Misogyny and racism as spectacle and performance: A critique of Mahesh Shantaram’s ‘The African Portraits’ and ‘Forbidden Love’

Suchitra Vijayan is a Barrister-at-Law, writer, photographer, and executive director, The Polis Project. She tweets @suchitrav.

When a project is constructed around nudity and equated with freedom, does a woman who chooses not to disrobe for any reason then live in permanent unfreedom? How does one photograph women naked and interpret that as “power” when women in India, especially Dalit and Adivasi, are regularly stripped as punishment? You can read part one of this essay here.

I first saw photographer Mahesh Shantaram’s work titled “The African Portraits” in August 2018 when I received the following message from him over Facebook Messenger.

“Hi Suchitra… You may (or may not) be aware of my 2016-17 project ‘The African Portraits’ which attempts to get under the skin of racism and xenophobia in India. I thought I got done with it last year but then when I was invited to write for a journal about the project, it gave it a new lease of life. Now I’m going to finish up the research (with 1-2 trips to Africa in the winter) and publish the whole story as a book in March 2019. Please do check out the campaign and let me know if you have any questions, thoughts. Could it be featured on POLIS? http://bit.ly/TheAfricanPortraits.”

I was immediately struck by the aesthetic—the lighting, the rendering in these images of Africans living in India, and the texturization done to make their skin appear darker. A series that was meant to engage with Africans living in India, their struggle to find a place in a profoundly xenophobic society seemed lost in the drama of lighting and staging these images. I had concerns about how these men and women were staged in potentially disturbing ways on landscapes marked by violence. While the work briefly referred to violence, there was no context, history, engagement, or articulation of how their presence in this space affected their lives. The images portrayed members of the African diaspora in India in poses with distant empty gazes. However, India and its visceral racism remained absent. These images could have been photographed anywhere: Delhi, Bombay, Accra, Nairobi, Addis Ababa, or Kinshasa. While the descriptions of the work regularly referred to racism, the photographs themselves did not articulate this message. The images were repeatedly described as an “intimate,” “visual reckoning of this minority community” that “paint a picture of loneliness, placelessness and a sense of hostility” and were “emotionally resonant.” There was a disparity between what was described and attributed to the photographs and the photographs themselves.

Does merely photographing the diverse African community automatically mean depiction, representation, or engagement with racism?

After an internal discussion, The Polis Project decided not to feature the work.

Four months later, in December 2018, two women published harassment allegations against Shantaram in the Instagram account Herd and Scene. Shantaram had allegedly scouted them to pose naked for his “Forbidden Love” project. In response to the allegations, Shantaram wrote a deeply dismissive and patronising Facebook post. In the process of explaining himself, he argued that he was just doing his job and was taking the project “somewhere I would otherwise dread to go.” I have undertaken a fuller analysis of this non-apology in this previous piece.

In his words:

“In 2015, I was one of the photographers commissioned by Arte TV for a global project called ‘Forbidden Love’. I was free to express the theme in any way I wanted. Well, with a loaded title like that, I wanted to take it somewhere I would otherwise dread to go. I requested several women—whom I’ve known on some level—to sit for my portraits. And yes, this led to some awkward conversations, no doubt. What is said about the proposal being “ideologically problematic and sensational”—I agree. The concept was not the most convincing back then, and it bombed. In retrospect, to make a series of portraits of “women across the country” is pointing towards a good idea and I intend to pursue it.”

Disrobing the regularly disrobed

Interpreting “Forbidden Love” to mean photographing “powerful women in the nude” is not pushing artistic, political, or societal boundaries. It is sexualising “powerful women” and reducing the idea of forbidden love to a bourgeois notion of sex, lust, and freedom. India’s sexual landscape and the political (often violent) repercussions of love, lust, and desire are inextricably linked to caste, class, and religion. In 2016, an inter-caste couple, Shankar and Kausalya, were attacked by Kausalya’s family. Shanker was hacked to death in public and Kausalya sustained severe injuries. In September last year two horrific caste crimes sent shockwaves across Telangana and a 13-year-old Dalit girl, Rajalakshmi, was beheaded in Tamil Nadu for rejecting the sexual advances of a 30-year-old man. The Kerala High Court in 2017, in what is now called the Hadiya “Love Jihad” case, gave a controversial ruling that gave the custody of a 24-year-old woman to her father for marrying a Muslim man. The court initially stated that Hadiya was incapable of making decisions regarding her marriage or conversion to Islam, a decision later overruled by the country’s Supreme Court.

