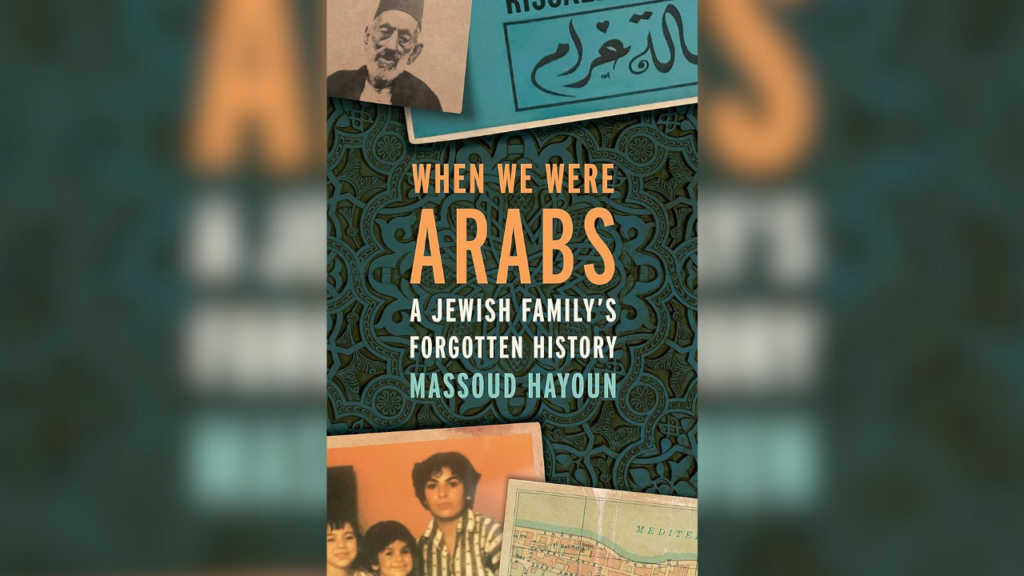

“I am a Jewish Arab. For many, I am a curiosity or a detestable thing. Some say I do not exist, or if I did, I no longer do.” These unapologetic words of reclamation are the opening lines from the decolonial memoir When We Were Arabs: A Jewish Family’s Forgotten History by Arab-American writer and artist Massoud Hayoun, originally published in 2019 by The New Press, with a second edition released in April 2025.

Spanning six chapters and moving between personal memories and geopolitical reckonings, this award-winning work is Hayoun, a former journalist’s attempt to remember the world of his grandparents, which once existed in the Arab world, and reinstate the Jewish-Arab identity they passed down to him. Their family history becomes an anchor to explore larger questions of identity, erasure, homeland, and exile of the Jews of the Arab world.

Hayoun, a third-generation Arab-American born to a single mother, was raised by his maternal grandparents, Oscar and Daida. Oscar was an Egyptian of Moroccan, Amazigh, and Jewish heritage, and Deida was a Jewish woman from Tunisia. Arabic-speaking Jews who migrated to the United States in the 1950s, Hayoun calls them the “last generation to witness Jewish Arabness before exile.”

As he nears death, Oscar asks Hayoun to write down their story—of life in the Arab world and of their exile. After Oscar’s death, and with his notebooks filled with memories of his youth in Egypt, and with Daida’s storytelling, Hayyoun sets out to write his family’s history.

Reclaiming the Jewish Arab Identity

Hayoun’s family is Arab as much as they are Jewish. Arabness is a legacy he inherited from his grandparents. Everything about their life and how they raised him was rich with Arabness. They spoke Arabic, and Oscar was adamant about teaching young Hayoun Arabic. Like every immigrant family, food from the homeland was a holiday ritual. Daida cooked quintessential Arabic dishes, all from scratch, to find a piece of home in their Los Angeles home.

Hayoun’s childhood was steeped in the music and movies of the Arab world, which Daida and Oscar played endlessly. The memoir is rich with references to legendary Arab music and cinema. These evocative recollections of taste, sound, and story are a celebration of the Arabness Hayoun inherited from them.

