In a move raising serious concerns about freedom of speech, the Indian State in Kashmir has formally banned 25 books under its new criminal codes. The order, issued on August 5 without due process or judicial hearing, declares that these books “propagate false narratives and secessionism” and must be forfeited to the government. The order of forfeiture makes it a crime to possess copies of the book and any associated documents and circulate them. It was issued on August 5, 2025, six years after the Indian government revoked Jammu and Kashmir’s constitutional autonomy under Article 370 in a controversial move, without following due process, consent, or judicial review.

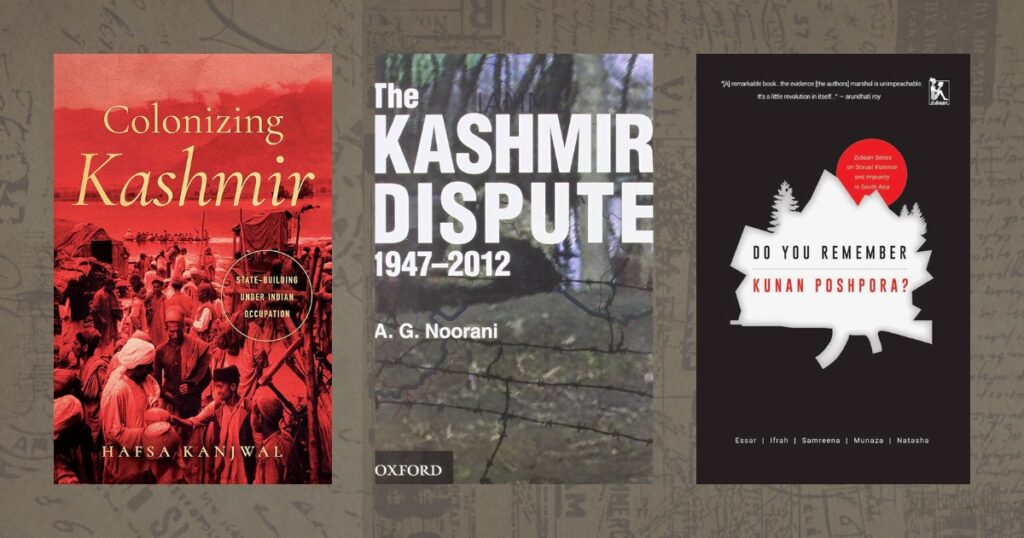

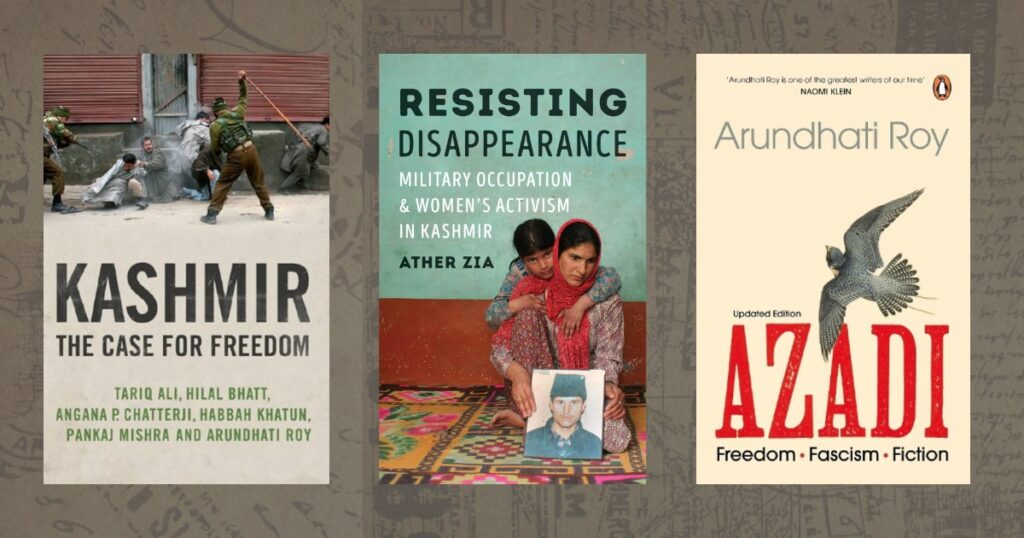

Some of the authors whose works have now been banned include Hafsa Kanjwal, whose Colonizing Kashmir examines the mechanics of Indian state-building in the region; Abdul Jabbar Gockhami, author of Kashmir Politics and Plebiscite; and Essar Batool (and others), whose Do You Remember Kunan Poshpora? documents the suppressed history of mass sexual violence by Indian forces. The list also includes Resisting Occupation in Kashmir, a collaborative volume by Haley Duschinski, Mona Bhan, Ather Zia, and Cynthia Mahmood, and Resisting Disappearance, Ather Zia’s searing work on women’s lives under military occupation. Other books include feminist scholar Seema Kazi’s Between Democracy and Nation, Victoria Schofield’s Kashmir in Conflict, and A. G. Noorani’s authoritative The Kashmir Dispute. Anuradha Bhasin’s A Dismantled State, Radhika Gupta’s Freedom in Captivity, and works by Arundhati Roy and Ayesha Jalal also appear on the list, marking a sweeping crackdown on scholarship, journalism, and political memory.

Days after the ban, police in Anantnag raided local bookshops to enforce the order, combing through shelves, seizing titles, and threatening legal action against anyone found in possession of the proscribed works. A senior officer confirmed the raids, stating that bookstore owners had been warned and that “violators will face legal consequences.”

Historian Hafsa Kanjwal, whose Colonizing Kashmir is among the banned texts, frames the order as part of a wider campaign of narrative control.“The book ban shows the extent to which the Indian government seeks to control information and knowledge production on Kashmir. It is important to see it in a broader and historical context one of many attempts to erase a narrative that challenges the Indian government’s propaganda about Kashmir.”

