When serious ethical breaches go unchecked by those in positions of responsibility, and when the powerful refuse to speak up or fail to uphold accountability, they create a political economy of silence. You can read part two of the essay here.

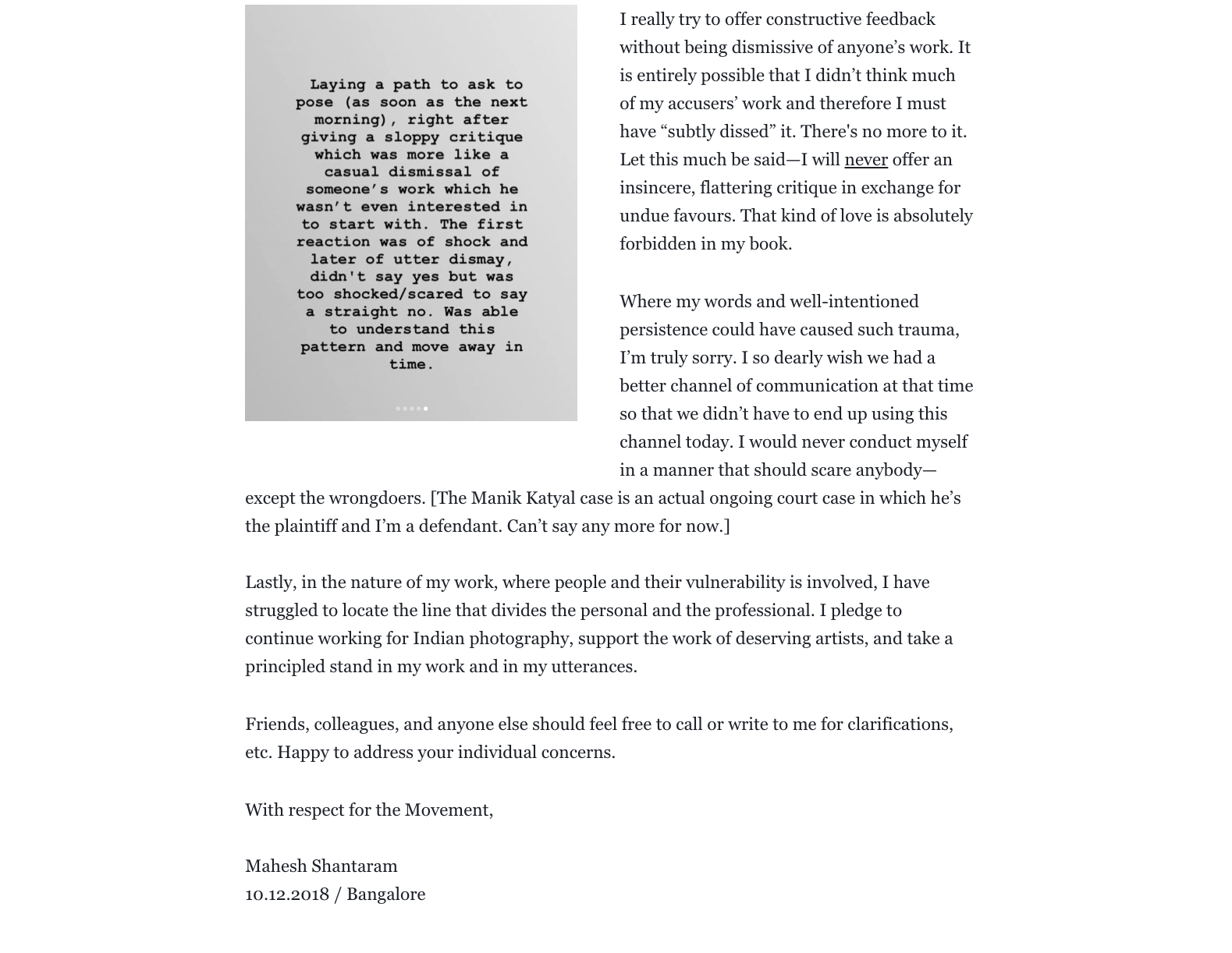

On 8 and 9 December 2018, Instagram account Scene and Herd posted two anonymous allegations of sexual harassment by a “well-known wedding/art photographer from Bangalore” (see here and here). Less than 24 hours after the allegations were posted, Bangalore-based wedding photographer Mahesh Shantaram came forward identifying himself as the photographer and responded to the allegations in a Facebook post.