From the very first chapter, “Origin/Al Usool,” Hayoun is upfront about the political purpose of his writing: “to reclaim the Jewish Arab identity for me and to recuperate it as a stolen asset of the Arab world.” He traverses the complex histories of races and conquests of the Arab world—a site of birth of multiple Abrahamic faiths.

He writes that identity is not merely inherited through blood and religion, but is deeply rooted in cultural inheritance. For him, Arabness is transmitted through language, food, music, humor, and memory. Sunday Arabic lessons, his grandmother’s Arabic food, pan-Arabist songs by Christian Arab singers like Sabah, and bedtime stories filled with nostalgia for their homes in Tunisia and Egypt.

Interwoven with personal histories, When We Were Arabs is a deeply researched work that examines the uprooting of Jewish people from their homelands and the multiple exiles they endured across continents, including from the ‘promised land.’ Analyzing colonial-era policy documents and other historical texts, Hayoun draws out the colonial manipulations that severed the Arabness from the Jewish identity and wreaked havoc across the region. The book, dedicated to “our youth,” seeks to reclaim what colonial powers violently stripped away.

Hayoun exerts, “I am an Arab because that is the legacy I inherit from Daida and Oscar. It is how they remain, for me, immortal. My Arabness is cultural. It is African. My Arabness is Jewish. It is also retaliatory. I am Arab because it is what I and my parents have been told not to be, for generations, to stop us from living in solidarity with other Arabs.”

Hayoun’s grandparents saw themselves as part of the Arab world, not with the dominant Sephardic and Ashkenazi Jews of the US. As a believing Jew, Judaism is spiritual for him, while he claims Arabness is his lived identity. Stressing his lived experience and asserting his Arabness as his larger, primary identity, Hayoun states that he is a Jewish Arab and not an Arab Jew.

This is a distinction he draws from the Moroccan human rights activist Sion Assidon. A Jew himself, Assidon states, “In my opinion, there is a difference between proclaiming oneself an Arab Jew and a Jewish Arab. The first puts the accent on a communal (Jewish) belonging, as superseding belonging to a large group of humanity: the Arabs.”

On Colonial Institutions and the Israeli State

In the chapter titled La Rapture/ The Rupture, Hayoun turns a critical lens on the colonial institutions that had educated his grandparents, shaping their sense of self. Institutions like the Paris-based L’Alliance Israélite Universelle (the Universal Israelite Alliance), founded by French statesman Adolphe Crémieux in 1860 with a “mission civilisatrice” (civilizing mission), sought to promote French language and culture and introduced Zionist nationalism into Jewish communities in the Arab world.

Hayoun’s grandparents’ generation was the first to be educated under the schools operated by such bodies. In one haunting memory, Daida, then a child in a French school run by L’Alliance Israélite Universelle, is told by her teacher that she is not Tunisian but an Israelite—a moment that triggered a lifelong crisis of identity that echoed throughout her life in exile.

The Alliance’s education had repercussions in society. It created a deep generational divide within the Jewish community, leading to strong resistance among Jewish Arab parents. They opposed the Alliance’s agenda, fearing the cultural erasure it implied. Hayoun cites works like Les filles de Mardochée (Mordechai’s Daughter) by Jewish Tunisian writer Annie Goldmann, a novel that captures this generational clash.

Yet, as the political landscape of the Arab world shifted—particularly with the Arab-Israeli wars—Jewish Arabs were caught in the crossfire. Oscar, forced to adopt a pseudonym to conceal his Jewishness in Egypt, faced the increasing impossibility of remaining. Zionist organizations further fueled the fear of pushing migration. Many were airlifted to Israel in the name of salvation.

In the chapter “Darkness/ חושך,” Hayoun explores what happened to those who took that flight, those who left behind their Arab homelands for what they were told was a new beginning. The title, “Darkness,” is profoundly symbolic: it evokes both the literal and figurative descent into obscurity, displacement, and disillusionment.

