In Kashmir’s frigid winter a woman leaves her door cracked open, waiting for the return of her only son. Every month in a public park in Srinagar, a child remembers her father as she joins her mother in collective mourning. The activist women who form the Association of the Parents of the Disappeared Persons (APDP) keep public attention focused on the 8,000 to 10,000 Kashmiri men disappeared by the Indian government forces since 1989. Surrounded by Indian troops, international photojournalists, and curious onlookers, the APDP activists cry, lament, and sing while holding photos and files documenting the lives of their disappeared loved ones. In this radical departure from traditionally private rituals of mourning, they create a spectacle of mourning that combats the government’s threatening silence about the fates of their sons, husbands, and fathers.

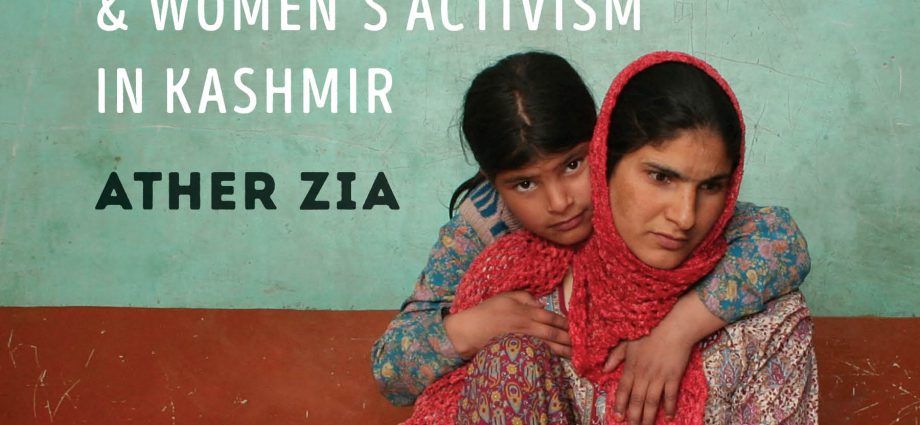

Drawn from Ather Zia’s ten years of engagement with the APDP as an anthropologist and fellow Kashmiri activist, Resisting Disappearance follows mothers and “half-widows” as they step boldly into courts, military camps, and morgues in search of their disappeared kin. Through an amalgam of ethnography, poetry, and photography, Zia illuminates how dynamics of gender and trauma in Kashmir have been transformed in the face of South Asia’s longest-running conflict, providing profound insight into how Kashmiri women and men nurture a politics of resistance while facing increasing military violence under India.

Excerpted with permission from the book, Resisting Disappearance: Military Occupation and Women’s Activism in Kashmir

I first met Shabir Mir, a slight and painfully polite man, when he was looking to consult doctors for a chronic wound in his abdo- men, the result of torture at the hands of the Indian army. Shabir is pivotal to this ethnography because he experienced being disappeared. He had been in the custody of the Indian army for twenty-eight months during which his family knew nothing of his whereabouts. His predicament illus- trates how the Indian nation-state constructs bodies that are seen as fit to be eliminated without accountability. Shabir recalled that the soldiers, while torturing him, encouraged each other by saying, “Harami ko azadi chahiye, aukaat to dekho saley ki? Iss desh drohi ko maut dedo; azadi mill jayegi; kodey mein dalo, ye sab saley deshdrohi hain, dedo inko azadi [This bastard wants freedom (from India). What audacity! Kill the bloody traitor; give him freedom (from life); throw him in the trash; they (Kashmiris) all are sisterfucking traitors; give them freedom (from this world)].”

This passage encapsulates how a Kashmiri body is socially and politically constructed and perceived by the Indian military occupiers. In the state of exception, created by the Indian military occupation in Kashmir, the legal order operates only by suspending the law itself. This suspension becomes the rule and the law in force without significance, as Giorgio Agamben (2005) has reminded us. Shabir’s experiences inside the secret prison illus- trate how the “killability” of the Kashmiri body is justified. The killable Kashmiri body (Zia 2018)—one that can be killed without remorse or accountability—is the turf on which the spectacle of power is staged by the Indian nation-state. This language hurled by the soldiers at Shabir is not unique and has been heard by most Kashmiris in different iterations, the sum of which marks them as the “Other” fit to be killed because they desire liberation from India. Shabir’s life story is an exemplar of Kashmiri haplessness.

