Can a secular state grant citizenship selectively based on religion? The most ominous implication of the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 (CAA) emerges when it is read along with the possibility of an India-wide National Register of Citizens (NRC). Muslims are a 200-million strong minority in India. A failure to prove citizenship on account of loss of documents or a lack of them will mean a loss of citizenship for this minority. We must remember that India is a woefully undocumented country. The poor, the landless, and those on the margins, have neither the resources to procure documents nor a sympathetic State to hold their hand. The specter of statelessness looms on the horizon for a large section of the population. In the current political climate such undocumented people will also have to face the ire of public opinion which has been systematically poisoned by the BJP through persistent use of terms like “termites” and “infiltrators”. The Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 and the National Register of Citizens are twin weapons of whipping up communal frenzy, reducing Muslims to prospective second-class citizens in their own country. The BJP understands the explosive potential of these legislative and administrative tools and it will leave no stone unturned to milk them for all their worth. The Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 is parochial and it is not based on “intelligible differentia” which is a necessary requirement for all classification under Article 14 (Right to Equality) to stand the test of judicial scrutiny.

1

At the stroke of the midnight hour when the world slept, India rudely awoke to pestilence and bigotry. A moment comes, which comes but rarely in history, when we step out from the good into the bad, when an age ends, and when the soul of a nation is gouged out from its bone and flesh, when its spirit is finally smothered. I apologize for mutilating this radiant phrase, borrowed from Jawaharlal Nehru, to sound the death-knell of our Republic as it once stood in the moment of its creation and as we have known it in the last 70 years. The Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 (CAA) is what has caused this tilt away from our constitutional and civilizational moorings.

Isn’t it a cruel quirk of fate that the Lok Sabha declared the passage of the Citizenship Amendment Bill at 12:02 am—literally at the stroke of the midnight hour? One is naturally drawn into making an odious comparison with another such momentous event in the life of India that occurred famously when the clock struck midnight on 15 August 1947—the very moment of India’s birth as a nation. Nehru—whom Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bhartiya Janta Party (BJP) abhors—used his celebrated “tryst with destiny” speech[1] to mark India’s independence in the Central Hall of Parliament in what came to be regarded as a historic and inspiring moment when we, as Indians, awoke into a life of freedom. Despite the raging fires of communalism that led to Partition, the Constituent Assembly had the sagacity to reject the two-nation theory and lay the foundations of an India that was inclusive, democratic and plural.