The books were proscribed under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) and the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS)–the new criminal codes that replace the colonial-era Indian Penal Code (IPC) and the Code of Criminal Procedure 1973 (CrPC), respectively. Invoking Section 98 of the BNSS, which is modeled after the old Section 95 of the CrPC, the state can seize publications it deems “objectionable” without trial, judicial process, justification, or accountability.

Anuradha Bhasin, editor and author of A Dismantled State, whose work is now banned, described the order as the product of a larger regime of fear. “This is quite bizarre, picking 25 books that seem randomly selected… Most are about history, politics, or human rights in the borderlands,” she said. “This government wants to control the narrative and silence any voice critical of the state. It’s straight out of a fascist playbook; it reminds one of the Nazis.” For Bhasin, the timing is telling. “In Kashmir, the government does this every now and then to induce a new level of fear. They need to remind people who’s the boss.”

Author and poet Ather Zia, whose works Resisting Disappearance and Resisting Occupation in Kashmir appear on the banned list, condemned the move as a sweeping assault on critical thought. “The Indian government has not only banned a host of books on Kashmir, including mine, but has invoked powers that allow any police officer to seize them anywhere in the country,” she said. “A magistrate may even authorize a police officer to search homes and premises where a copy is found or suspected.” Reflecting on the broader implications of this crackdown, Zia added, “In the digital age, such measures are not only moot, they expose the fear of ideas.” And asked, “How can a book become a singular threat to any legitimate authority?”

When the law is wielded like a blunt instrument of censorship, it doesn’t just silence — it maims. In its wake, what emerges is an ideological infrastructure: a state-sanctioned machinery built to erase scholarship, criminalize memory, and claim total monopoly over the narrative.

Control the Story, Own the State

The Indian State has long obsessed over controlling how Kashmir is spoken of, not just in headlines, but in footnotes, textbooks, archives, and memory itself, investing extraordinary effort in perfecting the machinery of censorship across the valley. After the revocation of Article 370 in August 2019, the Indian State moved swiftly to criminalise any form of dissent, but also the very documentation of history. Two kinds of people were immediately targeted. First, journalists are those who chronicle daily life under occupation. From Sajad Gul to Fahad Shah, the arrests have been relentless and punitive. Second: human rights defenders like Khurram Parvez, imprisoned for recording the disappeared, the tortured, and the silenced.