When a project is constructed around nudity and equated with freedom, does a woman who chooses not to disrobe for any reason then live in permanent unfreedom? How does one photograph women naked and interpret that as “power” when women in India, especially Dalit and Adivasi, are regularly stripped as punishment? How can one interpret “forbidden love” to mean photographing urban, upper-class naked “powerful” women when love or desire for someone from a different caste or religion in India is often awarded with a death sentence? This method, gaze, request, and process remain deeply implicated within the conceptions of neoliberal feminism, constituting links to grants, commissions, and visibility. This is not storytelling; this is orchestrating a spectacle to enhance a career built on the bodies of others.

Shantaram concedes that “the concept was not the most convincing back then, and it bombed.” What does the word “bombed” imply? Did the concept bomb because it was conceptually oppressive and extractive? Or did it bomb because women refused to be photographed? Even if all the women he approached agreed to be photographed naked, would it be redeemed of all its problems just because the women consented? Would it exonerate Shantaram of this exploitation and sensationalization? How do we problematise the nature of consent and coercion? Shantaram’s projects are connected by the use and abuse of bodies to stage visually sensational images that are ideologically problematic. The African Portraits and Forbidden Love projects rely on the allure of spectacle. They are advertising campaigns built to grab attention and whose political significance is often lost within this spectacle.

Disrobing is always a question of power and society’s need to imprint shame on the body of women. Shame is also used to socially control, coerce, discipline, and punish. India has a long history of violent assaults, disrobing, and parading Dalit and Adivasi women naked. In 2007, a young Adivasi woman, Laxmi Orang, a member of the All Assam Adivasi Students’ Association protesting in Guwahati demanding Scheduled Tribe status for Adivasis residing in Assam was chased, stripped naked, and assaulted in public. While she was being stripped and assaulted, the police standing nearby did not come to her rescue. The next day the media flashed her naked pictures leading to public outrage.

The spectacle of disrobing a woman runs through much of Shantaram’s work from the incident that sparked his interest in the African community to the use of naked bodies to create sensational projects.

Spectacle and performance

Shantaram says he began shooting his African Portraits series after the “stripping of a Tanzanian woman in Bangalore.” Shantaram had stated at the time that he did not know that there were Africans in India and therefore he began this series.

Ethiraj Gabriel Dattatreyan, anthropologist and lecturer at Goldsmiths, University of London, recalls how the Africans living in India became a news story. Close to midnight in January 2014, Delhi’s law minister Somnath Bharti led a raid in Khirki Extension in South Delhi directing police officers to act against a “den of vice” and charging primarily the Africans living there with running drugs and prostitution rackets. This was not an exception. Several black African students had previously been attacked in a series of hate crimes throughout the country.

Khoj, an arts collective, has been located in Khirki Extension since 2002. Khirki is also home to one of the largest and diverse communities of Africans in India—Nigerians, Congolese, Ugandans, Kenyans, Somalis, and Rwandans. Students, artists, sex workers, and transgender communities all live here alongside segregated spaces where gated upper-class communities live. Many Africans here do not feel welcome. They regularly face discrimination, pay higher rents, and are often targets of violent attacks.

From 2012 to 2014, Dattatreyan spent time building relationships with the Somali and Ivorian communities in India. According to Dattatreyan, the journalists finally began to arrive when the state-sponsored and legitimated violence became a regular phenomenon against these communities.

“All of a sudden many of Delhi’s journalists and photographers decided that this African story was important,” Dattatreyan recalls how he became positioned as a gatekeeper. There was a lot of interest in “gaining access,” “shooting,” and “telling these stories.” Dattatreyan was well aware of what the news cycle wanted; often many of the journalists and photographers who descended “made a horrible mess.” He states that he observed a pattern, “There was a hunger to fulfil a particular story.” The many journalists that reached out to him to gain access to these communities often made no attempt at being human to the people they were photographing. “They were looking for people who could become a story,” he said.

It was against this background that Khoj created and curated the “Migration and Memory” project where various artists and photographers including Shantaram worked on themes related to the project. The residency was built to understand and produce work on and about the African communities that lived next to them. Some of Shantaram’s other African portraits were shot over a period of five weeks during the Khoj residency’s Coriolis Effect Migration and Memory project in 2016.

