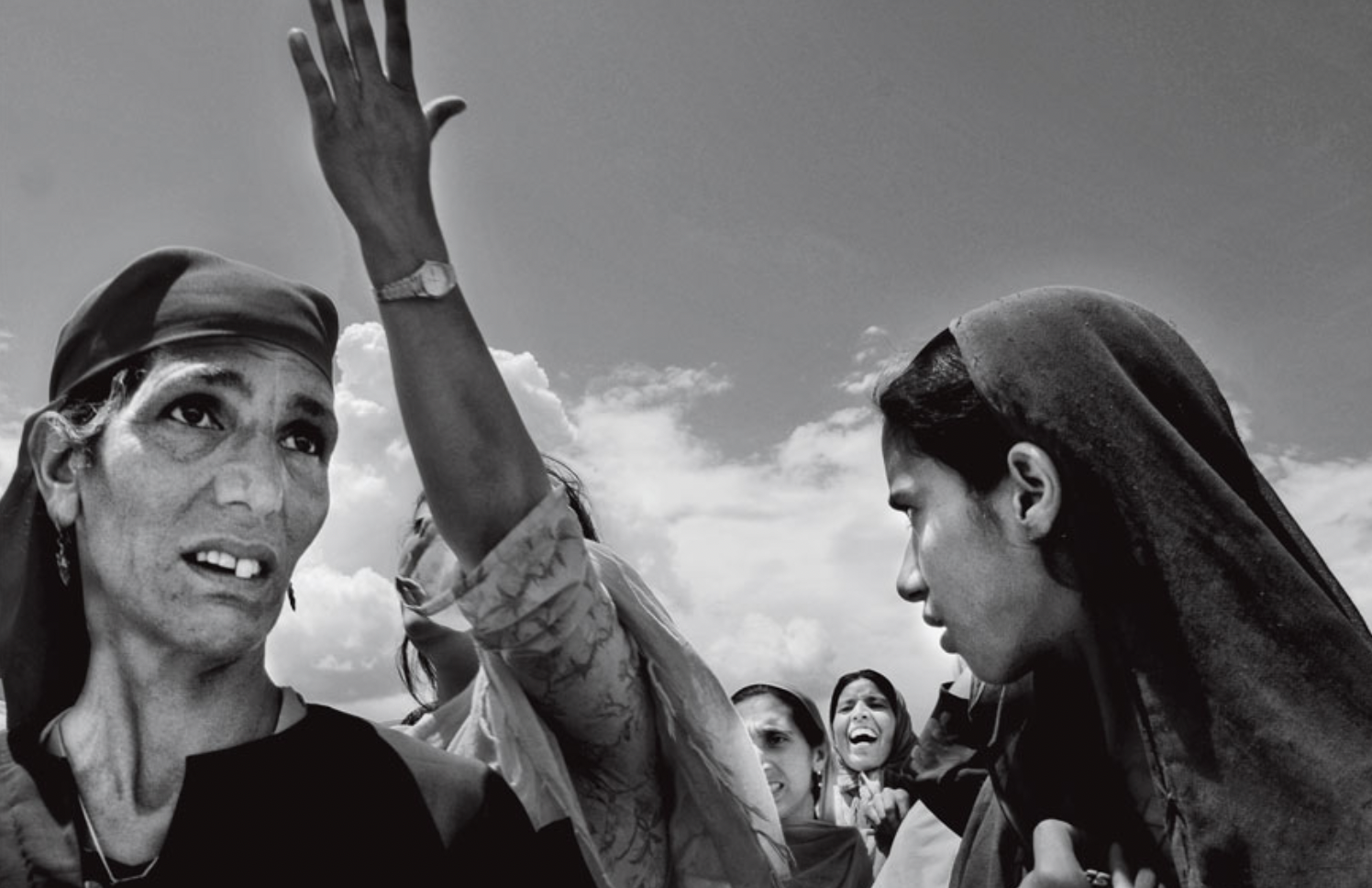

Two journalists in India-administered Kashmir were recently charged under anti-terror law. The police action wasn’t a first or the only one of its kind. Soon after, three others received the Pulitzer Prize for their photo-coverage of last year—this was a first. In our ongoing conversation on what it’s like for the news media on the ground, we bring you a photo essay based on our selections from Sanjay Kak’s Witness (2017). The stories and images below cover three decades of the conflict. Little has changed in the disputed region.