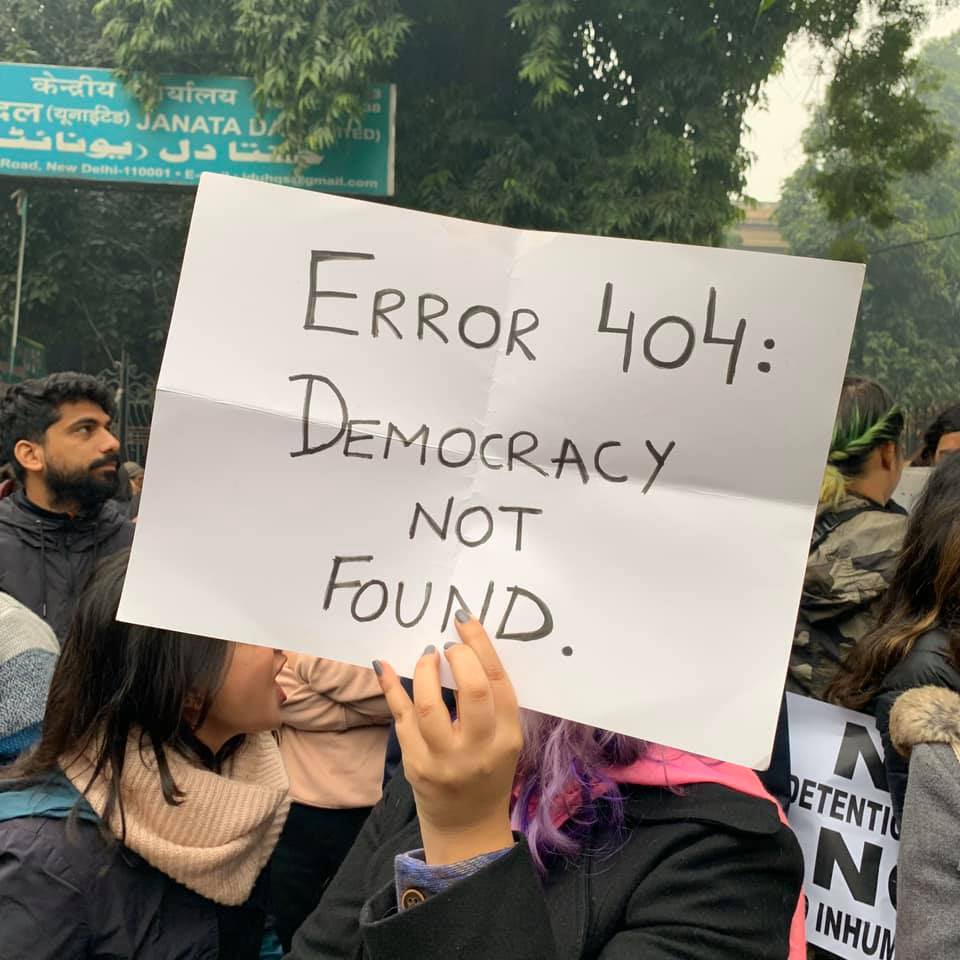

For the last fortnight India has witnessed unprecedented protests, sometimes violent, both in the Northeast where cultural identity is much stronger than the affinities of religion and in other parts of India, especially university campuses, that have risen in unison to oppose this manifestly sectarian law.

What followed is an ugly tale of police repression with the police forcibly entering libraries and hostels and using disproportionate force on students—especially in universities like Jamia Millia Islamia and Aligarh Muslim University, leaving the administration open to the charge of willfully committing atrocities against Muslims as though to teach them a lesson for opposing the citizenship law.

Since then, the fires of dissent have spread enveloping many states where people have poured in hundreds of thousands on the streets to register their disapproval against a law that threatens to divide the country along religious lines. The footage of eminent historian Ram Chandra Guha being forcefully whisked away by the police from a protest site in Bangalore is emblematic of how this government has responded to the voice of the people. It has shown to the world that it has no patience for contrarian views, no appetite for being questioned and certainly no stomach for dissent.

Thousands have been arrested or detained across India since protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 began in early December with the introduction of the Bill in the Lok Sabha. A glaring aspect of the government response has been the shutting down of internet services to cripple communication and thwart the effective organization of these protests. In what is a mind-boggling statistic, India has the dubious distinction of being the country with maximum number of internet shutdowns in the world in recent years, and especially in 2019. It is a matter of great concern that a democracy like India can block people’s access to information with such impunity. The more a government resorts to draconian measures like blocking communication or shutting down public transport on the ambiguous pretext of maintaining law and order, the more it acquires the characteristics of a police state and the thinner becomes its threshold for appreciating the voices of dissent.

The protests have been most vociferous in the north Indian state of Uttar Pradesh and so has been the police crackdown. Egged on by the Chief Minister, Yogi Adityanath, who has made public statements calling for revenge and the seizure of property of protestors – mostly Muslims – Yogi’s police force has been most brutal on Muslims, raising concerns of communal targeting in many quarters. According to numerous media reports, mostly young Muslim boys have been killed in Uttar Pradesh so far. The most heart-wrenching stories include the death of Suleiman, a young student, an aspirant for India’s civil services, barely 20 years old, who succumbed to gunshot injuries. His family members have alleged that Suleiman had nothing to do with the protests, he was picked up by the police when he was returning from the mosque after offering namaz and shot in cold blood.

