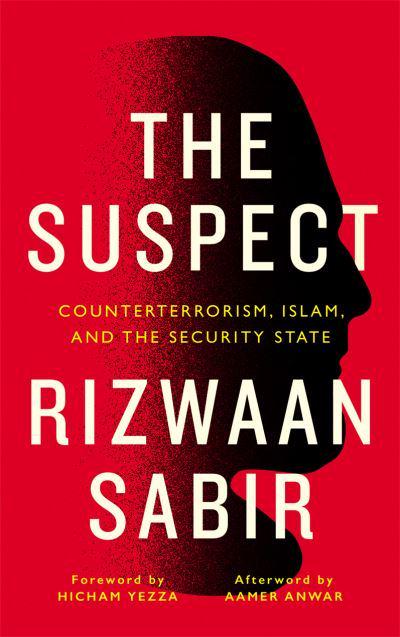

Published by Pluto Press, The Suspect by Rizwaan Sabir draws on the author’s experiences to take the reader on a journey through British counterterrorism practices and the policing of Muslims.

Sabir describes what led to his arrest for suspected terrorism, his time in detention, and the surveillance he was subjected to on release from custody, including stop and search at the roadside, detentions at the border, monitoring by police and government departments, and an attempt by the UK military to recruit him into their psychological warfare unit.

Following is an excerpt from the book.

Withdrawing Consent

When I began researching al-Qaeda for my postgraduate studies, I wanted to understand the group, what they were doing, and what they wanted to achieve. I hoped that I could play a part in identifying the root causes of the group’s violence. After the police arrested, detained, and suspected me of being connected to al-Qaeda myself, and then routinely surveilled, stopped and searched me, however, I felt compelled to refocus my attention and energy towards studying and researching policing and counterterrorism. My goal was now to stop people from being impacted and harmed in the same way that I had been. I was, to put it simply, driven to resist because of the violence of the security state.

The security state recognises that the coercive exercise of power may breed resistance which is why counterinsurgents suggest that rather than relying on overtly violent counterterrorism practices such as, for instance, detentions, bombings, and targeted killings, a mix of less violent and persuasive tactics be used to fight armed Muslim groups and politically control communities. Counter- insurgents recognise that hard coercive power can be politically costly and therefore prefer exercising power through consent. Relying on influence, propaganda, and surveillance, counterinsurgency-infused counterterrorism is likely to be viewed by the public as ‘the lesser of two evils’ and therefore more appropriate than overt violence and force. This allows the security state to exercise power and fulfil its goals with less contestation and resistance.

Using a less violent or different approach to fighting armed Muslim groups and controlling communities enables the state to be seen as a legitimate holder and wielder of power. Carl Von Clausewitz, the eighteenth-century Prussian general and major influence on Western military thinking, makes an interesting point in his book On War in this regard. He writes that the military methods used by nation-states to fight their enemies are only a ‘means’ to securing a bigger objective which is ‘the compulsory submission of the enemy to our will’. Getting your enemy to do what you want, in other words, is more important than what methods and means you use. If it is violence that is required, then it should be employed according to this Clausewitzian reading. If it is rewards and money that need to be used to make your enemy surrender to your will, then it is precisely these things that should be used. We can see this logic at play in the sphere of policing and counterterrorism, where a mix of methods and means are used to secure political and strategic goals to make enemies succumb to the security state’s will and, if possible, maintain legitimacy in the eyes of the public whilst doing so.