MERAJ UD DIN

When I was at Kashmir Times the teleprinter was on the same line as the phone. I don’t know why, but if you picked up that line, you could hear the wireless feed of the local Police Control Room. So whenever any one of us was in the teleprinter room, we would surely pick up the phone, hoping to catch something.

And one day I did: in December 1989, when Rubaiya Sayeed was kidnapped, that’s where I first heard it. To be honest, I didn’t think much of it until I casually told one of my colleagues. It’s only then that I realised what a scoop it was. The daughter of India’s Home Minister kidnapped by Kashmiri militants! A senior police officer later asked me where we got our tip-offs.

I said, “You’re the people who give them to us…”

By 1990, things had become bad and I had to move my family into the Press Colony. It was safer inside but we knew the Border Security Force hated all journalists. They used to say, “This is where news is cooked up.” Then in September 1995 the photographer Mushtaq Ali was killed by a parcel bomb, and it was not even meant for him. After that we all began to be very careful, and for the first time we felt real fear. It was the beginning of a terrible time.

I began to carry two identity cards in two different pockets, one in my shirt, and another in my pants. In case something happened, I wanted people to know who they had found. Every day was full of such sights… At one grenade blast I saw an elderly man rushing around helping to pick up victims, tirelessly. Until he turned over this one body, and realised it was his own son. All of us photographers wept that day. — Srinagar / March 2016

JAVEED SHAH

I was walking just two steps behind a soldier of the Rashtriya Rifles once, on an assignment at Haigam. Suddenly the soldier jerked, and dropped to the ground. He had taken a bullet in the middle of his forehead. What saved him was his protective headgear, the patka that they wear. What saved me, I guess, was him.

Like everybody else here, I have several birthdays. Call it intuition, telepathy, whatever, but I do believe in it, because that’s the only way you can survive this place.

There was this encounter at the Tibetan Colony near Eidgah in Srinagar. Some buildings were on fire and I had taken shelter behind the bam gaed, the fireman’s truck. Right next to me was a soldier from the Border Security Force, firing at the militants from so close that the empty shells were dropping at my feet.

When there was a pause I decided to get up and move position. Exactly at the moment I stood up, a BSF soldier walked across my path, so sudden that I didn’t even notice him come. He took a bullet, and was shot dead. And fell right there, right in front of me.

Fifteen minutes later, I was still shaking. The firing had started all over again, and when it finally stopped, from somewhere far in the Eidgah grounds, I heard a soldier shout: “Sir, usko uda doon?” (Sir, shall I knock him off?) I didn’t even realise he was talking about me until I heard his officer’s response—“Nahin beta, ho gaya ab…” (No son, it’s over now…).

Why did I start shooting so many of those distorted reflections those days? Maybe it was to mirror the madness that had taken over our streets. An experiment of sorts. Or a sign of my frustration at what was going on. Who can say. — Srinagar / March 2016

DAR YASIN

When you are covering a funeral, it makes a difference who the person killed is. If he is a militant, there is public anger, but it is still controlled, within limits. Because once he becomes a militant, his family already begins to think of him as a martyr.

I’ve heard a martyred militant’s mother telling mourners to stop wailing, saying, “My son has gone to Paradise, why cry for him?” I’ve seen the mothers of martyrs come to a funeral so that they can whisper messages in the ears of the dead. It’s their way of sending word to their sons in Paradise, where all the boys will certainly meet.

It’s when a civilian is killed that things can get really out of control. It gets crazy. The families tend to lose it, sometimes they even attack the photographers. Then you have to bear it, take a few hits…

We have to be where the news is happening that day. Even if nothing is happening I still need to be sitting around at my office all day, just in case there is breaking news. Most of the time there is a routine to the work. You can see it in the keywords that accompany my pictures—Protest, Killing, Funeral; Gun-battle, Grieves, Searches. Only sometimes something happens that shakes you up.

I was shooting once near the HMT Factory, on the outskirts of Srinagar. It was a daylong encounter with militants, and the Army was keeping us far from the gun-battle. When it was over, and all of us photographers rushed in, I got busy, looking at the bodies, taking pictures—the usual.

Suddenly I had the feeling that the place looked oddly familiar, and stopped. When I looked around I realised that the place I was standing in was the burnt-out shell of my old school. I was so shaken; I must have stood there for several minutes, my ears ringing, unable to move. — Srinagar / October 2016

JAVED DAR

I can remember the day the first crackdown happened in our village.

I had just finished my Matric exam: it was June 9, 1992. The Army arrived early in the morning, and they came in trucks, so we knew this was not going to be routine.