MAKING THE OTHER

In 1991, Shabir was detained under false allegations of being a militant. According to his wife, Taja, Shabir became gaeb (disappeared) in custody, and she began the frantic ritual of searching for him. The army and police denied he was in their custody. Then, one random evening, two years and four months later, Shabir was found comatose, abandoned in a school build- ing that had been used as a makeshift camp–cum–interrogation center by the army. Shabir had a ruptured abdomen, his rectum was infected, and wounds festered all over his body. Emaciated and severely injured, he survived but only after many corrective surgeries. He nevertheless ended up with severe disabilities. Most often, men who are forcibly disappeared are never found, and Shabir’s return was nothing short of a miracle for his family.

Shabir recalled the torture inflicted on his body. His pain would be multiplied when the soldiers administered a mix of water, chile, and electricity to his wounds. “They [Indian soldiers] would electrocute me; I lay writhing. . . . Torture in the night was the worst because they would get drunk; that’s when most boys would get killed. They would beat us nonstop; some boys just died like that.” Shabir had been taken to the brink of death many times. He recounted the experience:

My survival is a miracle. I thought every night was my last. A wounded boy once begged for water while taking his last breaths. I dragged myself near him. Such was his thirst that he pleaded for me to spit into his mouth, and I did. Despite this being a nasty act, the boy looked thankful and closed his eyes. The next day, his body was gone. I do not know if someone found him or not. From what I could guess, we were somewhere on an elevation, with trees around; maybe they just dumped the bodies, and they would never be found and would be disappeared forever.

How can this torture be explained? Scholars have documented how, in varied ways, nationalism is constructed on the body, which becomes a literal and metaphorical vehicle for people’s collective fears, hopes, and commitments. The nation-state appears by asserting itself through the habitual performance of power, where it prevails physically and symbolically over people? How can this torture be explained? Scholars have documented how, in varied ways, nationalism is constructed on the body, which becomes a literal and metaphorical vehicle for people’s collective fears, hopes, and commitments. The nation-state appears by asserting itself through the habitual performance of power, where it prevails physically and symbolically over people (Aretxaga 1997). Shabir’s predicament becomes symbolic of how the Indian government’s insignia is branded on the Kashmiri body, even when the body is made invisible or disappeared altogether. Many scholars have detailed the brutality of the Indian government’s policies in Kashmir (Kazi 2009; Duschinski 2010; N. Kaul 2011; Bhan 2013; Verma 2016; Robin- son 2013; Snedden 2013; Mathur 2016; S. Kaul 2017; Duschinski et al. 2018). The Indian administration has been called “catastrophic,” which has made people’s lives subservient to consolidating borders and state security, paving the way for their annihilation or destruction (Bhan 2013: 7; Duschinski and Hoffman 2011a, 2014; C. Mahmood 2000). International watchdogs, such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, have issued reports criticizing India and claiming that it has lost its moral ground in integrating Kashmir into its borders (Kumar 2010). In 2018 the UN’s Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights published a historic report assessing the human rights situation in Kashmir. The report marks the beginning of a potentially momentous shift in the international human rights community’s recognition of Kashmiri people’s situation and aspirations in this underreported war zone.

Under the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA, implemented in 1991), every Kashmiri is a potential suspect. Anyone can be stopped, or even shot, without any explanation. Thus, day in and day out, Kashmiris are subjected to unmediated power, where everyone is effectively reduced to the status of killable. The icon of Shabir’s body in the context of the phrase hurled at him by the soldiers (mentioned at the beginning of the chapter) becomes an analytic for understanding the killable body. The Kashmiri body as killable is constructed from all the stereotypical markers of the Other—both material and immaterial. In the immaterial form the markers around the Kashmiri body are discursive categories, like the demand for nationhood, which, emptied of its history, is seen as traitorous by the Indian government, its army, and its citizens. The armed militancy is decontextual- ized from the events preceding 1947, portrayed only as propensity for vio- lence fueled by global terrorism. The affective relationship that Kashmiris have with Pakistan through a shared historical, geographical, cultural, and religious heritage has also led to this Othering. India projects Kashmir’s historical ties with Pakistan as unnatural.