I have previously written about how the Indian State is silencing journalists in Kashmir and killing off the remnants of Kashmir’s Free Press. I documented how journalists have been summoned, interrogated for hours, and had their houses raided in counterinsurgency-style operations. Since 2019, many Kashmiris have been put on a no-fly list, and others have had their passports taken away. In 2022, India stopped Kashmiri photographer Sanna Irshad Mattoo from travelling to receive the Pulitzer Prize, which she received for her work with Reuters covering Covid-19’s toll on India. In July 2023, it was reported that journalists in Kashmir writing for international publications received e-mails from Indian authorities “to surrender their passports for being a security threat to India, or face action.” Another journalist told me, “They want journalists to be copywriters producing ads for this occupation.”

Ideas as Contraband

When Delhi University professor G.N. Saibaba was arrested and sentenced under the stringent anti-terror law UAPA, one of the accusations against him was based on the books found in his possession. The prosecution’s evidence of a literature professor “waging war” against the mighty Indian State consisted of letters, newspapers, umbrellas, pamphlets, books on Marxism, and videos seized during searches, whose legality the defence repeatedly challenged.

For the Indian Justice system, books, pamphlets, BBC documentaries, and video recordings were sufficient to suggest that Saibaba and others were guilty of waging war against the Indian State.

The police seized his bookshelf as evidence of sedition, the Indian court upheld the logic, and the prison swallowed his body. Justice M.R. Shah, one of the two bench members in the trial, recorded an oral remark during the hearing, arguing that “the brain is more dangerous” than any action. When an Indian justice declares that the mind itself is a threat, the implication is unambiguous: thought becomes the terrain of state control.

What the Indian State implements in the mainland, it replicates in the valley with greater precision and far more violence.

What the Indian State seeks to forfeit in Kashmir is not just books, but the very capacity to imagine otherwise. This is censorship, but it is also subpoenaing memory, disciplining imagination, and erasing lived experience. The project is larger than just banning texts; it is about extinguishing the possibility that other worlds ever existed or could be dreamed again. As Hafsa Kanjwal points out, “Of course, what settler-colonial states like India do not seem to understand is that books can be banned, but people’s desire to know and learn about their condition cannot be. Already, many Kashmiris and others are using the list as a sort of introductory reading list on Kashmir. What the government has basically done is elevate the profile and visibility of these books.”

The Law as Ideology

What makes the current order even more disturbing is that it emerges from new criminal laws that were marketed as “decolonial,” a rejection of British-era repression. In reality, the BNS and BNSS intensify authoritarian power and replace British censorship with aggressive Hindu/ Hindutva sovereignty.

For instance, the order uses “false narrative”, a vague term, as justification for turning the states’ unsubstantiated opinions into offence.“False narrative” is not a legal category; it is an ideological accusation and a way for the state to designate certain histories as unthinkable, and certain lived realities as illegal. This transformation of language in the service of repression is not accidental. It allows the government to redefine dissent as treason and scholarship as sedition.

The annexure to the order, the list of banned books, has now been made public. In effect, it functions as a public blacklist. It sends a message: these are the texts that will get you in trouble. Publishers, libraries, scholars, and bookstores take note. This is both censorship and deterrence, a warning shot aimed at knowledge itself.

“It’s not about books. It’s about fear,” said Bhasin. “They want to remind people who’s the boss. To induce panic, to raise a generation with no information, no memory. That’s the politics of erasure.”

A Pattern of Disappearance

What is unfolding in Kashmir is a systematic campaign of epistemic violence—the deliberate dismantling of how a people remember, know, and imagine. The recent book ban is only the latest act in a broader architecture of erasure. School curricula have been stripped of Kashmir’s political history, hollowed out to serve a state-authored fiction. Independent media outlets have been shuttered or criminalised, their voices drowned in accusations of sedition. Archives and oral history projects are surveilled, censored, or made to vanish quietly. Artists, researchers, and public intellectuals are hounded, interrogated, imprisoned, or pushed into exile. This is a project of disappearance, not only of individuals but of entire histories, languages, and futures. Bhasin sees the move as designed to erase generational knowledge and stoke fear: “They want to ensure the next generation has no knowledge, no information. To raise non-thinking people.”

The land is being reshaped through settler-colonial laws, the body is monitored and punished, the mind rendered suspect, and memory itself targeted for deletion. The goal is not merely to control what is said or written about Kashmir—it is to seize total dominion over how Kashmiris live, think, remember, and dream. As Ather Zia articulates, “It’s a dark reminder, symbolic of incessant imperial hegemony over Kashmiri land, bodies and minds.”