In order to maintain this sense of legitimacy and consent for its power, the security state employs phrases and language that mask the coercion and violence that its practices are rooted in. Terms such as ‘winning hearts and minds’ are used as shorthand to describe a process that entails behavioural change induced through a mixture of manipulative and persuasive acts which seek to pacify and control people. ‘Safeguarding’ is used as a byword for a process that is concerned with pre-emptively intervening in the life of a person who has been surveilled by a public sector worker, such as a school teacher or doctor, and then referred to the authorities on the ground that they are ‘vulnerable’ to becoming a terrorist in the future. The use of these sorts of benign sounding phrases are aimed not only at hiding the physical and mental harms of the security state’s activities. They are also intended to manufacture the consent of the public, including Muslims and communities of colour, and reduce the chances of contestation and resistance to the security state’s activities from emerging. After all, mass resistance becomes more challenging to organise and mobilise if the security state’s violence is about ‘safeguarding’ people and has the buy-in of the very communities who are its targets. The key point is that, because the security state needs to secure the consent of Muslims and communities of colour, there is an opportunity for us to resist its power and contest its desire to act with impunity.

When I was stopped, searched, and questioned on the streets or at airports, I did not consent to what the police did. Yes, I complied with the orders the officers gave but I did not agree with their course of action or their exercise of power over me. Of course, not consenting did not prevent the stop, search, and detentions from being executed. However, it did demonstrate that I was only going along with what the police were doing because there was an underlying threat of further violence being used against me. For example, when I answered the questions put to me under Schedule 7 of the Terrorism Act on my arrival from Spain in 2010, I knew that not answering the police’s questions would most likely lead me to being charged for a terrorism offence akin to ‘obstruction’. To minimise the risk of the police escalating matters, I complied with their orders. The same logic applies to, say, the Prevent programme. When a referral is made to the authorities because somebody is deemed to be a potential future terrorist, their consent is sought before they are formally placed onto the Channel de-radicalisation programme. Often, people may not agree or consent to participating with Channel but will comply because they are fearful that non-compliance may expose them to more intrusive and aggressive forms of police and security state intervention such as surveillance, arrest, and so forth.

The result of consenting and complying to state power, in practice, leads to the same outcome but withdrawing our consent and only complying serves an important symbolic function which can prove unsettling for the security state. This is because simply complying with power indicates that you are only going along with what the police and security agencies order you to do because they have the legal right to use violence against you, not because you agree with their actions, orders, and demands. The withdrawal of consent makes visible how state exercise of power is rooted in fear rather than agreement. Though the state does not require our active consent and can function simply with our compliance, the state craves validation and legitimacy. It seeks to indoctrinate individuals and communities into supporting it but in a gradual and subtle way, so people feel they have arrived at their understanding of the world organically and independently. George Orwell lucidly describes this subtle process of indoctrination as a way of mini- mising resistance in his dystopian novel 1984:

We are not content with negative obedience, nor even with the most abject submission. When finally you surrender to us, it must be of your own free will. We do not destroy the heretic because he resists us: so long as he resists us we never destroy him. We convert him, we capture his inner mind, we reshape him. We burn all evil and all illusion out of him; we bring him over to our side, not in appearance, but genuinely, heart and soul.

No matter how overbearing and powerful the state’s reach may seem, the security state’s need to bring a person ‘over to our side’ in ‘heart and soul’ signals the existence of a space where its power can be questioned, contested, and challenged. By not actively consenting, Muslims and communities of colour can make policies harder to implement by compelling the security state to go it alone. By withdrawing their consent, communities can show that they are only complying with what the security state does because they fear the consequences of non-compliance, not because they support what it does. Though it may not bring power to its knees and force its dismantling, the withdrawing of consent challenges the ideological legitimacy the security state craves. It also serves as a useful avenue for those people who may not be as deeply engaged in resistance to take a stand against power and its coercive and abusive exercise. ‘The duty of the native who has not yet reached maturity in political consciousness’, writes the anti-colonial psychoanalyst Frantz Fanon, ‘is literally to make it so that the slightest gesture has to be torn out of him. This is a very concrete manifestation of non-cooperation, or at least of minimum cooperation.’ Any action that works to make the exercise of power over us more difficult and works to disrupt the impunity with which the security state can work is a step in the right direction, especially for those on the receiving end of policing and counterterrorist violence.