Scene and Herd was created in the aftermath of India’s #MeToo movement with an aim to “[cut] through bs [bullshit] in the Indian art world, one predator and power play at a time.” They have been publishing accounts of sexual harassment, misconduct, and sexual assault allegations in the Indian art and photography world since October 2018. They continue to publish various accounts anonymously, enabling survivors to come forward without the fear of reprisals. All survivor accounts are anonymous, but some directly identify the perpetrators. Last year, the account published allegations against several powerful artists like Subodh Gupta, Jatin Das, and Riyas Komu, also the co-founder of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, as well as Sotheby’s India MD Gaurav Bhatia.

Since lawyer Raya Sarkar’s LoSHA (List of Sexual Harassers in Academia) was published in 2017, there has been a deluge of young women in India across academia, journalism, film, and art that have shared their accounts on various social media platforms. Artist, photographer and curator Vidisha Saini says that anonymous accounts became necessary because people taking a stand were being sidelined and denied opportunities for being “too much” or “too political.” She states, “It is important to dismantle the system, and anonymous accounts like Scene and Herd have helped achieve that.” In a culture that penalizes those who take a stand, anonymity has become essential to break the silence around sexual harassment and assault and protect those who support the survivors. Another Delhi-based artist, who spoke under the condition of anonymity said, “Publicly they are dismissing Scene and Herd, or feigning indifference. Behind closed doors, you can see the fear… No one is really surprised by the allegations or the names that have appeared.”

While many of women that have spoken out on these anonymous forums have found solidarity, very few of the men have faced any real consequences. Gatekeepers, including women, have remained silent and continue to enable many of the perpetrators. While the culture of silence is being breached one story at a time, the culture of fear, shame and turning survivor accounts into voyeuristic salacious gossip has remained. Spiteful reactionary attacks and bullying survivors on social media and other spaces have allowed men to hide behind a wall of silence and collusion.

So it was rather unusual to see a male photographer, reacting to an anonymous statement, step forward to not only claim that he was the man in question but do it in a publicly accessible platform like Facebook. It isn’t every day that a man accused of sexual harassment and predatory behaviour offers an unsolicited mea culpa, especially one who had not even been named by the accuser.

Using a language civilised, inclusive, confessional, and apologetic, Shantaram’s public post was well received. Within hours, a number of his friends and fellow photographers congratulated him for his “bravery” and “courage.” Someone even called him a “hero.” One of the respondents, a photographer, gave Shantaram a “clean chit” and claimed “it is a dangerous time for men.”

Other men used the post to discredit Scene and Herd and absolve themselves of allegations against them. Many, including women, offered him their support and encouragement. Others took to belittling the women who had made the allegations.

Many of these photographers defended Shantaram’s practice arguing that “one has to be persistent to get stories and access,” “no one was going to offer access in a platter, so this was ok,” and “you are annoyingly persistent and I love you for it.”

Over the next day, I saw Shantaram’s Facebook post become a toxic space. The responses to his post propagated the worst kind of stereotypes about women, a display of how misogyny and toxic masculinity work to silence dissent and collectively shame women. And at no point did Shantaram intervene to address the way his post was quickly deteriorating into a free-for-all about the “unreasonableness” of women and the “mendacity” of their intentions. When they were in support of him, regardless of the misogyny and violence they spewed, he remained quiet. When they were critical of his posture and challenged him, as I did, he responded by being dismissive and patronizing: “I find your ideas interesting,” “I know you mean well,” and “Shall we leave it at this?”

On 12 December, the Mumbai-based Indian newspaper Mid-Day published “Notes from an apology” stating that Shantaram can “give tutorials on how to write an apology.” It underplayed and mischaracterized the women’s allegations—“who didn’t like how he approached them to pose for his work”—and went on to quote Shantaram at length, without citing the women. It was glaring abuse of power and position, a deep structural inequality where a man could claim innocence in public and receive accolades for his apology-writing skills while the women could be violently erased and their allegations swept under the camaraderie of bro-hood. It was also interesting to note how Shantaram’s confession and the women’s allegations are differentially received by the public.

For instance, isn’t it strange that practically no one argued that Shantaram was lying, or that he was simply trying to gain attention, or that he was misreading the situation, claims that were and are easily made about the womens’ statements? He is assigned credibility, civility, and the benefit of doubt while the women are classified as threatening and assigned fear, shame, and suspicion as default positions.

It was both unacceptable and unethical. I wrote to Mid-Day editor-in-chief Tinaz Nooshian on 16 December 2018 citing these concerns, asking the newspaper to retract the piece. To date, Nooshian has not responded. Similarly, many institutions that have supported Shantaram’s work—like Tasveer, Alkazi, or his own agency, VU—have remained silent and made no public statements.

There is a pattern to his obfuscation.

Yes, I was wrong. My idea bombed.

Oh, wait! I am still right, and I will march ahead.

There’s a thread that connects this rhetoric. It is smug, self-indulgent, and inconsiderate.

