The bumpy road of reservations: The 7 August 1990 announcement on the Mandal Commission’s recommendations by V.P. Singh

This essay is part of a series by Prof. V. Krishna Ananth where he recalls the events that determined the course of politics in post-colonial India, sometimes reinforcing the “idea of India” and otherwise distorting that. The essays revolve around specific events and their consequences and the facts are placed in context and perspective to comprehend the times in which they are being recalled and re-presented. The series recalls the events on their anniversary, they do not follow a chronological order and are seen as moments in history.

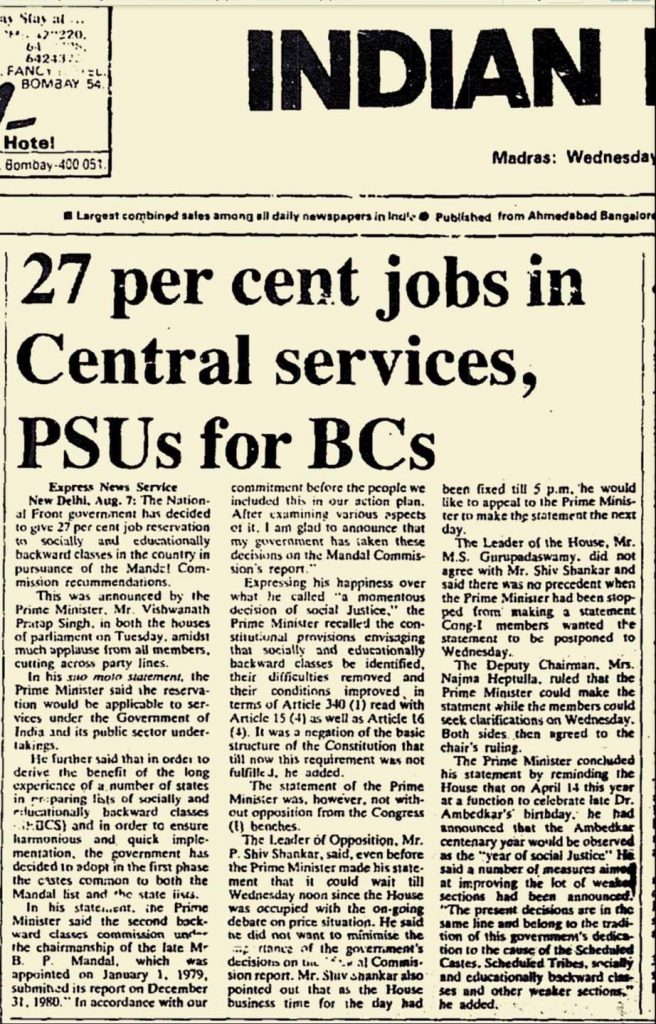

On 7 August 1990, Prime Minister Vishwanath Pratap Singh (V.P. Singh) informed the Lok Sabha of the decision to implement part of the Report of the Second Backward Classes Commission (Mandal Commission). The Report’s recommendations involved the reservations in central government jobs to Socially and Educationally Backward Classes (SEBCs).

The announcement did not cause any stir and there was no sign of the violence it would provoke in north Indian towns and cities in the following weeks. There was also no sign of the tectonic shift it would bring in political discourse and electoral politics as all eyes were on the internecine battle within the Janata Dal and the uncertain future of the National Front Government that Singh headed.

A couple of days later, on 9 August 1990, Singh made the same announcement in the Rajya Sabha saying: “[T]his is the realization of the dream of Bharat Ratna Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, of the great Periyar Ramasamy and Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia.” In hindsight, it is clear that Singh knew the fate his government would meet and was preparing to let go of his ministry. He was, however, committed to alter the discourse in a decisive manner and it took a while for critics of reservations to read the short statement between the lines.

The National Front Government with V.P. Singh as Prime Minister was straining to keep itself going less than a year after swearing in on 2 December 1989 as it relied on both Left parties and the external support of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Singh himself captured this reality; seeking the vote of confidence for his government on 7 December 1989, he acknowledged: “With a heterogeneous socio-economic system, the political system cannot be homogeneous.”