The Kashmiri body, in the Indian perception, is cast primarily as the Other—a Muslim and, by extension, even a Pakistani or a traitor body. The body with “certain Otherness,” which can harm the nation, makes it possible for the government to carry out extrajudicial abuses. In material form the type of dress and demeanor of a person becomes suspect. The keffiyeh (typically a Palestinian scarf or its South Asian version), beard, kohled eyes, and carrying a Quran or Urdu or Arabic scriptures are seen as part of a habitude that foretells of an “Islamist,” “radical,” “pro- freedom,” “pro-Pakistan,” or “fundamentalist”—all terms that are used stereotypically to insinuate militant influences drawn from Islamic principles. In Kashmir fearful families often discourage young men from adhering to such dress or demeanor, and even to avoid having a beard, to avoid endangering their lives. It is telling that 99 percent of the disappeared men in Kashmir have been civilian Muslim males, with most of them being bearded (Choudhury and Moser-Puangsuwan 2007). These material markers appear as what Lisa Malkki (1995) has called “body-maps,” which demarcate the enemy’s body from oneself (see Weiss 2004). These bodymaps are reinforced in the public narrative, especially by the media. The Kashmiri body, in the Indian perception, is cast primarily as the Other—a Muslim and, by extension, even a Pakistani or a traitor body. The body with “certain Otherness,” which can harm the nation, makes it possible for the government to carry out extrajudicial abuses (Kumar 2010).

The Otherness of Kashmiris, the majority of whom are Muslim, is also connected to the trope of Muslim deviance that proliferates in the Indian polity. In many versions of the aforementioned quote, Shabir heard himself being branded a “Pakistani,” even though he believes in an Independent Kashmir. This labeling comes from the Indian fear about the overarching affective allegiance of Kashmiris to Pakistan—a country with which a faction wants to merge—but it also stands as a proxy for everything that is perceived as Other, including those desirous of separate nationhood. The Otherness of Kashmiris, the majority of whom are Muslim, is also connected to the trope of Muslim deviance that proliferates in the Indian polity. Historically, Muslims in India (and not just Kashmiri Muslims) have been cast as a volatile group. The communal tensions between majority Hindus and minority Muslims have fueled many pogroms and massacres (see Nussbaum 2007). In general, the perception of Indian Muslims, even if they did not choose to go with Pakistan in 1947, is of the Other in India. Thus the hypervisibility of the Kashmiri body increases because it is not only a Kashmiri body but also a Muslim body, making it doubly killable.

In the hands of a nation-state, the killable body becomes useful for creating an easily identifiable enemy: a traitor, a deviant for the masses, who unite against it. The act of killing Kashmiris has even been narrativized in the media as a “habit” of the Indian soldiers. Reminiscent of Damien’s public execution in 1757 after he attacked the king in Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish (1977a), a similarly killable Kashmiri body is made into an identifiable and representational threat for dissenters. In the hands of a nation-state, the killable body becomes useful for creating an easily identifiable enemy: a traitor, a deviant for the masses, who unite against it. The act of killing Kashmiris has even been narrativized in the media as a “habit” of the Indian soldiers. The landmark case of a former Kashmiri militant, Afzal Guru, who was indicted in the 2001 attack on the Indian Parliament, is illustrative of how a killable Kashmiri body, once constructed, can be fair game, even for being hanged. Even though we can argue that the cases of Guru and Shabir are different, both are symbolic of how a Muslim Kashmiri body is made killable under law. Even though Guru’s case was weak, containing only circumstantial evidence, he was hanged in 2013 for what the Supreme Court of India openly called an act to satisfy “the collective conscience” of the Indian society (“Supreme Court Judgement on Afzal Guru” 2013). Juridical power, time and again, appears as a result of a political approach to national security (Saumya 2009).

The act of forcible disappearances, killing, maiming or blinding is an annihilating warning to all those potentially subversive Kashmiris. Even after Shabir returned from incommunicado detention, for instance, his tortured and chronically wounded body continued to carry the insignia of the Indian state’s coercive sovereign power. Guru was constructed as an exemplary killable Kashmiri body on which the spectacle of the sovereign power of the Indian state played out (Zia 2018). His media trial, his portrayal in public, the lack of legal amenities, and his Muslimness and Kashmiriness all contributed to his construction into an adversary whom the Indian nation made sure to annihilate (ibid.). Thus, in this context, the killability of the Kashmiri body is manifested as a singular act of nation-making. As human rights lawyer Parvez Imroz put it: “They can disappear anyone: me while I am talking to you or even you . . . anyone can be killed or disappeared at any time, without reason.” This fear is often expressed by Kashmiris. The act of forcible disappearances, killing, maiming or blinding is an annihilating warning to all those potentially subversive Kashmiris. Even after Shabir returned from incommunicado detention, for instance, his tortured and chronically wounded body continued to carry the insignia of the Indian state’s coercive sovereign power.