AUTOPSY OF AN APOLOGY

Since #MeToo, men around the world have performed apologies to redeem themselves and begin the return to their social worlds. All these apologies have one thing in common: they are non-apologies, centred on the lives, careers, and ambitions of the men. Their behaviour from the spectrum of harassment to assault is crafted as an anomaly, a mistake that can be redeemed. The survivors become an appendage, an afterthought. There is no place for us to think about the women, or how we can begin the process of some kind of restorative justice.

How is it possible, I wonder, that men like Shantaram can speak in public, unashamed, unapologetic, unabashed, in a way that few, if any, were willing to challenge him? How are discourses employed, tactics chosen, obfuscations offered, and language used to shift the burden of proof, fear, and shame on to the victims? How do we begin to critique a culture that upholds misogyny and the conduits that facilitate this behaviour? Shantaram is simply a means to critique the toxic wasteland of prejudice and privilege and the photography/art world’s remarkable capacity to conform and stay silent that makes this culture possible.

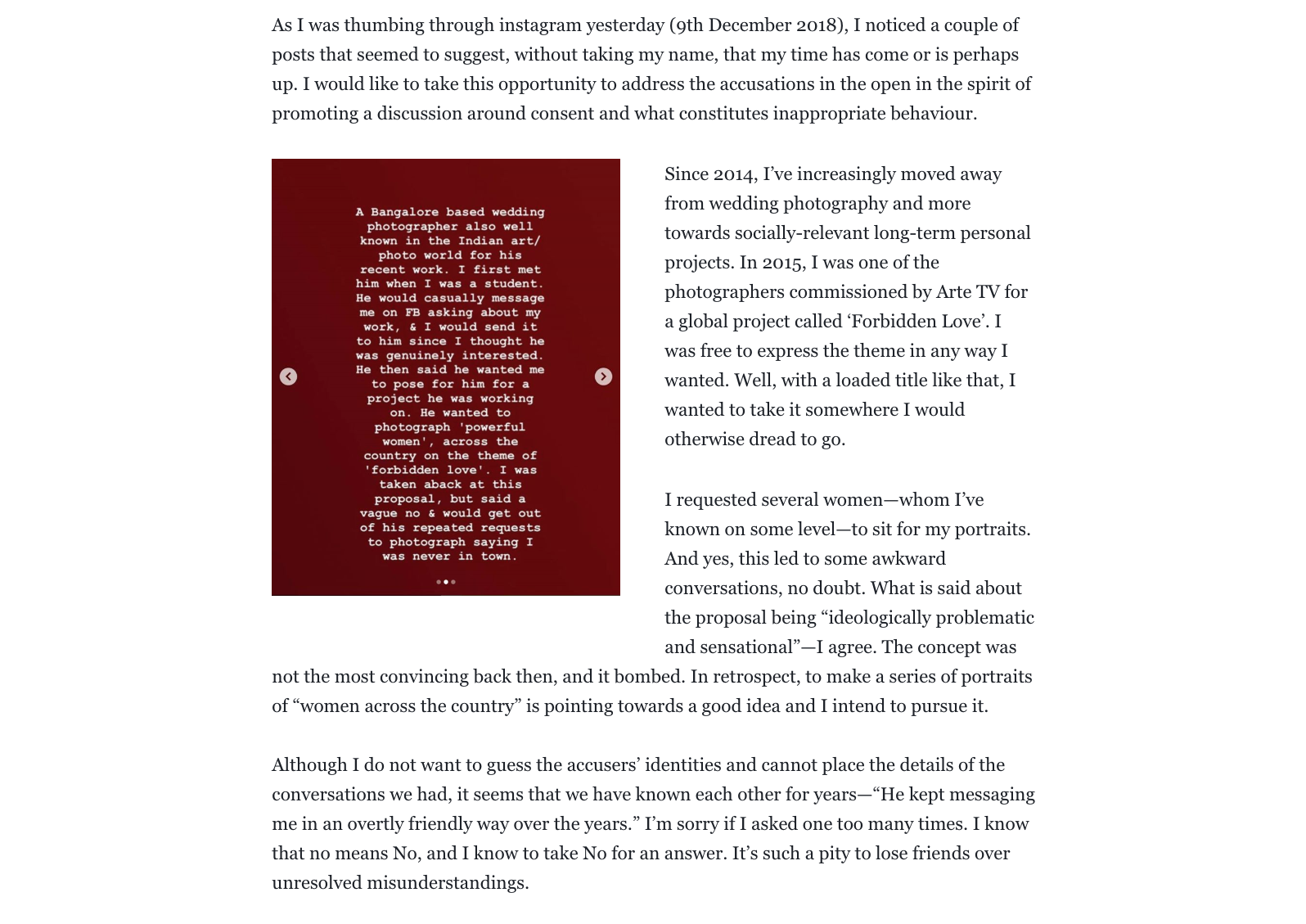

Shantaram claims that he stepped forward because he wanted to “address the accusations in the open in the spirit of promoting a discussion around consent and what constitutes inappropriate behaviour.” And yet his response was a systematic exercise in silencing and discrediting his accusers. Instead of hurling direct insults at the women, or denying the incident, he hurled liberal bromides, feminist warrior defences, obfuscatory language, and deflecting phrases. But, no real apology. How did he do it?

