January 1st, Kharsawan Golikaand: A Day of Mourning, Resistance, and Celebration For the Adivasis of Singhbhum

“Was there any need for bad blood, for bitterness, between Orissa, Bihar, and the Central Provinces?” asked Jaipal Singh Munda, Adivasi leader and Member of Parliament, during his Presidential address at the ‘All India Adivasi Mahasabha’ held in Ranchi on 28th February 1948. The “bad blood” and bitterness he was referring to stemmed from the Kharsawan Massacre, locally remembered as the Kharsawan Golikaand.

The Kharsawan Golikaand refers to the brutal massacre of thousands of Adivasis on 1st January 1948, during the weekly haat (market) in Kharsawan, Jharkhand. In the wake of India’s independence in 1947, conflicts and tensions had already erupted between Bihar and Orissa over the control of the mineral-rich regions of Seraikela and Kharsawan. Against this backdrop, on 18 December that year, the Seraikela-Kharsawan region was integrated into Orissa, a decision made without the consent of its Adivasi population, which inhabited the area.

For the Adivasis of Seraikella and Kharsawan, this was more than an administrative change. It was a direct affront to their longstanding struggle for self-determination—a demand articulated through the Jharkhand Movement, the oldest autonomy movement in post-independent India. The merger was seen as a betrayal of their aspirations for a separate Adivasi homeland, rooted in their unique cultural, political, and historical identity.

In response to the integration, thousands of Adivasis assembled peacefully at the Kharsawan haat to protest the merger and assert their rights. Anticipating this act of resistance, the Orissa administration deployed armed police forces to the site. Without warning or provocation, the police opened fire on the unarmed crowd, transforming a peaceful protest into a massacre. As Jaipal Singh Munda notes, the killings were not accidental. They were a calculated attempt to deliver a rude shock to the Adivasi Movement.

This year, alongside two of my friends, Babulal Goipai (whom I call Babuda) and Pushpa Murmu, we made our way from Jamshedpur to Kharsawan. 77 years later, a quarter into the millennium, the site of the massacre has become a political pilgrimage site for the Adivasi community. A pilgrimage that encompasses a gathering of collective mourning, celebration, and perseverance, and a continued struggle against systemic violence and erasure.

Arriving at Kharsawan

The road on the way to Kharsawan felt eerily familiar. A political pilgrimage site with posters and banners all along the way, up to the sites of various political parties. All of them, trying to appropriate the massacre without addressing the larger problems—like denial and destruction of natural resources, land alienation, loss of traditional value systems and cooperation, alcoholism, violence, migration, diseases and ill-health, unemployment, scavenging for survival, and environmental pollution that are the stark reality of Adivasis living in Jharkhand today.

The lack of accountability and the deliberate erasure of physical evidence—like the trees and houses with bullet holes surrounding the Kharsawan Golikaand—have made it easier for political parties to appropriate and commodify Adivasi grief. Each year, leaders from across the political spectrum make their perfunctory visits, arriving briefly, offering rehearsed condolences, and leaving just as quickly, with little engagement or acknowledgment of the deeper historical and emotional weight carried by the community. At every junction on the road to Kharsawan, the banners and posters were also accompanied by police and military officers stationed to keep constant surveillance, their presence more intimidating than protective.

As we arrived at Kharsawan, the sheer scale of the gathering was impossible to ignore. The roads, once quiet, were now crowded with Adivasis from Jharkhand and also other neighbouring states, including West Bengal, Odisha, Assam, and Bihar. Men and women were dressed in traditional attire—saris with green or red borders for the women, dhotis for the men, their clothes marked by distinct Adivasi patterns.

A few hundred meters away from the memorial, Babuda, Pushpa, and I joined the ‘Adi Sanskriti Evam Vigyan Sansthan’, an organization dedicated to the scientific, cultural, and linguistic welfare of the Ho Adivasi community, for entry into the memorial site. I watched and marched along as the deuri, the village priest of Adma Gaam in Kharsawan, followed by his wife and the rest of the group, all carrying symbolic objects in hand for offering at the memorial.