Since 1947, the region of Kashmir has been caught in an ebb and flow of both visible and invisible forms of violence. Stereotypically presenting Kashmir as a dispute between India and Pakistan is a reductionist view, which neglects the Kashmiri people’s aspirations for a sovereign nationhood that predates the partition of British India and the Princely States. Since 1947, the region of Kashmir has been caught in an ebb and flow of both visible and invisible forms of violence. Stereotypically presenting Kashmir as a dispute between India and Pakistan is a reductionist view, which neglects the Kashmiri people’s aspirations for a sovereign nationhood that predates the partition of British India and the Princely States. Since then, India has legitimized its military occupation of Kashmir by deploying a politics of democracy. I use the phrase “politics of democracy” to emphasize that it is not democracy in its true form that exists in Kashmir, but rather the symbols of democracy, such as the “elections” that have been utilized to entrench and extend Indian rule. In this context, democracy becomes a tool to “serve territorial nationalism” (Junaid 2013a: 166). A chronology of events pertaining to the contesting Indo-Pak nationalisms over Kashmir illuminates how the postcolonial nation-state of India established and legitimized a military occupation in Kashmir (Osuri 2017; Bhan, Duschinski, and Zia 2018). Under these conditions, suspending the basic human rights of Kashmiris, as illustrated by Shabir’s experience, and suppression of dissent by government forces with impunity became a norm.

In 1931 in the Princely State of Jammu and Kashmir a key incident occurred when the Kashmiri Muslims revolted against the Hindu monarch Hari Singh of the Dogra dynasty. During a mass demonstration, the king’s police killed twenty-two Kashmiris. Today the historical martyrs’ graveyard dedicated to these men stands as a testament to Kashmir’s aspiration for an independent sovereign democracy. At the time of the massacre, almost a century had passed since 1846, when the British colonial government had sold the entire region of Kashmir to Hari Singh’s warlord ancestor Gulab Singh. The British colonizers had imposed territorial and administrative unity over the disparate geographical and cultural provinces— namely, Kashmir, Jammu, Ladakh, and allied regions—jointly referred to as the Princely State of Jammu and Kashmir. Gulab Singh bought the territory along with its people for seventy-five thousand Nanak Shahi rupees and an annual present of one horse, twelve shawl goats, and three pairs of the finest Kashmiri shawls to the British Crown. The hundred years of Hindu Dogra rule were ruthless for the majority of the Muslim Kashmiris who lived in de facto slavery. This period became generative of political and economic awakening in the Kashmiri people (Rai 2004; Zutshi 2003). In 1932 newly educated young Muslim men forged a political movement to fight for people’s rights and ultimately gain democratic sovereignty.

The dispute over Kashmir between India and Pakistan began with the 1947 Indo-Pak partition, which was predicated on religious difference. While nominally secular, India became a Hindu-majority nation, and Pakistan became a homeland for Muslims. Dominantly Muslim, Kashmir was largely expected to integrate with the newly formed Pakistan with which it had geographic contiguity, trade, and cultural links. The monarch of Kashmir was indecisive about acceding to either country and wanted to explore the option of independence. Meanwhile, he signed a “standstill” agreement with Paki- stan to ensure that essential services—trade, travel, and communication— remain uninterrupted. Pakistan saw this as a forerunner to the accession and its indisputable claim to the region. The Indian leaders had started their diplomacy to acquire Kashmir long before 1947 (Noorani 2014). The majority of Kashmiris at that time preferred to stay independent and not join either of the two countries (see Whitehead 2008: 26–27).

From August 15, 1947, when India and Pakistan became two dominions, until October 27, 1947, when the Indian military landed by plane, Kashmir was an independent state. By then the Indo-Pak partition had descended into communal violence. In the region of Poonch in West Kashmir, an armed revolt was building under the name of Azad (Independent) Kashmir Regular Forces (Duschinski et al. 2018) to create an independent state (Lamb 1991; Snedden 2013). The king suppressed the revolt brutally, but the rebels successfully liberated part of the region declaring the Azad (Independent) Kashmir provisional government on October 24, 1947. By this time the communal violence of the Indo-Pak partition spilled into Kash- mir’s Jammu province. Approximately two hundred thousand Muslims were killed in an ethnic cleansing that the king endorsed (Lamb 1991; Howley 1991; Copland 2005; Lone 2009).