One: The woke man

Shantaram begins his Facebook post by vehemently declaring his liberal, feminist credentials. Even Shantaram’s Instagram page carries the slogan “Fuck Patriarchy,” although it isn’t quite clear how he intends or proposes to do that given that his career is largely based on the photographing of that most patriarchal of social institutions, the heterosexual marriage. He insists that he has “been a vocal upholder of feminist causes and a fighter of the good fight” but no evidence of this claim is offered or available for us to see. He goes on to argue, “I know that no means No, and I know to take No for an answer,” echoing the now popular “no means no” slogan associated with anti-rape movements.

So why does he begin here? He wants the reader to know that he is a man who is incapable of doing what the women have accused him of doing. These assertions of feminist warrior-hood and of knowing when no means no assume that those who fight the feminist fight cannot be sexual harassers or those who stand with feminists cannot be abusers or those who “fight the good fight” cannot be predators.

These self-celebrated “credentials” become Shantaram’s pedestal to acquit himself. Fix the blows and visible cracks to his well-cultivated public persona, and he can then begin the next phase of his disavowals and dismissals. His liberal feminist declarations are a denial, a rejection, an unequivocal claim that the women are lying because someone with his liberal “credentials” would never “intentionally” indulge in sexual harassment or make unwelcome and unwanted overtures or indulge in predatory behaviour.

As Emily Reynolds talking about Louis CK argued: “Simply calling yourself a supporter of women does not mean you are one. Being nice doesn’t mean you can’t also be abusive; neither does calling yourself a feminist or declaring men dangerous. Believing that a man expressing feminist sentiment—or being your friend, or seeming like a nice guy, or “never doing anything to you”—means he can’t be abusive does a disservice to the complexity of abuse: the two things are simply not related.”

I wonder what form of feminist liberation he was pursuing when he interpreted a project called “Forbidden Love” to mean sexually objectifying and disrobing women in front of his camera. What sort of “good fight” was he engaged in when he repeatedly messages this young woman not in professional but in a clearly personal capacity so much that she had to remove him from his social media accounts? He publicly claims that he knows when no means no, but in reality he pursued at least one woman in overtly inappropriate and personal ways over the course of some years for what had nothing to do with his projects or his professional interests.

There is a lot of noise and appropriation of progressive ideas that become trendy aphorism in liberal circles without any critical engagement with the subject. From comedian Aziz Ansari, who wrote a book on modern dating and consent, to Homegrown Co-Founder Varun Patra, all these men had carefully branded themselves into the new marketable “wokeness” of being a feminist. Feminism was no longer a set of values, principles, and positions. It was a brand.

Yet all these men, when confronted, resorted to the same excuses: they were “good men” who just misread the situation.

Comedian Hannah Gadsby recently spoke about the trope of the good man as “garden variety consent dyslexics. They have the rule book, but they just skimmed it, you know…” The problem was that “men were constantly moving the goalposts to place themselves on the excusable side.” Shantaram took an active role in the online name and shame campaign against Manik Katyal, another serial predator, yet he refused to see his own behaviour in that light.

Shantaram wrote to me, “I’ve become increasingly aware of the rights and privilege… That’s thanks in no small measure to the #MeToo movement.” As someone who had fashioned himself as a feminist, a social crusader, and has leveraged the social cause to build his career, this claim that he needed #MeToo to recognize his privileges, or that #MeToo was a teachable moment is very telling. Shantaram is not a kid; he is a middle-aged man who should have known better.

But historically men have always had the superpower to retreat into innocence by becoming boys who don’t know any better. #MeToo is about women breaking ranks, breaking their silence, at a great personal and professional cost to them. It’s not about setting new norms or teaching men. Audre Lorde says, “Women of today are still being called upon to stretch across the gap of male ignorance and to educated men as to our existence and our needs. This is an old and primary tool of all oppressors to keep the oppressed occupied with the master’s concerns.” It is not the survivor’s task to educate men like Shantaram.