We marched towards the memorial, contributing to the growing cacophony of mourning and protest. Every group was vociferously sloganeering in harmony in the Ho language.

“Beer Boyor Ko” [All Brave Martyrs]

“Jorong Jid, Jorong Jid” [Long Live, Long Live]

“Beer Poto Ho” [Brave Poto Ho]

“Jorong Jid” [Long Live]

“Beer Birsa Munda” [Brave Birsa Munda]

“Jorong Jid” [Long Live]

“Kharsawan Re Dane Yan Ko” [All the Martyrs of Kharsawan]

“Jorong Jid” [Long Live]

[Translated by Babulal Goipai]

By now, the site had transformed into a protest, charged with an air of solidarity and exhilaration. We moved with the rally, protesting and remembering the brave martyrs like Birsa Munda, who led the resistance against dual oppression from feudal landlords (diku) and the colonial administration. This act of remembrance honors them as human beings who lost their lives at the hands of the state, resisting the appropriation of Adivasi leaders as Bhagwan or gods, which renders them supernatural and distances them from their political legacy.

The Sacred Act of Remembering and Mourning

Apart from a few written accounts that briefly mention the incident and the presidential speech delivered by Jaipal Singh Munda—archived in the book Jharkhand Movement—most of the cruelty and violence that took place at Kharsawan continues to live on only through oral history.

At Kharsawan, just a few meters from the memorial site, I sat with Baburam Soy from Jhinkpani and Bandhu Bankira from Jojodih. Under the sharp winter sun, they recounted how the Orissa government had unleashed a hail of bullets on Adivasis for nearly 30 minutes, who had peacefully gathered at the “Kharsawan Guruvar Haat”. They spoke of the mango trees that once stood in the marketplace, bearing the scars of bullet wounds.

The state has done little to acknowledge, let alone preserve, the truth of what happened. Through collective remembrance and the retelling of the massacre, through songs, testimonies, and gatherings at the site, the Adivasis are resisting the state-sponsored erasure of a brutal event that shattered families, claimed countless lives, and left a deep wound in the community’s history.

Baburam Soy recounted how the bodies of those killed were dumped in nearby wells and forests, left to decay without dignity or mourning. He and Bandhu ji spoke in a mix of Hindi and Ho, a language I could not fully grasp. As their voices rose and fell, sharing the harrowing details, I felt an intense sense of loss, not just for the lives taken that day, but for my inability to fully connect with the language, the cultural depth, and the immense pain their words carried.

Ritualistic Offering at the Memorial—Diri Dulsunum

At the memorial, various groups of people gathered to mourn and pay their respects in ways that reflect their community rituals. The Adi Sanskriti Evam Vigyan Sansthan conducted the Diri Dulsunum, which translates to “putting oil on stone”. The diri, the megalithic stones of the Ho Adivasi community, are markers of a person, a community, a place, and/or an event (in this case, of the Kharsawan Golikaand).

They are repositories in the most abstract solid form that connect the community to the land and their histories. The funerary stone monuments known as sasandiri in the Ho language serve as physical evidence of genealogies and thus function as mnemonic devices, with their sites acting as spaces of commemoration. The Diri Dulsunsum usually takes place at a family level. However, at the Kharsawan Golikaand Shaheed Sthal (Martyr’s Site), the Diri Dulsunum takes place at the monumental stone to commemorate the massacre and pay tribute to the martyrs. The grief is remembered and felt again.

As they gathered around the samadhi sthal, the sound of grief echoed through the air as men and women, their faces etched with sorrow, wiped away tears while the dulsunum was taking place. After chanting prayers in the Ho language, collective mourning took place. Everyone gathered around the memorial started bawling. I remembered Baburam ji’s words. “We do Dulsunum not just because it’s a ritual,” he said. “It is a way to remember, to purify. The martyr’s spirit is remembered by offering mustard oil. We will never forget.” It is this act of remembering, this refusal to let the state’s violence fade into the past, that defines the spirit of Kharsawan Massacre Memory Day.

