In a village not far from India’s capital, how a Muslim home was razed by state bulldozers

In the village of Nalhar in northern India’s Haryana state, Aas Mohammad, a 58-year-old security guard, had for decades lived in a house he built in 1987 with his own hands. The dwelling, no more than fifteen by fifteen feet, stood as a modest yet solid testament to years of dignified labor. It sheltered his elderly mother, wife, four daughters, and two sons. His father, who passed away in 2009, had also called this place home. However humble, the family had cultivated a life defined by a quiet sense of security and stability. Each morning, Mohammad would leave for the nearby medical college where he worked. Outside the campus gates, his sons ran a tea stall. Through these small earnings the family sustained, even thrived, in relative comfort—until about two years ago.

On July 31, 2023, the Brajmandal Jalabhishek Yatra marched through Nuh, the district that the Nalhar village falls under. The Yatra—an annual Hindu religious procession started in 2020 by the far-right Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) to “revive holy Hindu sites” in the state’s only Muslim-majority district, where the latter constitute more than 79 percent of the population—was allowed despite intelligence reports indicating a high likelihood of violence. The march proceeded, led by members of the VHP and Bajrang Dal, another far-right Hindu organisation, carrying weapons, chanting incendiary slogans.

It was not a celebration of faith—patterns are way past established by now—but a demonstration of Hindu strength, designed to dominate and provoke minority communities, particularly the Muslims. Monu Manesar—a cow vigilante of the Bajrang Dal notorious for his involvement in brutal violence against Muslims and facing charges of kidnapping and murder—had declared he’d be part of the Yatra, too, escalating tensions.

Clashes erupted in various towns and villages across the district after the Yatra was allegedly attacked by a group of local Muslims pelting stones, fact finding reports later suggested. The violence quickly spread to neighboring areas, including Gurugram and Sohna. In Gurugram, one of India’s major business hubs and part of the country’s National Capital Region, a mob attacked the Anjuman Jama Masjid and 19-year-old Mohammad Saad, the mosque’s deputy imam, was killed.

Several other incidents of arson and vandalism were reported in the region. And while Nalhar remained untouched, its Muslim residents were not spared the consequences. The authorities imposed a curfew, suspended internet services, and initiated a district-wide demolition drive against alleged rioters primarily targeting Muslim properties.

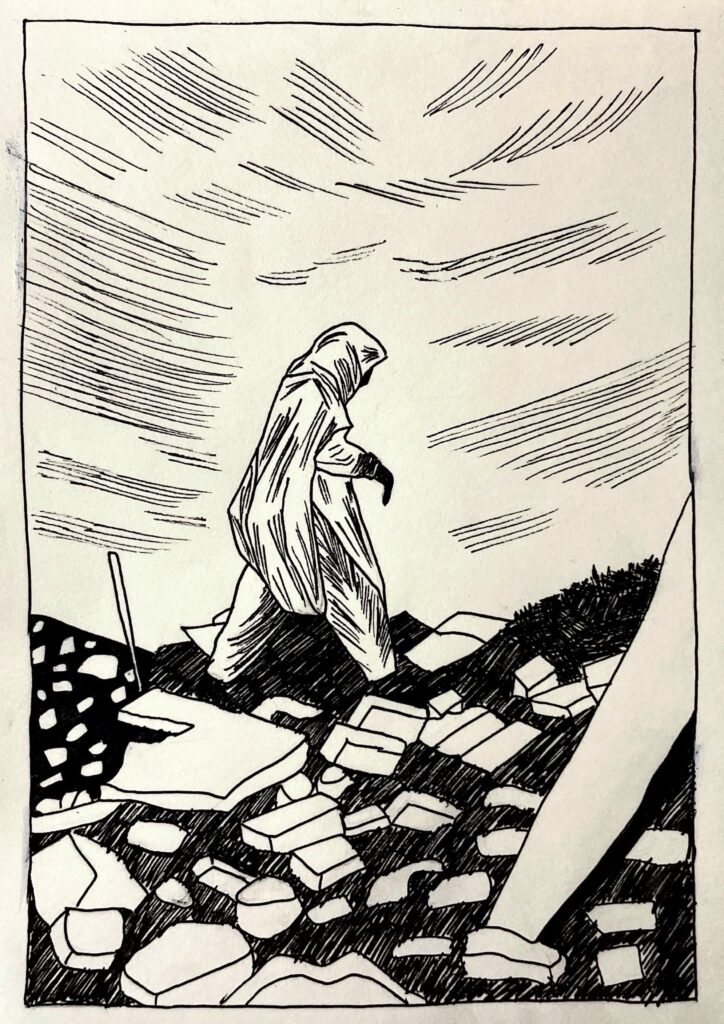

Mohammad was at work on August 4 when he received a phone call from one of his sons. Bulldozers and police had entered the village. By the time he arrived, his home—his only asset and a place of decades of labor and memory—was already being torn apart. The family had received no prior intimation of the government action, bar a piece of paper pasted on the door minutes before the demolition began.

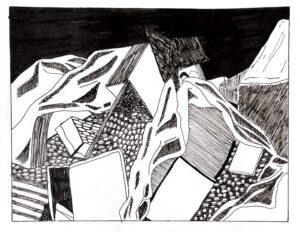

“There was no notice, hearing, or opportunity to challenge or respond to the action,” Mohammad said. Within half an hour, the house was reduced to rubble. Along with the house, the tea stall Mohammad’s sons ran was destroyed, too, and with it much of what helped the family stay afloat—all that the family had built over four decades taken away in the time it would take to brew a cup of tea.