The “Coriolis Effect” project was designed “to activate the social, economic and cultural relationship and historical exchange which exists between India and the continent of Africa.” As Khoj described: “Globally, we have borne witness to the forced displacement of thousands of people from their homelands, and locally we have first-hand experienced the trauma of relocation… Through this project, we are also interested to activate conversation around topics of trade and labour flow, language and musicscapes, informal communities, asylums and voyages in the context of India and Africa.”

Persis Taraporevala was the critique-in-residence when Shantaram was at Khoj in 2016. Taraporevala is currently based in the Geography Department at King’s College, London. Her research interests include citizenship rights and the enactment of democratic processes in the urban landscape. As a critique-in-residence, she engaged with Shantaram throughout the residency. Taraporevala was uncomfortable with Shantaram’s work from the beginning. She states that early on she and others at Khoj had serious concerns about his work.

Shantaram was there to make images and create a body of work; the stories of African life in India seemed ancillary to the photographs. Shantaram regularly employed the language of how it was important to shed light on the African communities in Khirki. You need to be seen was essential to his pitch.

After having seen the initial images and his practice, Taraporevala discussed the photos with Shantaram. She asked questions about his process, how he photographed the images, and discussed the ethics of photography.Taraporevala was concerned about how the subjects were posed—the positions, how they were made to stand, look, and gaze into an empty space, and how they were made to hold each other. She felt Shantaram’s portrayal showed them as weaker, stripped of agency, and not capable of telling their own stories.

Taraporevala specifically asked Shantaram whether the people he shot had the freedom to choose how they were depicted. Shantaram responded that the images were staged and that he had directed the people to pose. He said that there should be something strong about each image, and he was creating it. There was no commitment to investigate or tell these stories; instead, it was about making powerful images.

Malini Kochupillai, an independent photographer and urban researcher based in Delhi, was also at Khoj with Shantaram. For her, Shantaram’s work was one-dimensional, and it sensationalised the experiences of the community and always portrayed them as victims. “Photographing dark-skinned people in dark places in the night is technically difficult. He tapped into this to make technically well-made photographs,” she said.

Here the visuals and perfecting a lighting technique took precedence over people and their history. In this tired and tested formula, “seeing and showing” was offered as the solution for all forms of discrimination, oppression, violence, and racism.

American-Ethiopian writer Maaza Mengiste has referred to such techniques as “exploitation in post-production.” In her talk in New York last year, “Unheard of things—the Vocabularies of Violence,” she discussed how lighting and post-processing techniques like posterizing and texturizing are used on the faces and bodies of brown and black people who are victims of war, famine, poverty, and violence.

They are often made to appear darker.

She stated, “What is it that we are supposed to be seeing of this human being? What is being emphasised here through that process? It’s really disturbing to me that this is being done with certain groups of people. Why is a photographer doing this?”

Seeing Shantaram’s portraits, I had similar questions. Why was the African diaspora being photographed in the dark? What was the function of darkness? Was it just technical or was it a medium to tell a story?

Frantz Fanon wrote of his experience as a black man in Europe as “an object in the midst of other objects.” He wrote about the loss of self as “an amputation, an excision, a haemorrhage that spattered [the] whole body with black blood.” Shantaram’s series similarly reduces the people he photographs to objects among other objects. The amputation, excision, and haemorrhage are all inflicted through the process of scouting, constructing the scene, lighting, and photographing it. Then came the post-production and the accompanying textual commentary.

During the residency, Taraporevala and others at Khoj tried to constructively critique Shantaram’s methods to no avail. Taraporevala said Shantaram always became defensive about his work.

Pooja Sood, director of Khoj and who usually ran the workshop, was away during this period. The gender-age dynamic also played an important role in how work was critiqued, reviewed, and challenged. Shantaram was also the only Indian man in residence. While he spoke politely, he was always dismissive in his responses according to Taraporevala, who characterised his behaviour and response to her critiques as “gaslighting.”

According to Kochupillai, Shantaram had an air of male entitlement “so ingrained in the attitudes of upper-caste and upper-class men in this country,” she said. Kochupillai said of Shantaram: “His mind was quite made up in that what he was doing was quite amazing work from the get-go. There was no doubt in his mind that he was doing God’s work.”