There have been disturbing reports of policemen entering houses of people in Muslim localities, especially in Muzaffarnagar, intimidating residents and in some cases mercilessly thrashing them. The government has also sealed 67 shops of Muslims in Muzaffarnagar alleging that protestors took refuge there. Another poignant story is that of a school teacher, Sadaf Jafar, who was beaten by male police officials after being arrested in Lucknow. Or the story of Saghir Ahmad, an 11-year-old boy, who lost his life in the stampede that ensued when the police assaulted a group of peacefully protesting people in Varanasi. There are many more such stories where innocent civilians – mostly Muslims – have borne the brunt of unprovoked police violence. The Muslim slant in police action is all too visible and this has created a huge dent in the reliability of law-enforcement agencies in Uttar Pradesh. Many police officers have stated off the record that they were under instructions to punish protesters with exemplary ferocity so that they would never dare to take to the streets again.

What was one small step for Amit Shah—who piloted the Bill in Parliament—is a giant leap backwards for India. India will no longer be the same. The Republic’s essence will dissipate from carrying the burden of a moral reprehensibility foisted upon its soul by its own parliament. This newly minted Act, which awaits judicial scrutiny on 22 January 2020, is arguably the single most mischievous piece of legislation to have ever passed the halls of Parliament. It is designed to wreck the “basic structure”[2] of the Indian constitution, subvert the essential nature of India, and on the sly, prepare for the formal inauguration of a Hindu Rashtra (Hindu nation).

The Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 provides an accelerated path to citizenship for persons belonging to Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi and Christian communities from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan who came to India on or before 31 December 2014 but were treated as “illegal migrants” as per the existing provisions of the law. The Act ostensibly, as the statement of objects and reasons[3] clarifies, provides sanctuary and citizenship to “religiously persecuted minorities” in the three mentioned countries, which have Islam as the declared state religion. However, the Act omits Muslims from its purview. For the first time in the history of independent India, a religious test has been introduced for the purposes of citizenship.

The Citizenship (Amendment) Act will have to ward off challenges to its constitutionality in the Supreme Court. Does an act, which selectively makes religion a determinant of citizenship, violate the basic tenets of the Indian Constitution? The Indian courts do not inspire the same confidence anymore. In the recent past, a slew of questionable judgements, especially the Ayodhya verdict, have hung a cloud over their independence. It is increasingly obvious that they have chosen to ride with the rising tide of Hindu majoritarianism instead of courageously arresting its flow and upholding the Constitution.

It is a measure of the distance we have traveled since our founding as a republic that today religion has become a factor in the law[4] and affects the understanding of citizenship in India. On 17 October 1949, an amendment was moved by H. V. Kamath in the Constituent Assembly to begin the Preamble with the phrase “In the name of God”.[5] However, this amendment was rejected and prominent among those who opposed it were Rajendra Prasad and Dr. Ambedkar. Our Constitution, therefore, in the imagination of our founders, was secular although the word “secular”[6] itself was not part of the Preamble until 1976.

Even beyond the confines of constitutional propriety, the CAA deeply militates against the civilizational grain of India and its cultural ethos. India has always been a land of diversity built over centuries by a gradual absorption of peoples and faiths from around the world, who found refuge here and became indistinguishable from her bone and marrow. India has always prided itself on the philosophy of vasudhaiva kutumbakam—the world is one family—informing the Hindu traditions of tolerance, which echoed in the words of Swami Vivekananda in a speech[7] delivered in Chicago more than a century ago: “I am proud to belong to a nation which has sheltered the persecuted and the refugees of all religions and all nations of the earth.” Isn’t it shameful that our country that once was the repository of the idealism that Vivekananda embodied is yet to sign the Refugee Convention of 1951 and the International Convention on Refugee Protocol, 1967?[9] The Citizenship (Amendment) Act is not just of dubious constitutional credentials, it is also antithetical to the long-cherished values of our civilization.

2

Article 11 of the Indian Constitution empowers the Parliament to make laws with respect to the acquisition and termination of citizenship. In 1955 the Parliament enacted the Citizenship Act that regulated the citizenship framework of India. This Act has been then amended in 1986, 1992, 2003, 2005, 2015, and now in 2019.