Prime Minister V.P. Singh and part of his cabinet cut their teeth in the Socialist Party in the 1960s and were perceptive to the imperative for the Janata Dal to re-invent its base. The social alliance with Ahir-Jat-Gujjar-And-Rajput (AJGAR) that helped win the elections in November 1989 was unstable and the Mandal Commission Report would be of help.

Even though the announcement on 7 August 1990 was triggered by expediency, V.P. Singh’s intents were clear. His intervention during a debate in the Lok Sabha on 25 September 1991 put the issue on Mandal in perspective:

[If] you take the strength of the whole of the Government employees as a proportion of the population, it will be 1% or 1-1/2 [. ..] We are under no illusion that this 1% of the population, or a fraction of it will resolve the economic problems of the whole section of 52%. No. We consciously want to give them a position in the decision-making of the country, a share in the power structure. We talk about merit. […] That the section which has 52% of the population gets 12.55% in Government employment. […] I want to challenge first the merit of the system itself before we come and question on the merit, whether on merit to reject this individual or that. And we want to change the structure basically, consciously, with open eyes.

This was not an after-thought. The Office Memorandum issued by the National Front Government on 13 August 1990, a week after the Lok Sabha announcement, stated: “In a multiple undulating society like ours, early achievement of the objective of social justice as enshrined in the Constitution is a must. The Mandal Commission was established by the then Government with this purpose in view, which submitted its report to the Government of India on 31.12.1980.”

The struggle for justice for SEBCs is as old as the Constitution and the scheme of reservation in government jobs was an integral part of this quest. However, the leadership of the Congress Party found it expedient to push this constitutional mandate under the carpet. Jawaharlal Nehru quickly enacted the Constitution (First Amendment) Act, 1951 meant to ensure constitutional protection to reservation for the Scheduled Castes (SC) in educational institutions. The cabinet under his command, however, did not show a similar enthusiasm. Nehru constituted the First Backward Classes Commission with Kaka Kalelkar as chairman on 29 January 1953 just a few months after he was first elected as Prime Minister (15 April 1952.) The Commission was constituted under Article 340 of the Constitution. Clause (1) of the Article reads:

The President may by order appoint a Commission consisting of such persons as he thinks fit to investigate the conditions of socially and educationally backward classes within the territory of India and the difficulties under which they labour and to make recommendations as to the steps that should be taken by the Union or any State to remove such difficulties and to improve their condition […]. (Emphasis added)

The Government had an option not to constitute such a commission, but Nehru did not exercise this option. This was evidence of his own commitment to the cause as much as a response to the Constituent Assembly’s demands to treat Other Backward Classes (OBCs) in the same way as SC. Article 16 (4) of the Constitution met this demand halfway as it enabled the State to make “any provision for the reservation of appointments or posts in favor of any backward class of citizens which, in the opinion of the State, is not adequately represented in the services under the State.”

A list of the “backward classes of citizens” was necessary to give effect to Article 16(4) and Article 340 was the provision that set out the procedure to identify such socially and educationally backward classes. The use of words was distinctly different from the provisions regarding the untouchables that the Constitution addressed as Scheduled Castes (following the colonial census).

The Kaka Kalelkar Commission Report submitted on 30 March 1955 was based on extensive field research done across the country. From the onset, the Commission found relevant to consider the backwardness of classes; their traditional occupations and professions; their literacy rate or the general educational advancement; the estimated population; their territorial distribution and concentration in certain areas. The Commission also held that the social position a community occupies in the caste hierarchy would have to be considered along with its representation in government service or in the industrial sphere.

According to the Commission, traditional apathy for education because of social and environmental challenges, occupational handicaps, poverty and lack of educational institutions in rural areas were among the causes of educational backwardness. The Commission put out a list of 2,399 backward castes or communities, 837 of which were categorized as most backward. The Commission also recommended wide ranging measures such as agrarian reforms, reservation in jobs and special measures to ensure their access to education.