We were meant to start planting paddy that day, and had left the house early. The first day of planting is a sort of festival in Kashmir. We were stopped by the soldiers as we walked to the far end of the village, and told to go back home. My father tried to argue but they said no: “Boys like him are the terrorists.”

In the village, everyone had been gathered in an open space near the stream. They had already pulled out three or four boys from the crowd—I don’t know what process they used to decide who to pick and who to leave out. Perhaps because I was tall, and had a bit of a beard, they thought I qualified.

A house nearby had been emptied out, and everyone in that home, men and women, had been herded out. Then those of us who were picked out were put into different rooms. In the one near mine I could see my tutor, Gulzar sahib.

Soon I could also hear his screams. For almost half an hour I sat there with those sounds pouring over me. I was cold, shivering like a leaf, as if it was chilai-kalan in the month of June, fearful of when they would come to take me too.

When they brought Gulzar sahib back to the room I was in, he was completely naked. We both averted our eyes out of respect. Then they came in and stripped me too. I begged them not to, with folded hands, but it had no effect. They took me to a nearby bathroom, which was new, and not tiled yet, with a floor of rough cement. The soldiers tied my hands behind me, passed a stick below my knees, and then knocked me over. After that they stuffed a tightly rolled up cloth in my mouth—I remember it had a camouflage print. Then they covered my head with another cloth, and began to pour water over it.

Each time they poured there came a point where I felt that I was about to die. Then they’d let me go. Then again. And again. There were only two questions: “Where are the militants?” “Where are the weapons?”

Eventually the soldiers gathered us together and began moving us out of the building. Just then a group of women from the village came and surrounded the truck into which the soldiers were taking us. They literally pulled us out of it. They took us out of the hands of the military! It was nothing less than a miracle.

For months after I had to sleep in my father’s room, in his bed. And my dreams were all nightmares. Was I thinking about photography then? No, nothing. The only dream, the only ambition, was to stay alive and secure. — Srinagar / April 2016

ALTAF QADRI

I’ve seen photographers who came to Kashmir from outside making great work here. But even if this sounds a bit contradictory, I believe there is always an issue with those on assignment, because they are here only for a brief period.

In my case the story has no limits. I belong to it.

Amongst journalists here too there is always a section that is not reporting straight, and putting a spin on the news from Kashmir. And of course the entire Press experiences the backlash. There have been situations when there has been a lot of hostility, especially against Delhi-based TV channels, who often end up showing something very biased and unconnected to the reality here.

A man had been blown up while defusing an Improvised Explosive Device in Palhalan village. At least that’s what the newspapers in Srinagar had reported. Later that morning, when we photographers got there, the people of the village were so angry they were ready to lynch us. We ended up being chased through the village for almost 300 metres before a conversation could even be started. “You only carry the Army version,” the furious young men said to us. “Whatever they say matters. What we say never gets reported.”

“Would it be better if we didn’t come to report?” I asked one of them, “then you would be more angry, and accuse us of keeping away!” It usually takes a lot of persuasion by the buzurg (village elders) to restore the balance. Still I always like to talk, and never give up without arguing for what I believe in.

Whether I end up getting slapped up or beaten, no issue, that’s part of it. — Srinagar / October 2015

SUMIT DAYAL

I went back to Srinagar in 2009 after almost 17 years.

I don’t know if it felt like home but it certainly felt like it had shrunk. When I was a boy my Nani would treat the stretch between her home in Durganag and Jan Bakers like it was a border crossing, sarhad paar, you know. It turned out to be right next-door.

How much everything else had changed. There was a marsh near my father’s house in Iqbal Colony; it used to feel like a lake. Now there are no more reeds or water, it has become a road, with only housing and construction. And the tangewala, who always gave me a ride on his horse-cart on his way home, he’s changed too. He has become a property dealer.

I guess I was still trying to see the city as I remembered it. I was not sure if all the change was good or bad, just that everything had changed. If I was trying to recall something of the happiness that an 8-year-old had experienced in Kashmir, that was not going to happen. There was not going to be any going home to Kashmir.

Even after that first trip I kept returning, without any real agenda, just to loiter around. It was a wonderful time; I could concentrate on the photography. How does the medium affect what we do? Things I had seen and learnt over the years could now be deployed.

The problem was that it soon became difficult to make sense of what I was bringing back. Amongst the pictures there was the street stuff, and there was the loitering around. There was a straightforward political story, and a personal one. How were they to be put together? That was the real problem. — Srinagar / January 2017

SHOWKAT NANDA

The cement bridge in Baramulla town has come to be called ‘The Bridge of Battle’. Some say that the angel of death lives there, since it has consumed so many young lives, mostly during violent clashes between protesters and paramilitary soldiers.