For Oscar and others, known in Israel as the Mizrahim, life in Israel was nothing like what was promised. Sprayed with DDT upon arrival, interrogated by intelligence, relegated to tents and joblessness, their kids being kidnapped by the state, they faced a myriad of systemic racism from the Eurocentric Zionist establishment.

When We Were Arabs observes and quotes Israel’s founders and leaders like David Ben Gurion and Golda Meir, who saw Jews from Arab lands as inferior and unsuited for the modern state. Ben Gurion, Israel’s founding father and first prime minister spoke of how “the immigrant from North Africa, who looks like a savage, who has never read a book in his life, not even a religious one, and doesn’t even know how to say his prayers, either willingly or unwillingly has behind him a spiritual heritage of thousands of years.”

Golda Meir, another former prime minister with roots in Europe, frequently raised concerns over the migration of Jews from the non-European world. In a visit to Britain in 1964, Meir said: “We in Israel need immigrants from countries with a high standard, because the question of our future social structure is worrying us. We have immigrants from Morocco, Libya, Iran, Egypt, and other countries at a 16th-century level. Shall we be able to elevate these immigrants to a suitable level of civilization?”

These concerns guided her administration in the early 1970s. It favoured emigration from Europe, generously extending them benefits, while withholding them from Jewish Arabs and other non-Europeans.

These sentiments and prejudices of its leaders were projected onto Israeli mainstream society and popular culture. The colonizer’s imagination, as Frantz Fanon wrote, did not spare the Jews who had fled their Arab homes. In its attempt to solve Europe’s “Jewish Question,” Zionism created a new problem: the marginalization of Jews from the Orient. Zionism, Hayoun argues, thus did not liberate all Jews; it racialized them.

With a decent life impossible in Israel, Oscar left his family behind to find work in France. But with the Algerian War for Independence beginning in Algeria in the early 1950s, it became impossible for Oscar to find a job in France with an Arabic surname. Eventually, in 1956, Oscar and Daida migrated again—this time to New York and later settling in Los Angeles, where Hayyoun was born.

Yet even in the U.S., the idea of a universal Jewry failed them. They found nothing much in common with Ashkenazi or Jewish European Americans apart from religion, and both kept their distance, while the Arab communities they encountered were predominantly Muslim or Christian.

Alienated once more, they clung to their memory and culture. Daida cooked Arabic food from scratch; Oscar revisited old stories. They watched and listened to Arabic cinema and music. It was during this period of exile that Oscar made a quiet but radical decision: to give his grandson an Arabic first name—Massoud—at a time when newer generations were increasingly given European or Hebrew names. This act was a deliberate reclamation of the Arabic language and a political statement asserting their unbroken Arabness. Exile had followed them across continents, but so had their resistance, and so had their Arabness.

More Than a Family History

When We Were Arabs is more than a family history—it is a political manifesto, a cultural archive, and an act of literary resistance. Hayoun blurs the lines between memoir and historical scholarship, weaving together personal stories with rigorous critique. Charged with emotional intensity, the rawness of his writing mirrors the fragmentation of diasporic identity. The memoir’s refusal to separate the personal from the political is its greatest strength.

In reclaiming Jewish Arabness, Hayoun disrupts the long-standing Western colonial strategy of conflating Arab identity solely with Islam—a conflation sustained by Orientalist discourse and its institutionalized Islamophobia, both of which have long served to justify geopolitical domination in the Arab world. His narrative defies these reductive frames, reminding the complexity and plurality of Arab identity.

When We Were Arabs thus strongly asserts that the “only way forward” for the Jewish Arab communities is to decolonize from within, especially by the Jewish Arabs of Israel, by rejecting their separation from their larger Arab identity and the legacy of belonging to the Arab world. This call, thus, is a radical gesture of solidarity by contributing to the intellectual and cultural project of decolonizing Palestine.