However, Kaka Kalelkar, after signing the recommendations, developed doubts on the Report and sought that it should be rejected on the ground that reservations and other remedies based on caste would not be in the interest of society and the country. The principle of caste, in his opinion, should be eschewed altogether.

The Government was certainly not bound by such ideas – especially after a report based on meticulous research and methodological rigor – but Nehru and his cabinet preferred to hold on to them and put the Report and its recommendations to sleep. The Action Taken Report (ATR) released on 3 September 1956 held that – while the caste system remained the greatest hindrance in the path towards building an egalitarian society – the recognition of a caste as backward even to ameliorate their conditions may serve to maintain and perpetuate caste-based distinctions. For this reason, the Government decided to reject the Commission’s recommendations and declared the need for a more robust mechanism to identify the backward classes.

After a long while, on 14 August 1961, the Union Government wrote to the States granting them liberty “to choose their own criteria for defining backwardness: and use these to make out lists of classes to whom they may extend reservation in jobs under the State Governments as well as reservation in educational institutions.” The letter said that “in the view of the Government of India, it would be betterto apply economic tests than to go by caste” (Emphasis added) and that “even if the central government were to specify under Article 338(3) certain groups of people as belonging to ‘other backward classes’ it will still be open to every State Government to draw up its own lists.”

Reservations for central government jobs and central educational institutions were restricted to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (ST). After the letter, various State Governments went about setting up commissions and effecting reservations in jobs and educational institutions. There are two important facts about these initiatives: most of them were set up in states outside the Gangetic valley and the Mungeri Lal Commission in Bihar was set up when Socialist Party’s Karpoori Thakur was Chief Minister. Similarly, in Uttar Pradesh, the Cheddi Lal Sathi Commission was appointed when H.N. Bahuguna was Chief Minister. The point is that the Congress Party, in Nehru’s time and after, did not take the spirit of Article 340 seriously.

The appointment of the Mandal Commission has to be seen in this context. The Janata Party, born on 30 January 1977, promised the appointment of a Second Backward Classes Commission in its manifesto. The Janata Government, however, did not show much enthusiasm in this regard. It was only on 1 January 1979 that the Union Government notified the Second Backward Classes Commission. In spite of the delay in the appointment, the Janata Government’s choice of the Commission’s chairman was significant. Mandal was a member of the Lok Sabha, a socialist of standing and had been the Chief Minister of Bihar in 1968. Unlike Kaka Kalelkar, Mandal was among the socialists who had clear that the roots of backwardness in the Indian society lay in caste-based exclusion. Mandal was not bleary eyed in his approach to end social and educational backwardness and in his understanding of the constitutional provisions contained in Articles 15(4) and 340.

This was clearly stated in a report submitted on 31 December 1980. Referring to Kaka Kalelkar’s Report, the Government’s ATR and the 1961 communique to the State Governments, the report said:

As the main thrust of the Government’s development programmes has always been the removal of mass poverty, this pre-occupation with economic criteria in determining backwardness is quite understandable. But however laudable the objective may be, it is not in consonance with the spirit of Article 340 of the Constitution under which the Commission was set up. Both Articles 15(4) and 340(1) make a pointed reference to “socially and educationally backward classes.” Any reference to “economic backwardness” has been advisedly left out of these Articles. […] It may be possible to make out a very plausible case for not accepting caste as a criteria [sic] for defining “social and educational backwardness.” But the substitution of caste by economic tests will amount to ignoring the genesis of social backwardness in the Indian society. (Emphasis added)

Mandal and the Commission were not groping in the dark. The higher judiciary over the years intervened in regard to the State Governments’ exercises since 1961. Various High Courts and the Supreme Court had by this time settled the scope of Articles 15(4) and 340 stating that caste is a class of citizens; that reservation in jobs shall not exceed 50 per cent of the total (and this including reservations already in existence to the SCs and STs); and that objective criteria should be developed for identifying OBCs. These criteria were settled in the course of two cases involving reservation for OBCs in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu: Balaji vs State of Mysore (1963) and P. Rajendran vs State of Tamil Nadu (1968).