In the Indian narrative what followed the Poonch revolt is called an “invasion by Pakistan” or pejoratively the “Qabaili raid,” referring to the ethnic clansmen who came to Kashmir’s aid from the North West Frontier Provinces (NWFP) of the newly founded Pakistan to aid the Poonch revolutionaries. The ethnic clansmen had long-standing family, cultural, and trade ties with the people in Poonch, and they were impassioned to fight alongside their co-religionists against the impunity of the Hindu king. Fear- ing loss of territory, the king asked India for military support. The Indian government agreed with the precondition that the king accede to India and promised to hold a plebiscite to decide the region’s final fate. The king agreed to a treaty of accession for the entire Princely State, retaining control in all matters except defense, currency, and foreign affairs.

In 1948, after the first full-scale war broke out between India and Pakistan over Kashmir, India took the issue to the United Nations, where it repeated its commitment to a plebiscite. The UN brokered a 485-mile-long ceasefire line that split the region in two. One-third of the territory, including the far northern and western areas along with Gilgit-Baltistan, ended as a semiautonomous entity administered by Pakistan, known as Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK).10 The remaining two-thirds of the region, including the valley of Kashmir and the provinces of Jammu and Ladakh, came under Indian control.11 The promised plebiscite was never held.

The Indian narrative since 1947 has dominated explanations of the Kash- mir dispute in which violence by the militia from the NWFP is made hypervisible and a vested silence is maintained on the barbarity of its own military (Lamb 1991: 143). Revisionist scholars have challenged India’s arguments, especially those that obfuscate Kashmir’s historical demand for a democratic sovereignty by varyingly presenting the Kashmir issue as Pakistan’s proxy war, or reducing it to the erroneous stereotype of “Islamic terrorism” and relegating it to a domestic law-and-order situation. Exhaustive analysis of events surrounding the Indo-Pak partition, when borders were in flux and people’s loyalties had not concretized, has established that India was no less an aggressor (Lamb 1991; Schofield 1996; Osuri 2017); there is a discrepancy in the signing of the treaty of accession with India (Lamb 1991; Schofield 1996, 2004) and the Poonch uprising was a revolt, not an invasion (Lamb 1991; Snedden 2013). In light of the liberation of the Azad Kashmir region, questions are even being raised on the validity of the king acceding the entire Princely State to India (Lamb 1991; Snedden 2013).

ELECTIONS AS POLITICS

The United Nations responded to the status quo between the countries by forming the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan (UNCIP).12 Later, a Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP) was deployed, which continues to monitor the cease-fire in the region. In 1949 UNCIP recommended handing over the region to a quasi-sovereign power of the plebiscite administrator. The UN crafted several plebiscite models, all of which failed due to the competing preconditions put forth by the two rival countries. In 1951, India concertedly began a policy of legitimizing its military occupation by establishing a permanent government through holding elections for a constituent assembly. The mechanism of constituent assembly had been used under the British rule to draft the constitution of India and had also served as the first parliament. Pakistan protested, arguing that India was planning to finalize the accession, which India denied.

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) warned India “that the assembly might conflict with its recommendations still sub judice and deemed the course of action out of order” (Lamb 1991: 175). But India went ahead and conducted the ill-founded elections, which were rigged in favor of a Kashmiri political party that sided with India. The UN dispatched several mediators to investigate the election malpractice and continued exploring options for demilitarization and a plebiscite. After 1954, Cold War rivalries froze the Kashmir dispute. Further international mediations failed, sidelining both the UN and the voice of the Kashmiri people. The Indian government continued its policy of legal annexation, issuing a presidential order that extended Indian citizenship and the fundamental rights charter to Kashmir (Lamb 1991; Bose 2004). This charter is one of the Trojan horses of India’s policy, which is unique in permitting preventive detention to curb threats to national sovereignty or public order. This policy enabled the Indian government to curb dissent against it inside Kashmir (Noorani 2011; Duschinski and Ghosh 2017). Thus India’s coercive policy of legitimizing its governance through legal rulings and paring Kashmir’s autonomy was well underway. Haley Duschinski and Shrimoyee Ghosh (2017: 314) have called this “occupational constitutionalism” a form of legal incorporation of Kashmir that “became sedimented through the work of the courts across time.”