The district administration described the action as part of an anti-encroachment drive aimed at removing “illegal structures,” and alleged the structures were associated with those involved in the violence. The notice against Mohammad, backdated and brought shortly before the demolition, stated that the structure violated building norms and would be removed immediately.

Mohammad’s family, however, had a government-issued electricity connection for over two decades, maintained and paid for throughout this time. Their official documents—ration cards, Aadhaar, and birth certificates—carried the same address. “Kabhi thana tehsil kuch nahi dekha humne,” Mohammad said. “We never had to visit a police station or government office.”

Mohammad’s wasn’t the only family the state left homeless on their own land. In the days following the violence, the government initiated a large-scale demolition drive across Nuh. In five days, over 1,200 homes and commercial structures were razed across 37 sites spanning 71.1 acres, including towns and villages, such as Nalhar, Punhana, Tauru, and Nagina. The overwhelming majority of these belonged to Muslims.

The police claimed that the properties were encroachments on government land or were constructed without proper authorisation and were being used for “anti-social activities.” However, reports indicated many of the demolished structures had valid title deeds and were not built on forest or common land.

Numerous residents across Nuh said the notices were served merely an hour before the demolition commenced, leaving them no time to respond or even to salvage any belongings. (More recent guidelines of the Supreme Court on demolitions requires the owners be served the notice at least 15 days before the demolition.) On August 7, the Punjab and Haryana High Court intervened, too, halting the demolition drive and asking whether what was unfolding in Nuh was “an exercise of ethnic cleansing.”

The High Court also noted the absence of due legal processes including issuing of demolition notices and asked whether properties of a “particular community” were being targeted under the garb of law and order. The court’s intervention was an acknowledgment of the gravity of the violation but for families like Mohammad’s, the damage was done. The court order did not rebuild the shelter they’d lost nor did it return the security of their place in the village. Yet the family’s sufferings were only beginning.

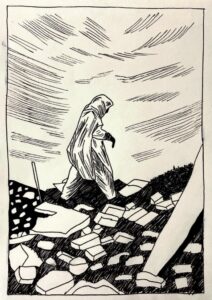

Left in shock, one of Mohammad’s sons had to be hospitalized. The rest of the family took refuge under a tarpaulin sheet set up near the remains of their home—without electricity or drinking water, safety or privacy—the ruins of their life in full view. The family lived in this state for nearly two months. Mohammad was left to pick up the bricks, shattered tiles, and the last pieces of his family’s past.

“What was our fault,” he asked, “that we are Muslims?”

The speed with which the demolitions were carried out in absence of any verification pointed to a familiar pattern, having little to do with law and order and much with a collective punishment of Muslims, a minority now routinely vilified in the public discourse for who they are. Since the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party came to power in India in 2014, the grounds of citizenship for the community have become dramatically unstable, a massive shift attended by intensified marginalization through state policies, targeting in the cultural discourse, and open violence.

Mohammad and his family received no help until the Miles2Smile Foundation, a non-profit relief and educational organization, provided financial assistance to cover their medical costs and basic needs. Months later, the organization raised some more funds and enabled Mohammad to construct a one-room shelter. It was no replacement for the home lost, he said, but at least it meant a roof and some dignity of privacy.

Mohammad was not only devastated by the loss of his home but also deeply disillusioned by the news media. “In person they offered us words of sympathy,” he recalled, “but in their reports they painted us as rioters who deserved to have their homes razed to dust.” The betrayal led him to stop speaking to journalists altogether. In his eyes, and in the eyes of many others who lost their homes, the media did not simply fail to tell the truth—it actively distorted it.

“Sab kuch ghuma phira kar dikhate the,” he said. “They twisted everything.”

Rather than holding power accountable, the media has chosen to amplify the state’s narrative, framing demolitions as a necessary action against alleged criminals, notwithstanding it doesn’t stand the test of law. Over time it has come to normalize this violence by casting suspicion on entire communities while stripping them of their right to be seen as citizens, let alone as victims.

Mohammad’s story, or that of Nuh, therefore, is not an isolated one in India. It is one of many in which Muslims have borne the brunt of “bulldozer justice,” an increasingly normalized form of extrajudicial punishment that skips trials, sidesteps courts, and targets homes rather than individuals, relying not on evidence but spectacle. These demolitions make clear that certain lives are seen as disposable, their claims to citizenship turned precarious, and their right to shelter contingent on political silence. The house that Mohammad built was razed not because of what he did, but because of who he was, where he lived, and how his name sounded.

The destruction also serves a dual purpose: as an act of revenge and a message to others. It warns Muslim communities not to organize, not to speak, not to protest and, most of all, not to exist visibly. Being uninvolved or completely removed from political activity is not enough. Neutrality does not protect people when the state is determined to punish their identity.

The bulldozers that arrived in Nalhar did not come with court orders or legal documents. They came with the backing of political leaders who have repeatedly used the spectacle of demolitions as public displays of authority. They came with cameras, with officials, with no room for any explanation, and above all with impunity.

If the state can demolish homes without notice, without hearings, without evidence, what does due process mean? If punishment can be handed down to entire communities without trial, what remains of democracy? The questions Muhammad raises echo not just across the demolished neighborhoods of Nuh but across all refugee camps in the region and the courtrooms beyond.

But the road to recovery is long and uncertain. The pain of losing his home is not just material suffering. It is emotional, psychological, and generational loss. It has left behind not just broken walls but broken faith, too, leaving him with an acute awareness: when the state turns against you, no amount of honesty or innocence can shield you. His voice, though weary, still demands an answer.