This memoir also needs to be read as part of the growing genre of Arab diasporic literature. Through expanding the contours of Arab identity, Hayoun’s work not only offers a vital corrective to Zionist historiography but also opens up the possibility of a more inclusive diasporic Arab imaginary—one in which Jews of Arab ancestry can find belonging and voice.

His work invites us to imagine a diasporic Arabness capacious enough to hold multiplicities, and in doing so, unsettles the binaries of Arab versus Jew. For readers unfamiliar with the legacy of Jewish Arabs or the internal hierarchies of Zionism, Hayoun’s memoir offers not just history, but a challenge: to rethink belonging outside the narrow confines of religion, ethnicity, and empire.

Hayoun, a writer and journalist, is now a contemporary painter. With a characteristic bright blue tinted with red, yellow, and green, Hayoun explores the lives and world around him and those already gone. Like his memoir, all his paintings are highly political. Along with intimate and autobiographical expressions, his works also talk about the ongoing war in Palestine, the political repressions in the US, and the many anti-human politics of our times.

In an interview with Contemporary And, he said that his memoir is the starting point for his paintings, and it still influences his work. The lives of his grandparents, the inherited Arabness, and the Arab homeland continue to have a huge influence on his paintings. Along with his forefathers and foremothers painted in blue, often sitting in a club in Cairo or working on the harissa, Hayoun’s paintings are rich with flora and fauna and symbols endemic to North Africa.

“I am part of a generation of North African and Arab creatives recentering our worlds away from Europe and North America, back to the source,” he said. “We will be reckoned with.”

Last month, I sat with Hayoun for an interview to discuss his book and practice. What follows is an edited excerpt of our conversation.

Aysha Sana: You begin your book, When We Were Arabs, by unapologetically stating your identity as a Jewish Arab and also quite powerfully rejecting the dominant narratives about Jewish and Arab identities. You make a clear distinction between ‘Arab Jew’ and ‘Jewish Arab.’ When did you first begin to articulate your multiple identities, and what experiences led to such clarity?

Massoud Hayoun: There was no clear beginning. I was born an Arab person of Jewish faith. I began to care even more when my grandparents, who raised me, died.

AS: The book is critical of Zionism’s racial hierarchies. Your North African Arab family’s story of migrating during the early days of Israel’s formation clearly reflects this. Such discrimination continues even today in the Zionist state. How do you think Jewish Arabs can emancipate themselves?

MH: My focus isn’t so much on Jewish Arab emancipation as it is the ongoing genocide of the Palestinian people. That should be the focus of every person of conscience in the world, Arab or not.

AS: You write about how your grandparents found it difficult to find a community in the US. What has been your experience of forming connections with fellow Arabs in the diaspora as a Jewish Arab? In the growing conflict in the Arab world and among mainstream narratives that not only erase your identity but also pit one against the other, how have you found solidarity and comfort?

MH: I live a solitary life, painting and moving through Los Angeles, silently observing like a ghost. I have no friends. So to answer a question about how fellow diaspora Arabs treat me would be unfair, since I speak to no one, Arab or otherwise. I buy my groceries at an electronic checkout. My human interaction is mainly digital. And the world has gotten a lot darker and colder since 2019, when I published When We Were Arabs.

AS: You wrote in your book, “If there is little discussion of the Palestinian Nakba here, it is in the hope that you will endeavor to hear not me but Palestinians tell it. For too long, that story—of Palestine’s past and future—has been told by non-Palestinians.” Why do you think this is important?

MH: Many anti-Zionists try to speak over Palestinians, who have routinely shown us better than anyone what is happening and how to overcome it. There’s a colonial posturing and condescension in the attempt by shameless self-promoters to use this carnage to draw attention to themselves. That’s not what the paintings or the book are about. There’s a way to stand with and not atop people that I am hopefully modeling with my work.