One day I witnessed this for myself, as a child of barely 12 years lay in my arms, his life slipping away, one breath at a time.

It was a rainy afternoon and routine clashes were taking place between protesters and paramilitary forces. I sat some 100 metres away from the bridge, looking through photographs on my camera’s LCD. Suddenly I heard a rumble of gunfire followed by loud shouts. I saw three or four youths coming towards me, carrying an injured boy, his blood leaving a trail on the ground behind them. I ran to them and took the blood-drenched, half-dead child in my lap, pleading with the people around us to call for an ambulance.

A dozen desperate young boys formed a ring around us, each suggesting ways of saving his life. But I knew he was not going to make it. The bullet that had pierced the left side of his chest had left a gaping wound. He lay there in my arms, blood oozing from the mouth. I tried to smile as I told him he was going to be all right. He smiled back. Perhaps in disappointment, as if he knew I was lying.

As I looked up at the sky to hold back my tears, I felt a freezing numbness in his body. His smile had turned into a ghastly stare. He was dead. Hundreds had already gathered, shouting Shaheed ki jo mout hai, Woh qaum ki hayat hai (The death of a martyr is life for a nation). I did not know him or his name. But before he was taken away, he was able to rest in peace in my arms for a moment. This must be the peace India keeps talking about, I thought.

I wanted to scream. I wanted to throw stones. Not one, not two, but millions of them. But, apart from clenching my teeth, I could do nothing. With the burden of journalism hanging around my neck, I felt powerless. It was dangerous for a journalist to take sides, I had been told.

The battleground was deserted by now; no one dared face the soldiers in case they should open fire again. Then just a few minutes later a small child appeared, as if from nowhere. He ran towards the paramilitary soldiers, throwing stones at their armoured vehicles, seemingly without fear of being chased, beaten, arrested or shot. I overheard somebody say that the stone-throwing boy was a schoolmate of the child who had just died in my arms.

In those few moments I simultaneously witnessed the death of innocence and the birth of defiance. — Baramulla / August 2016

SYED SHAHRIYAR

Pictures too play a role in surveillance. When they bring the boys into the Nowhatta police station, there are photographs up on the wall. The faces that are circled are what the police call ‘nominated’ stone-pelters. Often they play back a video of the stone-throwing to them, saying we know what you do.

Someone once shot a video of a local boy snatching a gun from a policeman during a protest. That was in 2010, the year that Tufail Mattoo was killed. When the video was aired on the local channels, the police were quickly able to locate the boy, and arrest him. At Tufail’s funeral the next day many of the photographers were thrashed. People called them mukhbir (informer).

Till a few years ago we tried to position ourselves on the side of the protestors. It gave us a very different perspective on their battles with the paramilitary. But that changed completely after 2013. It’s become too dangerous for the photographers. Pellet guns are everything for the police now—I don’t understand it, they seem to love these pellet guns, it’s like a narcotic for them. Sometimes at a protest they shoot people in the leg, even when the stone throwing is not too heavy, just so that they can identify them later. A sort of tag.

My friend Abid was playing volleyball near his home in the evening once, when he was called in to the police station. Abid told them that he hadn’t been at any protests. But the cops insisted, and made him roll up the legs of his track pants. And there they were, the pellet marks on his calves. — Srinagar / May 2016

AZAAN SHAH

Every photograph is a self-portrait, I’ve read.

Maybe that’s why I don’t find myself in pictures of busy, crowded places, but in quieter, more isolated spots. Those give me the most satisfaction. And I like to shoot individuals, just one figure against a background, a reflection of their loneliness.

I’m never in a hurry to take pictures, but just happy to understand what is going on.

I would love to shoot in Old Delhi, for example, or Varanasi. But it takes time to get familiar with the flow of a place. You need to understand how a city unfolds.

You have to accept what is around you, and then try and make pictures. That’s what I try to do. (But you have to start in the morning because things get messy in the day…)

Would I like to be invisible? Well, I’ve been taking a lot of pictures on my smartphone recently. It’s made me realise the beauty of imperfection in photography. Sharpness is overrated, and I don’t like photos that are too sharp, or too perfect in terms of ‘dynamic range’. Nor do I like photos that are cropped perfectly.

Real life and the streets are not perfect. It’s the imperfect edges of a photograph that gives it ‘realness’. — Srinagar / October 2016