To quote Lorde again, the demand placed on women to teach men is “a diversion of energies” and “a tragic repetition of racist patriarchal thought.”

Two: The inarticulate woman

If Shantaram knows that no means no, he also knows when to use that infamous excuse that she did not “clearly say no.” This is the second tactic of disavowal. Each polite, curt rejection and refusal is read merely as another opportunity to pursue and try again.

Shantaram says, “If someone said no, I would not keep on asking her.” But people rarely say “no” and more often than not use polite, courteous, and innocuous language to convey their reticence, doubt, and refusal. Common courtesy, politeness, and unwillingness to be rude become openings into which his chase continues. But since she may not have said the word “no,” and since she may have used vague and deflecting language so as not to appear rude or obnoxious but still clear and specific, she becomes fair game. Like a Bollywood hero, singing and dancing around a young woman trying to escape his clutches until that final moment when she succumbs to his charms, her lack of enthusiasm becomes an invitation and she becomes responsible for his continued overtures.

The burden is shifted. The waters are muddied—intentionally.

He calls the entire situation a result of misunderstandings;

“It’s such a pity to lose friends over unresolved misunderstandings.”

He blames the misunderstandings on poor channels of communication.

“I so dearly wish we had a better channel of communication at that time so that we didn’t have to end up using this channel today.”

It is all a big mistake and a consequence of the women’s misreading of who he is and what he was trying to ask her for. But it is impossible to miss the dissonance and disconnect here. This was not an unresolved misunderstanding as the young woman pointed out:

“He kept messaging me in an overtly friendly way over the years.”

The channels of communication were clearly open and available, after all. That’s how he repeatedly reached out to her. So much that she eventually had to block him from her social media channels to stop his persistent personal and romantic advances.

Shantaram was not only writing himself out of any responsibility; he was also translating the women’s experiences to his audience, taking serious allegations and rewriting them into innocent and well-meaning acts. The language of “consent” and “miscommunication” that Shantaram uses also contributes to a violent erasure of what the women really experienced: fear, shock, violation, breach of trust, and creepiness.

Finally, entirely tangential to the egregious issue at hand, Shantaram adds, “It is entirely possible that I didn’t think much of my accusers’ work and therefore I must have “subtly dissed” it.” She isn’t even a good photographer/artist and, “therefore,” instead of advice, suggestions, constructive feedback, support ideas, and critical comments, she deserved a “subtle dissing.” Apparently, she deserves it, no less. When Shantaram includes the claim that “I didn’t think much of my accusers’ work,” he is carefully crafting the narrative of a talentless young woman responding to a bad review with a harassment allegation. Those who commented on Shantaram’s post were quick to pick up on these threads. The women were called “unscrupulous,” their allegations “frivolous,” and criticised for not being able to deal with critique.

The language we use to think about and counter heterosexual explanations of consent remains skewed in favour of the powerful. The language, the medium, and the space available for survivors to speak about sexual harassment in any meaningful way remain inadequate. This cognitive poverty of language is not an anomaly. It is a function of a culture that produces it. The more I read men and their explanations of innocence, the more it becomes clear that the language we use is inherently biased and produces social acquittals for men. It is structured to confuse, obfuscate, or titillate. As Constance Grady writes, “I have found that the less specific my language is, the more invisible the violence becomes. But I also worry that the more specific I get, the more sensationalized my language feels.”

Three: The muddy waters

There is something shocking, arrogant, and privileged about a man who can claim that he “cannot place the details of the conversations we had, it seems that we have known each other for years” about an incident that deeply traumatized the women he harassed. In his direct exchange with me, Shantaram extends this argument: “While I find myself short of information to place the incidents in context, nobody should feel they have enough factual information to perfectly analyse the situation.” This is a bold claim and one designed yet again to undermine the credibility of the accuser. The claim is simple in its brutality: even the woman he harassed cannot claim or have “enough factual information to perfectly analyse the situation.”

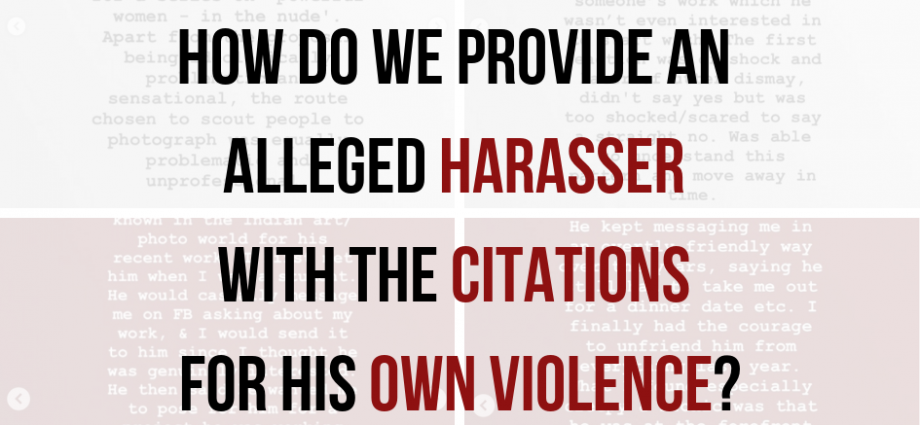

How do we provide an alleged harasser with the citations for his own violence?