This latest amendment is qualitatively different from all other previous ones as the principle of jus soli (citizenship by birth) has given way to the principle of jus sanguinis (citizenship by descent). In India, the framework of citizenship remained, until now, religion-neutral.[10] Part II of the Constitution deals with citizenship; Articles 6 and 7 pertain to the acquisition of citizenship by migrants coming to India from Pakistan, or migrants returning to India from Pakistan after Partition, who were deemed to be citizens of India irrespective of their religion provided they were in India on or before 19 July 1948. For the first time, the 2019 amendment introduces a religious criterion for the acquisition of citizenship.

The Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019, revises and adds to the principal Act in three significant ways. First, it declares that any person belonging to “Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi and Christian” communities from “Afghanistan, Bangladesh or Pakistan” who entered India on or before 31 December 2014 shall not be treated as “illegal migrant” for the purposes of this Act.[11] Second, a new section, 6B, provides amnesty from all legal and criminal proceedings to all people from the mentioned communities.[12] Lastly, the Third Schedule of the principal Act has been amended to reduce the period of residency for grant of citizenship from “not less than 11 years” to “not less than 5 years”.[13]

The Statement of Objects and Reasons[14] that accompanied the Bill in the Lok Sabha briefly explains the justifications in support of the new amendments. Ostensibly, the justification given is that Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Pakistan – where Islam is the state religion – have “religiously persecuted minorities” who flee into India without necessary documents. The existing law treats them as illegal migrants and therefore they are unable to apply for Indian citizenship under section 5 and 6 of the Citizenship Act, 1955. The “abatement” of legal proceedings against illegal migrants of these communities and a reduction of the residency requirement from 11 to 5 years is justified on the ground that a “special regime to govern citizenship matters”[15] is necessary for members of the six identified communities to help them in the acquisition of Indian citizenship “from the date of their entry into India.”[16]

Everything read together, it means that all illegal migrants from the three mentioned countries and belonging to any religion, except Islam, who came to India before 31 December 2014 will be granted Indian citizenship by December 2020 on the grounds that they are persecuted on the basis of religion in their countries of origin.

3

The most damning legal-constitutional critique of the Act is that it violates Article 14 of the Indian Constitution. Article 14 is available to all persons within the territory of India, citizens and non-citizens alike, and it enjoins the state “to not deny to any person equality before the law or the equal protection of the laws.” It is permissible, however, to make special provisions by law for persons who form a “separate and distinct class” provided that such classification is a “reasonable” one based on “intelligible differentia” having “nexus with the object sought to be achieved”[17] by the said law.

How well does the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 meet these requirements? What is the object sought to be achieved by the Act? If it is to provide sanctuary and citizenship to people who are religiously persecuted in the neighborhood, then why is it that Myanmar, Nepal, Bhutan, China and Sri Lanka are not included in the list? If the object of the law is to extend this amnesty to the territories covered by undivided India, then why is Afghanistan included? Is the classification done in the law reasonable? Shia, Ahmadiyya and Jews are also religiously persecuted minorities in some of the named countries, but have been omitted from the list of communities that will benefit from the CAA. Why?

The thin excuse for including only Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan is that these three countries have a declared state religion. However, a law must take into consideration facts as they exist on the ground. There are other well-documented cases of religious persecution: the Rohingyas in Myanmar, Uighurs in China, and Hindus, Christians and Muslims in Sri Lanka. Why should an Indian law claiming to protect people suffering from religious discrimination turn a blind eye to other instances of proven atrocities based on religion? Is it just because these communities happen to be Muslim? The government seems to be going to unimaginable lengths to exclude Muslims from the ambit of the legislation.

The classification of countries of origin and communities mentioned in the law is neither reasonable nor rational. On the contrary, it appears arbitrarily made to serve the ulterior motive of selectively granting citizenship with the exclusion of Muslims. It is parochial, and the classification is not based on “intelligible differentia” which is the necessary requirement under Article 14 to stand the test of judicial scrutiny.

Finally, the classification of communities and countries of origin is tailor-made to confer citizenship to all non-Muslim illegal migrants. The question is what are the relevant criteria for granting citizenship? Can it be religion? The reasonableness of the classification must satisfy the principle of “intelligible differentia”—which literally means a difference that can be understood— and cannot be based on “arbitrary, artificial or evasive considerations.” [18] The considerations have to be consistent whereas the classificatory schema incorporated in the CAA 2019 is both arbitrary and evasive: countries of origin are selected arbitrarily and it is evasive on the issue of communities facing religious persecution.