India has historically propagated the notion that the 1951 and successive elections are proof of Kashmiri endorsement of the accession treaty, thereby negating the need for a plebiscite. This narrative conveniently obfuscates the analysis that calls its electoral democracy “subverted and permanently retarded” (Bose 1998: 27) and “flawed” (Navlakha 2009), which has only been successful through rigging to prop up predetermined candidates who favor Indian accession (Bazaz 1978; Lamb 1991; Noorani 2014). India intended to rule Kashmir as a party state (Bose 1998), and those perceived in any measure adverse to expanding Indian constitutional jurisdiction have been disqualified for insubstantial reasons or harassed or imprisoned. The elections held in 1962, 1967, and 1972 were also brazenly rigged (Nehru 1997; Bose 2004) and ultimately completely sidelined the movement for a plebiscite. In 1964, India further eroded Kashmir’s special status to bring it to par with its other states. Kashmiri people responded with angry protests, which the government put down with brutal force. The 1960s saw the rise of the Al-Fatah armed movement for the independence of Kash- mir, which the Indian government repressed in under a decade. By the 1970s the incarceration of the local leadership and coercive politics ensured that opposition to Indian expansion policies was severely undermined.

The year 1987 was a watershed moment. Many notable Kashmiris, who wanted to raise the question of political dispute of Kashmir under the UN mandate, decided to stand for elections under the banner of the Muslim United Front (MUF).15 Despite popular support, the MUF lost after massive and concerted rigging by a party that unsurprisingly favored India. In the protests that ensued, government forces killed four people and arrested the MUF cadre. Some analysts propagate the idea that the Kashmiris resorted to arms because India did not allow democracy to flourish in Kashmir (see Behera 2006). However, my interviews with former MUF supporters indicate that the electoral loss only shifted their policy of participatory politics. Their primary intention had not been governance but to gain control of the assembly and revive the Kashmiri demand for self-determination and independence. Thus the seeds of the Tehreek (the resistance movement against Indian rule) were sown long before but “did not come to fruition until 1988– 89” (Lamb 1991: 336).

Since 1947, the right to dissent in Kashmir has been curbed. People can- not network and organize to pursue their ideals of self-determination and independence in a lawful manner. The only political parties that have permission and patronage from the government are pro-India. Currently, most of the leaders of the Tehreek, who are part of the Hurriyet (Freedom) Conference (a conglomerate of twenty-eight political resistance parties formed in 1991), are often incarcerated, harassed, and placed under restrictions. Recent years have seen increased attacks on the media through censorship, and journalists are often beaten or harassed (Reporters Without Borders 2013). Full-fledged gagging of the local media, the Internet, and mobile phones is recurrent. The undemocratic foundation of the Indian government in Kashmir is evident at no less a time than during elections—a mega- spectacle of its military power over the region. For the initial six years of the armed movement, Kashmir was governed through direct rule from New Delhi, locally called “Governor Raj.” In 1996 elections were held that were unsurprisingly fixed, rigged, and coercive, with a massive presence of government troops. Subsequent elections have been irregular, tedious, and complex, and the presence of government troops is disproportionate and impedes public movement through patrols and curfews (Navlakha 2009). In the 2014 elections, in addition to the existing military force, an additional 56,500 troops from India were sought to control the election process (see “J&K Seeks 56,500 Security Force Personnel” 2014). The army and police are often accused of placing restrictions on people and forcing them to vote (see Bose 2004; Junaid 2013b).

The elections are systematically boycotted by Muslim Kashmiris, partly due to a ban by resistance leaders and militant outfits but also because rigged voting is seen as weak compensation for self-determination. The documented turnout in Srinagar has been as low as 10 percent (Constable 2004). In 2017, following an uprising, voter turnout went down to a mere 7 percent and 2 percent in the elections. Most of my research partners had never voted, and those who did said that they voted for “bijli, sadak, pani [electricity, roads, and water]” (also see Mukherjee 2008). The Kashmiri opinion leaders I interviewed all agreed that two distinct categories of politics exist in Kashmir: one pertains to day-to-day governance, and another to the resolution of the Kashmir dispute. Thus people vote for civil governance. It is not an indication of giving up their demands for self-determination and certainly is not an endorsement of the accession to India.