I stood still, recording this moment on my phone, but soon realized I was no longer just a witness, I was part of the mourning. The collective grief of the Adivasis, the weight of generations of loss and injustice, was palpable. One by one, mourners placed a few drops of mustard oil on the symbolic memorial grave and moved to the next site.

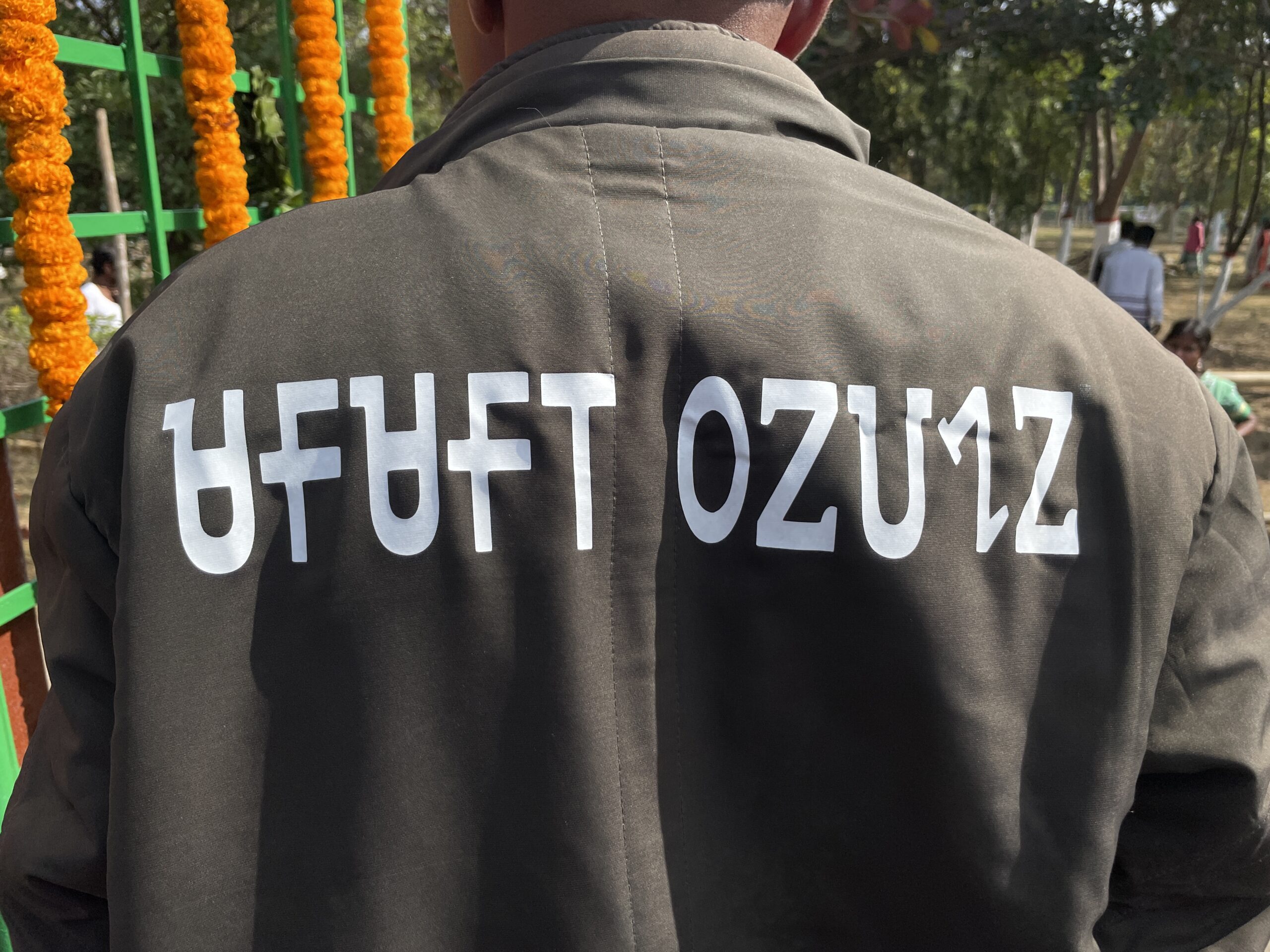

After offering our tribute, we followed the procession to the bid-diri, a large upright memorial stone inscribed with the Ho script Warang-Chiti, with the translation in Hindi. The Dulsunum ceremony was repeated here, and again, tears fell as people remembered. There was no rush, no impatience. The processions continued slowly, as each person engaged in the sacred act of remembering and mourning.

For Adivasi communities, the act of remembering is not merely personal—it is deeply political. In a time when saffronization seeks to fold Indigenous communities into the Hindu religious order, erasing their distinct histories, cosmologies, and political struggles, rituals like Diri Dulsunum assert an autonomous Adivasi identity. They resist the homogenising narratives that attempt to absorb Indigenous spiritualities into the mainstream fold.

In this context, mourning becomes defiance; remembrance becomes resistance. Through these rituals, the community not only grieves but also reclaims its history, language, and future on its own terms, refusing to be subsumed by a state and society eager to forget or rewrite their truth.

Resistance and Celebration Outside Shaheed Sthal

The mood outside the Shaheed Sthal was different—a mixture of reverence and solidarity. The Adivasis do not just gather to mourn; they gather to resist and to celebrate. After the dulsunum, Babuda and Pushpa left while I lingered around with some friends in the local village market outside the memorial. The village haat/markets of the Adivasis are an integral part of their social, cultural, and economic ethos.

On the memorial day, the market and stalls teemed with Adivasi literature and cultural objects. It was alive with vibrant stalls displaying handmade Indigenous instruments, traditional outfits, intricately crafted bows and arrows, and posters of Adivasi leaders and reformers—Tilka Majhi, Birsa Munda, Poto Ho, Sidhu and Kanhu, among many others. It was more than just a space of commerce; it was a space of assertion, memory, and cultural continuity.