The law violates the principle that “Equals must be treated equally and unequals must be treated unequally.”[19] As an example, let us assume that two people, a Christian and a Jewish person, have fled Pakistan because of religious persecution and migrated to India before 31 December 2014. Since both have faced religious persecution, they are “equal” in their circumstances; but the law, as it stands today, will not treat them equally. The Christian will be granted Indian citizenship whereas the Jewish person will be declared an illegal migrant. A Shia, or an Ahmadiyya, or a Hazara will meet the same fate as the Jewish person. The more one puts this law to test, the more contradictory, narrower and sectarian it appears.

The Supreme Court might invoke the “theory of the basic structure”[20] to strike down discriminatory provisions of the CAA 2019. At the time of writing no fewer than 14 petitions against this Act have been accepted by the Court. Prominent MPs like Jairam Ramesh of the Congress Party, Mahua Moitra of the Trinamool Congress, Asaddudin Owaisi of the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMM) are among the petitioners. Many leading scholars of Law and some former judges of the Supreme Court—Justice Madan B. Lokur, Justice Santosh Hegde and Justice R.M. Lodha among those— have argued that the CAA violates the basic structure of the Constitution of which secularism is an inalienable part. Can a secular state grant citizenship selectively based on religion? Isn’t it incumbent upon the state to treat persons of all religions equally and not discriminate among them? The CAA discriminates between religious groups under the guise of providing relief to persecuted minorities from the three countries of origin.

In recent years Indian courts have developed a new doctrine of constitutional morality. Alarmingly for some jurists, this new doctrine has been profusely applied by the courts in many landmark judgements including the reading down of section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, granting entry to women in the Sabrimala temple, the Triple Talaq case, and the Right to Privacy judgement.[22] While there is no express provision in the Constitution for constitutional morality, the Supreme Court under article 142 has wide ranging powers to decree on any matter in the interest of “complete justice”. In the recent verdict on the Ayodhya case, the judges invoked Article 142, although not in an expected manner. Nonetheless, if there were ever a fit instance for striking down a piece of legislation and declare it null and void on the grounds of “constitutional morality” and for the sake of doing “complete justice”, it is the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019.

4

The Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 cannot be understood fully unless it is situated in the political context arising out of the updating and publication of the National Register of Citizens (NRC) in Assam. The BJP stormed to power in Assam in 2016 on the promise of expelling Bangladeshi “infiltrators”. The Assam Accord signed in 1985 defined as an “illegal migrant” a foreigner who came to Assam on or after 25 March 1971.[23] In 2014, on a petition filed by the NGO Assam Public Works, the Supreme Court directed the Assam state government to update the NRC in Assam. The updating began in 2015, and after the final round of scrutiny, the names of 1.9 million people were missing from the register when it was published in 2019. It has been reported that more than half of those excluded from the NRC are Hindus and people belonging to indigenous tribes. This has put the BJP in a difficult bind: while initially supported whole-heartedly by most Bengali/Bangladeshi Hindus in Assam, as it now stands the NRC would lead to their disenfranchisement – something that will not be in the electoral interests of the ruling party.

Viewed from the above perspective, it is obvious that a prime motivation for the BJP to steamroll the Parliament into making a law like the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019, was to save Bengali/Bangladeshi Hindus from being identified as “illegal immigrants”. In the BJP’s terminology such a description fits a Muslim alone whereas a Hindu who migrates is a “refugee” ostensibly fleeing from religious persecution, although the real reason could very well be economic. This law now brings sanctity to the lexicon that BJP has employed for many years in the North East.