With the benefit of hindsight and his own conviction that “social backwardness was the direct consequence of caste status,” the Mandal Commission went about identifying the SEBCs using systematic survey methods and according index points to communities thus identified. The Mandal Commission’s methodology involved eleven indicators to determine social and educational backwardness. These indicators were grouped under three distinct headings – social, educational and economic.

The social indicators were: castes and classes considered socially backwards by others; castes and classes that depended on manual labor for livelihood; castes and classes where 25 per cent of females and 10 per cent of males get married at an age below 17 years in rural areas and ten per cent females and five per cent males do so in urban areas; castes and classes where participation of women in work is at least 25 per cent above the State average. The educational indicators were: castes and classes where the number of children aged 5-15 years who never attended school is 25 per cent above the State average; castes and classes where the rate of student drop- out in the same age group is 25 per cent above the State average; castes and classes where matriculation is at least 25 per cent the State average. The economic indicators were: castes and classes where the average value of family assets is at least 25 per cent below the State average; castes and classes where the number of families living in kucchahouses is at least 25 per cent above the State average; castes and classes where the source of drinking water is beyond half a kilometer away; castes and classes where the number of households having taken a loan is 25 per cent above the State average.

The Mandal Commission accorded separate weight points to indicators in each group (three for social indicators and two for each educational and economic indicators) stating that economic indicators, along with social and educational ones, were important as they directly flowed from social and educational backwardness thus highlighting that socially and educationally backward classes are economically backward as well. Following this system, communities and castes whose score crossed 11 out of the 22 points were declared as Socially and Educationally Backward Classes of Citizens as warranted in Article 340 of the Constitution. These communities and castes constituted 52 per cent of the population (according to the 1931 Census, when castes were listed for the last time) and had 27 per cent of central government jobs reserved to them. Besides developing criteria to identify SEBCs, the Mandal Commission also followed the Supreme Court’s decision that reservations shall not exceed 50 per cent.

Even though the Mandal Commission’s report aimed at realizing the spirit of Articles 15(4) and 340 and was redacted after a meticulous reading of earlier judicial pronouncements, Indira Gandhi’s government – in power since January 1980 – refused to follow it. The Report was tabled and debated in Parliament in 1982. The Home Minister R. Venkataraman informed that Parliament that the Government was looking for consensus on some aspects of the report and that there were consultations between ministries and with State Governments on some points. The Mandal Report came up for discussion in Parliament again in 1983 when P.C. Sethi was the Union Home Minister. He said: “I would like to remind the House that although this Commission had been appointed by our predecessor Government, we now desire to continue with this Commission and implement its recommendations.”

Successive Congress Party Governments between 1980 and 1990 made no effort to follow the Report until V.P. Singh’s Government issued an Office Memorandum implementing parts of the Mandal Commission’s recommendations.

While the announcement by V.P. Singh on 7 August 1990 in the Lok Sabha was uneventful, things began to change a couple of days later. While protests took place in various towns in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Haryana, political parties across the spectrum shied away from openly opposing reservations. OBCs in fact constituted more than half of the population and alienating them would amount to bad politics. The parties’ ranks and files, however, sided with the protestors. Things changed after 19 September 1990, when Rajiv Goswami, a college student in Delhi, set himself on fire in protest against V.P. Singh, his Government and the Mandal recommendations. In quick succession, there were other suicide attempts in Delhi, Hissar, Sirsa, Ambala, Meerut, Lucknow and other towns across the Gangetic valley.

Meanwhile, the constitutional validity of the 13 August 1990 Office Memorandum was challenged through a writ petition in the Supreme Court. A Constitution Bench consisting five judges, even while admitting the petition on 11 September 1990, refused to stay the Office Memorandum. However, a month later they stayed the operation and posted the matter to be heard by a nine-member Bench. The dispute (Indra Sawhney and Others v/s Union of India) was brought to an end on 16 November 1992, when the Supreme Court, in a 6:3 judgment, held the 13 August 1990 order constitutionally valid.