There was literature in Adivasi languages such as Santhali and Ho language that isn’t part of any mainstream literature festival. While the Shaheed Sthal on 1st January became a space of mourning, remembrance, and memorialization, the marketplace outside existed as a social space for meeting and greeting.

As Dr. Bodhi S.R. remarked in his presentation “Decolonising Research Methods: Towards a Dialogical Historiography” at an Oral History workshop, “Adivasis are on their way to modernity through adaptation, negotiation, and freedom.” The marketplace reflected exactly that—an evolving yet rooted expression of Adivasi life. It was a living archive of Adivasi ways of knowing and being, where objects and artifacts embodied the spirit of the gathering. It carried forward the memory of resistance and the continuity of culture, echoing the resilience of a people who have never stopped adapting, creating, and asserting their presence on their own terms.

The Larger Significance of Remembering Kharsawan

The Adivasis have long countered the official state narrative by constructing their own ways of remembering and commemorating their past. They are active forms of resistance against the ongoing historical erasure of Adivasi identity, agency, and lived experiences.

At the Kharsawan Golikaand Memorial, on New Year’s Day, the site transforms into a powerful confluence of mourning, protest, and celebration. Thousands of Adivasis gather not only to grieve the loss of those brutally killed in 1948, but also to assert their continued presence, their refusal to forget, and their right to historical memory. The space becomes charged with songs, speeches, rituals, and tears—a living embodiment of what the state has sought to suppress.

The Kharsawan Golikaand is not merely a regional tragedy; it is a fragment of a much larger map of state-sponsored violence against Adivasis. From Koel Karo to Narayanpatna, from Pathalgadi to Deocha-Pachami, the state’s developmental violence continues to target Indigenous bodies and territories.

Yet, the Adivasi struggle for jal, jangal, jameen (water, jungle, land) is far from over. It lives on through the collective gatherings that reject forgetfulness, and through the quiet but powerful act of returning to the site, to the memory, to the fight.