The BJP, however, failed to anticipate the scale of protests in Assam and other states in the North East against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019. There is a groundswell of opinion against this Act which is being perceived as diluting the promise given to safeguard the cultural and linguistic identity of the Assamese people under Clause 6 of the Assam Accord.[25] Almost all parties in Assam have opposed the law, students and civil society have marched on the streets demonstrating against the Act. The pull of cultural identity has proven to be far more cohesive in the Northeast than the affinities of religion, unlike what the BJP might have expected. The Hindutva agenda has been halted for the time being as the Assamese people have risen to protect their rights as a distinct community. The BJP should have learnt its lesson from the Indo-Pakistan War over the creation of Bangladesh in 1971 based on linguistic nationalism, which best exemplifies how identities are not cast in stone. While the people of Assam may have flirted with Hindutva, catapulting the BJP to power, the call of cultural and linguistic solidarity has galvanized them to stand against a law that seeks to submerge their particularities in a monolithic and universalist narrative of Hinduness.

The other major bone of contention is that while 25 March 1971 was the cut-off date decided in the Assam Accord of 1985 to determine who was an illegal immigrant, the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 extends the date to 31 December 2014.[26] This implies that almost every non-Muslim migrant in Assam shall become a citizen of India with voting rights, and the fear is that this will create ethnic imbalances in the demographic topography of Assam. It is no wonder that the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 is perceived as BJP’s betrayal of the letter and spirit of the Assam Accord. Despite assurances by Amit Shah, the agitation in Assam has shown no signs of abating yet.

That the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019, expressly states that these provisions shall not apply to the tribal areas of Assam, Meghalaya, Mizoram or Tripura as included in the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution and in the area covered under the “Inner Line Permit System.”[27] The Government has made a further conciliatory move by extending the Inner Line Permit Regime—which allows the authorities to regulate the travel and stay of outsiders in designated areas—to Manipur. Yet, these measures haven’t been enough to assuage the people from the Northeast, who feel that their cultural identity will be threatened by immigrants who will now become citizens under the new law.

5

The Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 is riddled with political and social contradictions and fraught with possible constitutional impropriety. To those who believe that people of the same religion cannot persecute their co-religionists, they only have to look at the history of Europe where Catholics and Protestants fought bloody wars, or the history of Islam where the Sunni-Shia conflict has consumed countless lives. They can also look at India where caste atrocities of the most despicable kind have shaken any belief in the fact that having the same religion makes one immune to discrimination and cruelty. The Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 could have recognized all kinds of persecution based on political beliefs, sexual orientation, gender, and other markers, including religious persecution of denominations within the same religion. It hasn’t. Why did the BJP privilege inter-religious persecution over other kinds of persecution on the basis of intra-religious, economic, gendered persecutions, or persecution on the basis of sexual identity and orientation?

These gaping loopholes make one question the sincerity of the government towards the declared objectives of this Act. The most ominous implication of the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 emerges not in its letter, but when one reads it along with the possibility of a nation-wide NRC. From the vantage point of Muslims, a 200-million strong minority in India, even a genuine failure to prove citizenship on account of loss of documents, or a lack of them, will mean the loss of citizenship. India is a woefully undocumented country: the poor, the landless and those on the margins have neither the wherewithal to procure documents nor a sympathetic state to hold their hand. They also cannot afford to create the required documentation as it involves traveling long distances on their own expense to different State offices. The specter of statelessness looms on the horizon for a large section of the population. In the current political climate, such undocumented people will also have to face the ire of public opinion which has been systematically poisoned by BJP through persistent use of terms like “termites” and “infiltrators”. The Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 and the NRC are twin weapons of whipping up communal frenzy and reducing Muslims to second-class citizens in their own country. The BJP understands the explosive potential of these legislative and administrative tools and it will leave no stone unturned to milk them for all their worth.

In brief, against the current of history—which is a testimony to the expansion of citizenship rights to larger number of people—the government is attempting to terrorize Muslims with the threat of statelessness through the diabolical marriage of the proposed NRC with the new citizenship law which provides umbrella immunity to all non-Muslims.

The Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 is a regressive and dangerous ploy to awaken the demon of communalization. We must not be fooled by homilies that abound regarding saving people from religious persecution. There is much more to this new law than meets the eye if only we can see through how it has already been deployed in the ongoing political discourse, and how it has been used by Amit Shah and Modi in their speeches to identify people protesting against it with a specific religion. The police brutalities on students, the disproportionate use of force in Jamia Millia Islamia and Aligarh Muslim University and in Uttar Pradesh are another attempt to signal that it is only Muslims who will have a quarrel with the new law.