Here Shantaram resorts to the need for “facts.” He employs the classic “he said vs. she said” defence. One of the most powerful advantages a man has over a woman’s testimony comes from the very private nature of sexual harassment situations. It is precisely the private nature of these events, the fear of retaliation, and the consequences of being identified as a victim that silences the women and enables men to publish public denials and muddy the waters.

Obfuscation and erasure go hand in hand.

While Shantaram claimed that “this isn’t “about me,” right?” in both his post and follow-up comments to me, the entire episode became about him, his perspective, his intentions: “I still maintain that no means No” and “I believe I know how to recognise it when told to me” and “I always try to conduct myself in a manner that is exemplary” and “I need some time (and context) to understand how this could have happened.” It was I, I, and more I with barely a reference or consideration of the consequences of his actions or what his accountability would mean in this case.

Four: It’s just my job

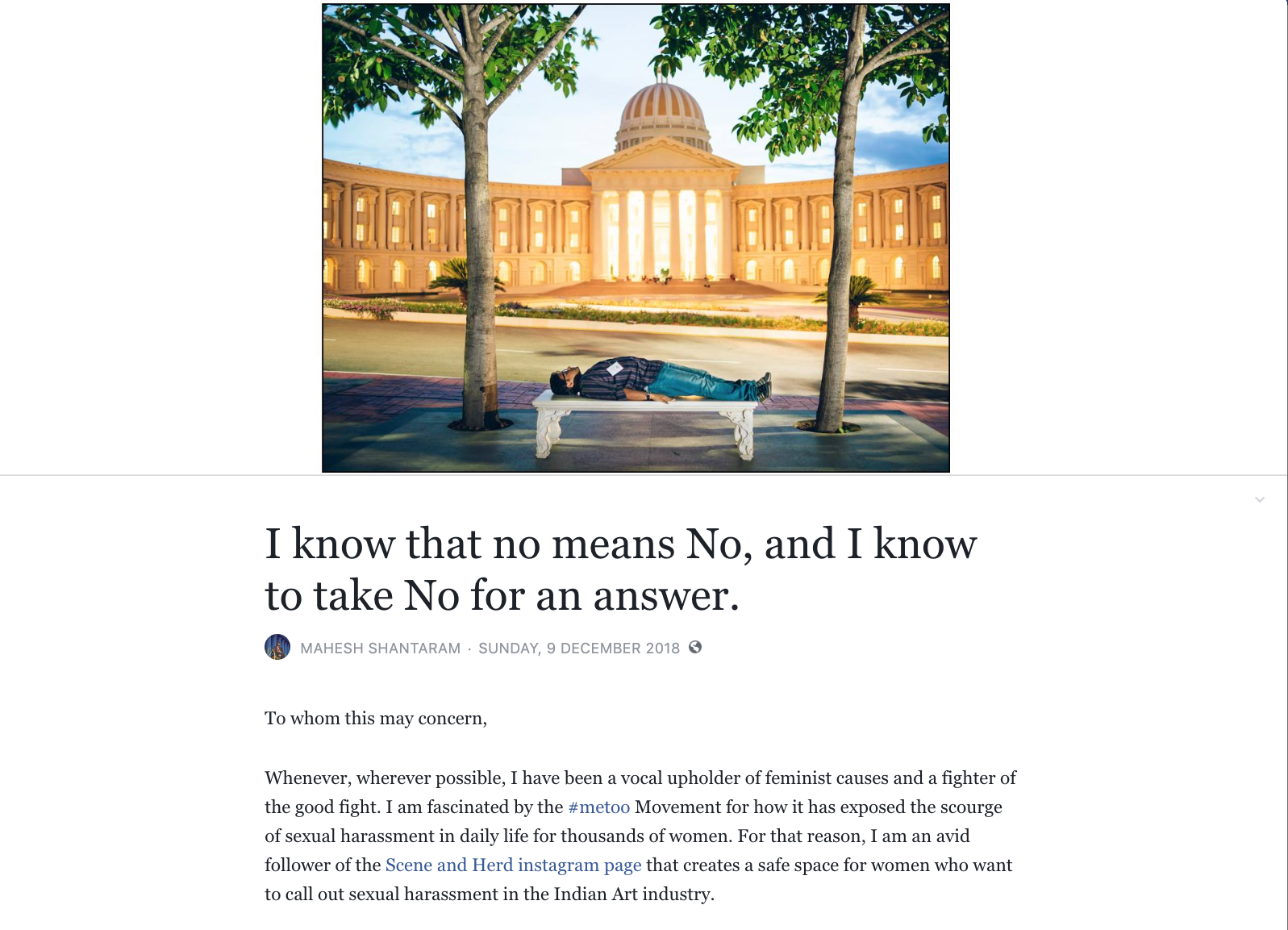

The so-called misunderstanding with these young women begins because of an assignment. In 2015, Shantaram was commissioned by Arte TV for a project called “Forbidden Love.” He confirms that he approached many women to disrobe and pose naked for this project. The allegations make it clear that both the women were much younger than him. One of them explicitly states that she was still a student when he reached out to her.

In his words, “I was free to express the theme in any way I wanted. Well, with a loaded title like that, I wanted to take it somewhere I would otherwise dread to go. I requested several women—whom I’ve known on some level—to sit for my portraits. And yes, this led to some awkward conversations, no doubt. What is said about the proposal being “ideologically problematic and sensational”—I agree. The concept was not the most convincing back then, and it bombed. In retrospect, to make a series of portraits of “women across the country” is pointing towards a good idea and I intend to pursue it.”

First, Shantaram dismisses his methods to scout women and any possible fallout from this as merely being “awkward.” Second, he concedes that the project was indeed “ideologically problematic and sensational.” But in the next statement, he disagrees with his own position and redeems his idea: “In retrospect, to make a series of portraits of ‘women across the country’ is pointing towards a good idea and I intend to pursue it.”