The judgment put a stamp of approval on a host of earlier deliberations stating that caste as a category shall be used to determine the SEBCs as laid out in Article 340 of the Constitution. The nine-member bench upheld the verdict in the M.R. Balaji vs. State of Mysore (1963) that caste is a valid category to determine Social and Educational Backwardness and that job reservations shall not exceed 50 per cent of total posts. The leading judgment was authored by Justice B.P. Jeevan Reddy with whom Chief Justice M.H. Kania and Justices M.N. Venkatachalaiah, A.M. Ahmadi, S.R. Pandian and P.B. Sawant concurred. The dissenting minority was constituted by Justices T.K. Thommen, Kuldip Singh and R.M. Sahai.

The majority among the six judges who upheld the reservation also added that the elite among the Other Backward Castes have to be excluded from the scheme. The Congress now in power issued a Government Order on 8 September 1993, setting out the criteria for identifying the elite and ensure the implementation of 27 per cent reservation in central government and public sector jobs for Other Backward Classes.

The relevance of Mandal, however, was not restricted to a few thousand central government jobs. Its impact on the political discourse, made Mandal and the 7 August 1990 announcement by V.P. Singh a historical moment. Their immediate impact was a social and political alliance between OBCs and Dalits in the Gangetic valley. This allegiance, even if for a short while, brought an end to the Congress Party’s prospects to power in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

Another repercussion of Mandal and the 7 August 1990 announcement was the BJP ’s response. In a conclave in Delhi on 12 September 1990, they made plans for a rath yatra. The BJP National Executive meet in Bhopal (14-16 September 1990) to define the date and the route: the yatra was to begin in Somnath, Gujarat, on 25 September 1990 and reach Ayodhya on 30 October 1990, traversing 10,000 kilometers through ten states and 200 Lok Sabha constituencies.

The anti-Mandal agitation had gathered mass by this time. BJP President L.K. Advani had a taste of the intense students’ hatred for V.P. Singh and knew that the BJP, on whose support the Government survived, was held equally responsible for the Mandal decision. For this, when he went to visit Goswami, he was attacked by the agitators and prevented from entering the premises. Afterwards, Advani did not hesitate to attack the 7 August 1990 decision wherever he stopped in the course of his rath yatra. His speeches were a blend of aggressive Hindutva and anti-Mandal rhetoric: upper caste youth across north Indian states were offered a political alternative they could look up to. The association of the symbol of Ram and Ayodhya helped the BJP forge a Hindu identity that was not restricted to upper castes, but could include Other Backward Castes, Dalits and Adivasis.

The Mandal Commission’s recommendations were not restricted to reservation in central government jobs as V.P. Singh’s announcement on 7 August 1990 addressed only a part of it. The Mandal Commission Report dispelled any illusion that reservation in jobs would end the socio-economic inequalities. The Commission, however, was clear that this was “an essential part of the battle against social backwardness,” but recommended several other measures including financial assistance. The Report went on to stress that these “will remain mere palliatives unless the problem of backwardness is tackled at its root” pointing to the fact that the majority of small land-holders, tenants, agricultural laborers, impoverished village artisans, unskilled workers belonged to Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Other Backward Classes.

Radical land reforms, the Commission stressed, will help transform the society:

It is the Commission’s firm conviction that a radical transformation of the existing production relations is the most important single step that can be taken for the welfare and upliftment of all backward classes. […] The Commission, therefore, strongly recommends that all the State Governments should be directed to enact and implement progressive land legislation so as to effect basic structural changes in the existing production relations in the countryside.

This, however, was a cry in the wilderness. By the time the Mandal Commission’s recommendations were taken up in August 1990 and Supreme Court resolved their constitutional validity in November 1992, political priorities in India had changed. The liberal economic policy shift since July 1991 rendered all thoughts of radical transformation of the agrarian structure a thing of the past. Consequently, the opportunities that Mandal offered to realize the constitutional scheme of social, economic and political justice were left to fossilize.