THE ARMED STRUGGLE OF 1989

By 2000 the armed militancy had abated to a large extent. According to the Indian administration’s own estimates, the number of militants had dropped to fewer than five hundred, yet the counterinsurgency policies continued with full force. From 2008 on, the Kashmiri resistance morphed into a culture of increased civil disobedience. Under the rubric of the Tehreek, the armed resistance is called Askari Tehreek, meaning “armed movement.” This was led by the pioneer organization Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF). Although the outfit started in 1964, it resorted to armed militancy only in the late 1980s. JKLF believes in a sovereign Kashmir, independent from both India and Pakistan. Still, in existence, the group gave up arms in 1994 and works as a political movement. The second most influential group is the Hizbul Mujahidin (HM), which was co-founded by Ahsan Dar, a Kashmiri teacher. HM is dominantly pro-Pakistan and continues to fight in Kashmir. In the 1990s the armed groups numbered anywhere between 44 and 140, with differing goals of joining Pakistan or independence, but all are anti-India. The armed uprising was bolstered by civilian support. Public displays of unity with the militants popularly called Mujahids (“strivers” in Arabic), who were perceived to be fighting a jihad, were rampant.

People participated in protest marches organized in support of the Tehreek, the release of political prisoners, and denouncements of human rights abuses by the Indian forces (Hajni 2008). Women sang songs cheering the militants, and when they were killed in combat, their funerals were massive. Their burials took place in cemeteries designated as Mazar-e-Shuhada (Martyrs Graveyard) (Junaid 2018). Kashmiris also resurrected the long sidelined United Nations as an icon of their aspirations of self-determination and a plebiscite. Massive rallies, at one point “a 400,000 strong crowd, marched to the UN headquarters in Srinagar to hand over memoranda demanding [a] plebiscite” (Schofield 2004: 150).

Most Kashmiris believed that the revolution would be short (Human Rights Watch 2006). But the 1990s wore on without the Tehreek getting closer to any culmination. In the early 1990s the Kashmiri Hindus, known as the Pandits (a 100,000- to 140,000-strong community), migrated en masse from Kashmir to Jammu, Delhi, and other places. Most Pandits, barring some exceptions, have always supported Indian rule. In an atmosphere of distrust and fear, the militants selectively killed prominent Kashmiri personalities who supported India, from both the Muslim and Pandit communities (Bose 1998; Evans 2002). Scholars have noted that the selective killings by the militants were based on politics and not religion (Bose 1998: 74; Hassan 2010: 10), but many Pandits accused the Tehreek of being communal. Muslims blame the political violence and the perception of fear, which was amplified by the government that facilitated the migration (Mohan et al.1990). Counterinsurgency policies intensified, leading to several back-to-back massacres just as Pandits left (Schofield 1996: 246; Donthi 2016). Kashmir became a battlefield. The Indian forces established bunkers and checkpoints everywhere, and combing operations and patrolling became usual affairs. The implementation of the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) resulted in high numbers of killings, disappearances, raids, and rapes, affecting both combatants and noncombatants (see Mishra 2012).

By 2000 the armed militancy had abated to a large extent. According to the Indian administration’s own estimates, the number of militants had dropped to fewer than five hundred, yet the counterinsurgency policies continued with full force. From 2008 on, the Kashmiri resistance morphed into a culture of increased civil disobedience. The protestors banded together under slogans like “Quit Kashmir” and “Go India, Go Back.” Pitched street battles known as kanijung (stone battles), where factions of civilians— mostly youth known as sang baaz (stone-warriors)—fought the government troops. Thus a new phase of the Kashmiri Intifada (H. Khan 1990; Kak 2010) began, bolstered by street art, poetry, e-magazines, and graffiti—what scholars see as “civil society’s indefatigable uprising for freedom” (Chatterji 2010: 133). Hartal (referring to a civil curfew), a long-standing means of protest used by Kashmiris, also intensified.

Civilian uprisings have broken out over the past decade with a marked predictability. A recent uprising started in 2016, after Burhan Wani, a popular twenty-two-year-old militant, was killed in an encounter with Indian forces. In the protests that followed his killing, more than ninety-eight people were killed and over eleven thousand wounded (OHCHR 2018). India downplays the human rights violations, conveniently sidelining the Kashmiri political aspirations for sovereignty that can be traced back a century.

Resisting Disappearance: Military Occupation and Women’s Activism in Kashmir By Ather Zia was published by University of Washington Press (2019).