AS: Food and music from the Arab world are central in your recollections. How did these sensory experiences root you in your Arabness? Could you share any such fond memories of yours?

MH: The fear is frequently that people will think that this book and indeed my Arabness are about food and music and light, little recollections. That would be a mistake. That said, every Saturday, my grandparents would feed me ful medames (fava beans in brine) for breakfast, and we’d watch the hour of Arab American Music Television they’d show on the foreign language channel in Los Angeles.

In the paintings and book, sometimes music and food become touchstones and symbols of deeper-running political ideas. When you paint and write, what you do ceases to be your own; people receive things as they will. For some who miss the point, my work is very nostalgic. I have, for my part, been abundantly clear about the political goals of what I do.

AS: Your book was published in 2019, and with a recent second edition, how have readers, particularly Jewish and non-Jewish Arabs, especially in the diaspora, responded to your work? Have any reactions or conversations particularly surprised or moved you?

MH: Every couple of weeks, I get a nice note saying someone enjoyed some aspect of it. I’ve had a lot of invitations to speak. I reject most of them. I’m saying everything I need to say in the paintings that I haven’t said in the book. But where an organization thinks it would serve the purpose of human liberation for me to stand with them and say again what I’ve said elsewhere, and where I don’t feel myself speaking over silenced people, and where I don’t feel condescended to or tokenized, I’ll speak.

AS: You are also a visual artist. How have your complex identities and the process of writing a highly political memoir influenced your paintings?

MH: I am only a visual artist these days. I don’t believe that the book industry in the United States and the world is for everyday working people. Books here are prohibitively expensive, and there are other obstacles—access to education, time away from work, etc.—that make reading a political theory impossible for people who should have access to knowledge. You only need sight to read a painting. I think a lot more people have connected with my visual work than with the book. Which isn’t to say I’m not thankful for the book doing well; the people—including you—who have enjoyed it brighten my days.

The artwork is an expression of politics and self that, in some way,s emanates from the ideas in the book and goes beyond it.

AS: In another interview, you mentioned that you consider yourself a political artist. What does that mean to you, and why do you think many artists hesitate to acknowledge the political significance of their work?

MH: The United States—and insofar as so much of the world is forced to replicate our culture, the entire world—punishes political partisanship. That is, unless your ostensibly radical ideas still serve an iron-clad status quo. Artists frequently depend on rich, powerful benefactors. Sometimes museums want work that engages critically with what’s wrong in our societies, and that, on occasion, funds genuinely subversive, forward-thinking work.

But you won’t make money to sustain your career unless you paint politically impotent pretty things that people can hang in the lobby of a five-star hotel. It is a privilege to not need to care who buys your work; a privilege I don’t have. But you will never find me painting pretty things that the very wealthy can use to illuminate their lives. Collectors can like or lump what I do; I’ll do it on my terms until the work finds its kindred spirits.

And then some artists use buzzwords like class struggle and colonialism to describe works that couldn’t possibly have any political significance because they want the attention of the industry’s thinkers and intellectual institutions. For them, it seems that there is an enjoyment of the medium and a desire to be taken seriously, but I challenge them to say something soulful and earnest that might stand to affect the direction of the world.

In any case, you’ll never find me painting something that doesn’t have a deeply felt meaning about our human relationship to each other— things that reach into tools obtained in my journalistic work and the privilege of speaking with a great many different kinds of people around the world. Painting is fucking hard, exhausting, and expensive. It is also electric, cutting, and delicious. Every time, every painting, I’m climbing up and over a hurdle. I couldn’t possibly do this if I didn’t feel some sort of thirst for life and dignity welling up within me.

AS: Do you ever dream of living in the Arab world? If so, where would you love to live?

MH: I don’t dream of living anywhere. I think the world is universally horrible these days, and that wherever I live, the challenge would be to find a little pocket of soulfulness and kindness in a willfully soulless, unkind world.

AS: On a lighter note, what do you think is the most “Arab” thing about you?

MH: My blood and soul.