The original design of the Constitution was based on a conception of a civic and national idea of citizenship which was religion-neutral. The Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 is a determined push to change the nature of citizenship by imbuing it with ethnic-religious colors. This very well may be the opening salvo of the preamble of a Hindu Rashtra eager to unleash itself, anxious to be born.

[1] The opening lines of Nehru’s historic address: “Long years ago, we made a tryst with destiny, and now the time comes when we shall redeem our pledge, not wholly or in full measure, but very substantially. At the stroke of the midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom. A moment comes, which comes but rarely in history, when we step out from the old to new, when an age ends, and when the soul of a nation, long suppressed, finds utterance…”

[2] The Supreme Court in the famous Keshvanand Bharti Case, 1973, developed the doctrine of the basic structure of the Constitution which has since been used in many subsequent judgements to strike down amendments & laws passed by legislatures.

[3] Bill No. 370 of 2019, Statement of Objects and Reasons, pp. 4-5

[4] Article 11 of the Constitution empowers the Parliament to make laws with respect to the acquisition and termination of citizenship pursuant to which the Parliament enacted the Citizenship Act, 1955. The Act has been amended many times since.

[5] Secularism & Constituent Assembly Debates, 1946-1950, EPW, July 27, 2002, by Shefali Jha

[6] The word Secular was inserted in the Preamble by the 42nd Amendment, 1976

[7] See Vivekananda’s address to the World Parliament of Religions, Chicago, 11th September, 1893.

[8] It is a United Nations multilateral treaty signed by 145 countries defining the rights of refugees and the responsibilities of countries granting asylum.

[9] It is a United Nations multilateral treaty signed by more than 146 countries to secure the rights of refugees anywhere in the world.

[10] Niraja Gopal Jayal argues along these lines in her essay ‘Faith based Citizenship’; www.TheIndiaForum.in, November 1, 2019

[11] see THE CITIZENSHIP (AMENDMENT) ACT, 2019 NO. 47 OF 2019; This proviso has been added in section 2, sub-section (1), clause (b) of the principal Act (1955)

[12] Section 6B, Clause (3); THE CITIZENSHIP (AMENDMENT) ACT, 2019 NO. 47 OF 2019

[13] See amendment done to the Third Schedule of the principal Act by THE CITIZENSHIP (AMENDMENT) ACT, 2019 NO. 47 OF 2019

[14] Bill No. 370 of 2019, Statement of Objects and Reasons, pp. 4-5

[15] ibid

[16] ibid

[17] See John Vallamattom v. Union of India, AIR 2003 SC 2902

[18] See Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India, 1978

[19] This is an old Aristotelian principle which is now an accepted legal maxim the world over.

[20] The Supreme Court in the famous Keshvanand Bharti Case, 1973, developed the doctrine of the basic structure of the Constitution which has since been used in many subsequent judgements to strike down amendments & laws passed by legislatures.

[21] https://scroll.in/latest/946370/citizenship-bill-former-judges-say-classification-on-religion-language-not-reasonable

[22] https://barandbench.com/constitutional-morality-india-new-kid-block/

[23] See Clause 5.8 of the Assam Accord, 1985 signed between the Government of India, the AASU & AAGSP.

[24] https://theprint.in/india/bengali-hindus-in-assam-look-at-citizenship-bill-to-get-out-of-nrc-mess/287076/

[25] Clause 6 of the Assam Accord: “Constitutional, legislative and administrative safeguards, as may be appropriate shall be provided to protect, preserve and promote the culture, social, linguistic identity and heritage of the Assamese people”.

[26] see THE CITIZENSHIP (AMENDMENT) ACT, 2019 NO. 47 OF 2019; This proviso has been added in section 2, sub-section (1), clause (b) of the principal Act (1955)

[27] See Clause 6B (4) of THE CITIZENSHIP (AMENDMENT) ACT, 2019 NO. 47 OF 2019