And finally, perhaps the most egregious attempt to muddy the situation was when Shantaram argues that it was all just “well-intentioned persistence” in the face of her refusals as “a photographer would, for access and nothing else.” That is, he was just trying to do his job. This argument found resonance even with women who supported Shantaram: “Access isn’t handed to one on a platter, is it?” Professional persistence has become a euphemism to excuse all sorts of unethical, underhanded, coercive strategies used for gaining access, compliance, and consent from reluctant subjects.

It speaks to a crass reduction of the subject into an object, a prey, one that the photographer hunts employing any and all means to achieve his aim. Coercion, persuasion, and trickery all become subsumed in the language of access to just “get the story” at all costs without any concern for the well-being and dignity of the people concerned. It is a mindset that simply wants what it wants with no regards for the consequences to the other.

SO WHAT DID THE WOMEN SAY?

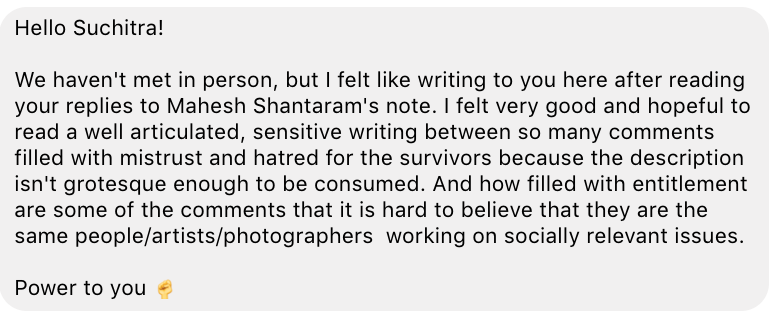

After my comments on Shantaram’s post, I received a series of messages, mostly from young women photographers and artists, expressing how toxic his language was. Many others wrote to me about their experiences with other photographers in the industry, serious ethical breaches they had witnessed both by Shantaram and other men who supported him. A young artist sent me this message on 11 December:

“We haven’t met in person, but I felt like writing to you here after reading your replies to Mahesh Shantaram’s note. I felt very good and hopeful [reading] a well-articulated, sensitive [response] between so many comments filled with mistrust and hatred for the survivors because the description isn’t grotesque enough to be consumed. And how filled with entitlement are some of the comments that it is hard to believe that they are the same people, artists, photographers working on socially relevant issues.”

Many of the women I spoke to narrated terrible stories, instances, and interactions that only confirmed the culture of silence. They were mostly young students or 20-something artists and photographers trying to find a place for their work in a very small and closely-knit community of artists, editors, and gatekeepers.

How you treat a person especially when constructing visual projects is absolutely critical, more so if you have fashioned yourself not just as a photographer but also as an activist speaking to social causes. It is especially important to note this statement made by one of the women who spoke about Shantaram: “What I found especially creepy and ironic was that he was at the forefront of the social media campaign to name and shame Manik Katyal for being a serial predator while behaving in a similar manner himself…”

Manik Katyal, founder and editor at Emaho, sued 36 women who accused him of sexual harassment and was back in public life curating a three-day photo-book festival, The Kitab, in Almora in September 2018. A newspaper report described the festival as “a part of [which] was dedicated exclusively to the women who live there. Manik tells us what the festival was about and how it impacted these women” without any irony. The “feminist warrior” fighting the “good fight” appears yet again.

While the Indian art world recently issued a statement about creating safe spaces to report harassment, what remains striking is the fact that many of the signatories continued to support or signed a statement seen as defending cultural critic and lecturer at Asian College for Journalism Sadanand Menon, then facing serious allegations of sexual harassment. Many of the men accused of serious violations continue to enjoy the protections of their privilege, and very few have faced any real consequence. A student who recently graduated from an MFA program said, “I am just so disappointed in so many people. These are people I respected, aspired to be when I grew up. Now I don’t. I can’t respect people who hide behind due process and show no solidarity for us. I saw a man who taught us defending a photographer accused of harassment. It’s disgusting. Imagine if I now challenge this man, who is my teacher in our classroom, about his position, his friend’s behavior, and his work. What do you think will happen? I see how these men are allowed to act, harass without consequence.” The student who initially agreed to go on a record called two days later and requested that these lines be quoted anonymously. “I have to chicken out. I feel like this is a betrayal. But I have to repay a student loan. I don’t come from money. I am just starting out and I don’t want to be labelled difficult.”

Interesting that Dayanita Singh would sign this but also sign a statement defending Sadanand Menon. Funny how things change when a man accused by multiple people of sexual harassment happens to be part of your inner circle. https://t.co/2VzRWEt2RQ

— Karthik Krishnaswamy (@the_kk) December 23, 2018

Journalist Kristen Chick in her Columbia Journalism Review essay Photojournalism’s moment of reckoning interviewed over 50 women who “told a story of leading photojournalism institutions rife with bullying, where female photographers have accepted harassment as a cost of doing business, and a freelance labour pool where people are afraid to speak for fear of being labelled as difficult to work with. All of this as editors and directors have quietly ‘turned a blind eye.’” The men accused—Antonin Kratochvil and Christian Rodriguez—have not faced any serious consequences. National Geographic’s editor Patrick Witty, who was investigated for sexual misconduct, “left quietly.” While women have spoken up, there has been no institutional response or consequence. Some of the most powerful women in photography have remained silent about the various allegations both in India and outside.

The faith in silences

For all the liberal outrage and statements in support of movements such as #MeToo, it is remarkable how silent media organisations and publications have remained around matters of sexual harassment and abuse. Many of the institutions that have supported Shantaram’s work, as noted above, have been silent to date. Since these allegations, Egaro Photo Festival has hosted Shantaram and The Guardian of London featured his up-and-coming book. Even after his public acknowledgement, there has been little or no outcry.

Whereas an outlet such as Mid-Day has given Shantaram print space to further spread his side of the story, deny and dismiss the accusers, and continue to position himself as a “feminist warrior,” the young women who were the target of his “attention” have not been approached to have their side of the story told. To paraphrase Sartre, we are all located in our time. Every word has consequences. Every silence, too. As I sit and reread these words, I can confront an artist’s words with mine. But how does one confront the silences of the many who continue to enable a culture of misogyny and toxic masculinity?

Whose arguments are heard, and what allegations are dismissed as mere misunderstanding, reinforces misogyny, reproduces and maintains a culture of shame, silence, and fear. When serious ethical breaches, unprofessional conduct, and sexual harassment go unchecked by those in a position of responsibility, and when the powerful refuse to speak up or hold those people and actions accountable, they create a political economy of silence. When you see your professor, teacher, mentor, boss, or editor defend the perpetrator and not believe those who have risked everything to narrate their story, it reaffirms the conditions that maintain these silences—whether it is harassing women, sexually assaulting them, or building sensational visual projects on the bodies of others.

Epilogue

It was Shantaram’s description of his “Forbidden Love” project, and the unease I felt when I had first seen other examples of his work, that led me to relook and examine his Africa Project as well. “Ideologically problematic and sensational” is how one of the women who narrated her experience about Shantaram characterised his work. There was a thread that connects Shantaram’s projects—the use and abuse of bodies to stage visually “sensational” projects that were “ideologically problematic.” “African Portraits” and the construction of “Forbidden Love” both rely on the allure of spectacle—advertising campaigns built to grab your attention whose political significance is often lost within this spectacle. That’s the subject of the second part of this piece.