Taraporevala had two long individual conversations about his work, practice, and process. At the end of these various conversations, she said that “she felt drained.” She added, “I felt like I had created a Frankenstein monster. We had now taught him the language of critique, power, and representation that he would now use to manipulate, sell, and leverage these pictures. He now knew how to use the language, without critically engaging with the ideas.” Taraporevala also found serious problems around consent coupled with his refusal to see the humanity in those he photographed.

Taraporevala’s critique of Shantaram’s work and other similar projects points to how the optics of socially relevant causes can be leveraged to project oneself as morally superior without any critical thinking. Taraporevala also pointed out that handing over the power of representing a community to someone who lacks real empathy was the actual abuse. Shantaram’s African Portraits was one of the only widely published visual representations of the African community in India. To be their voice is a powerful position to hold for someone so insensitive.

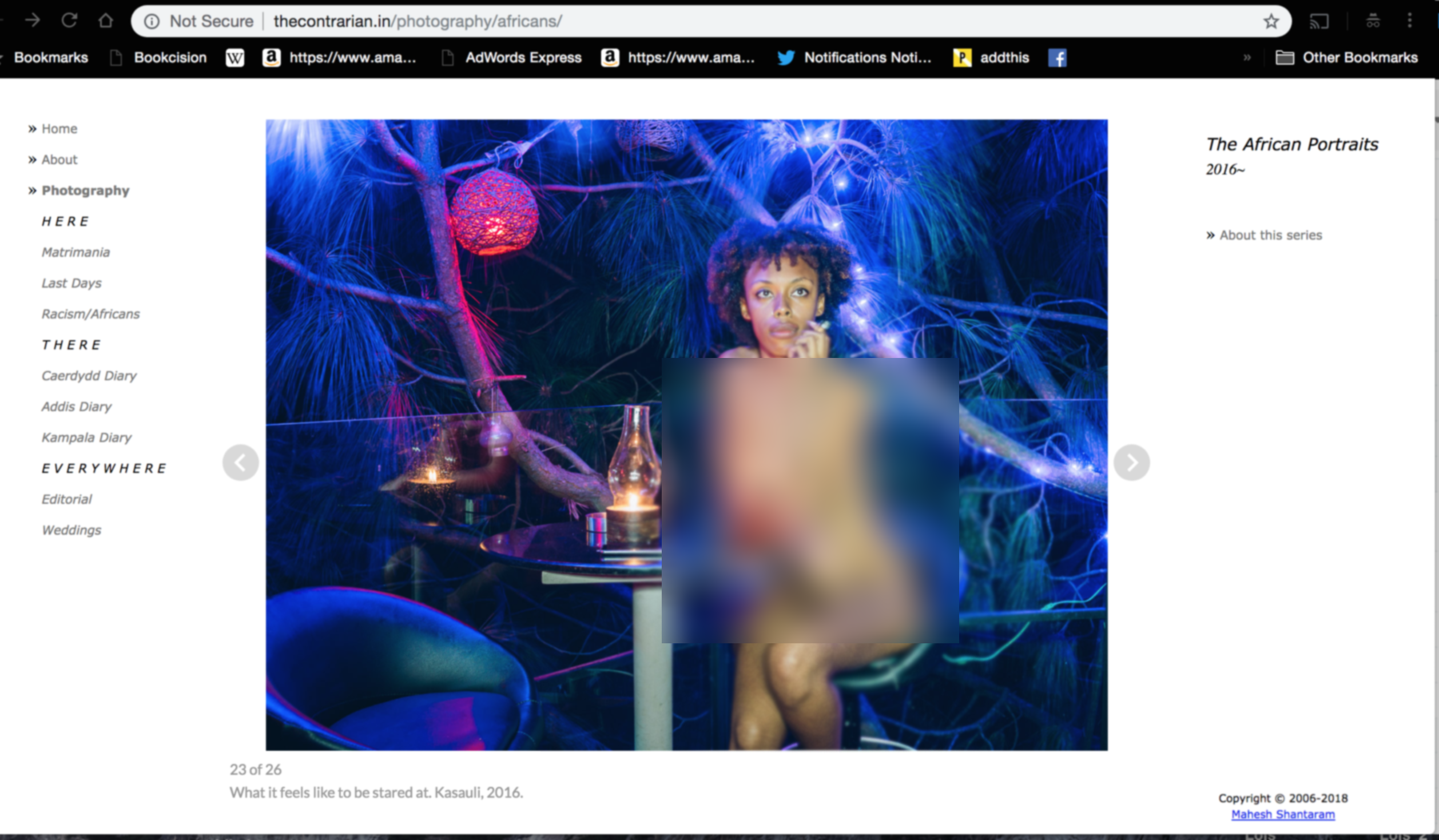

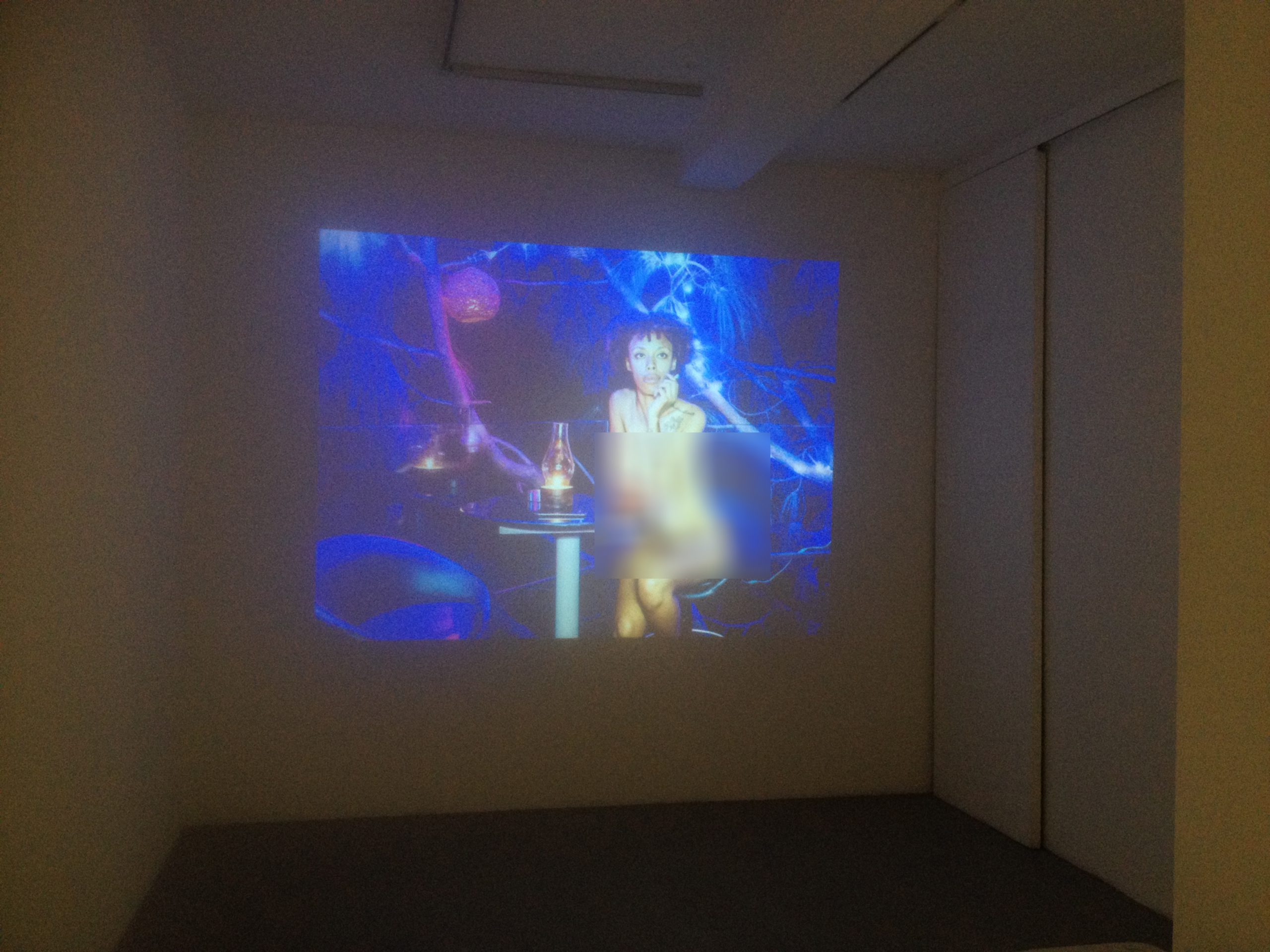

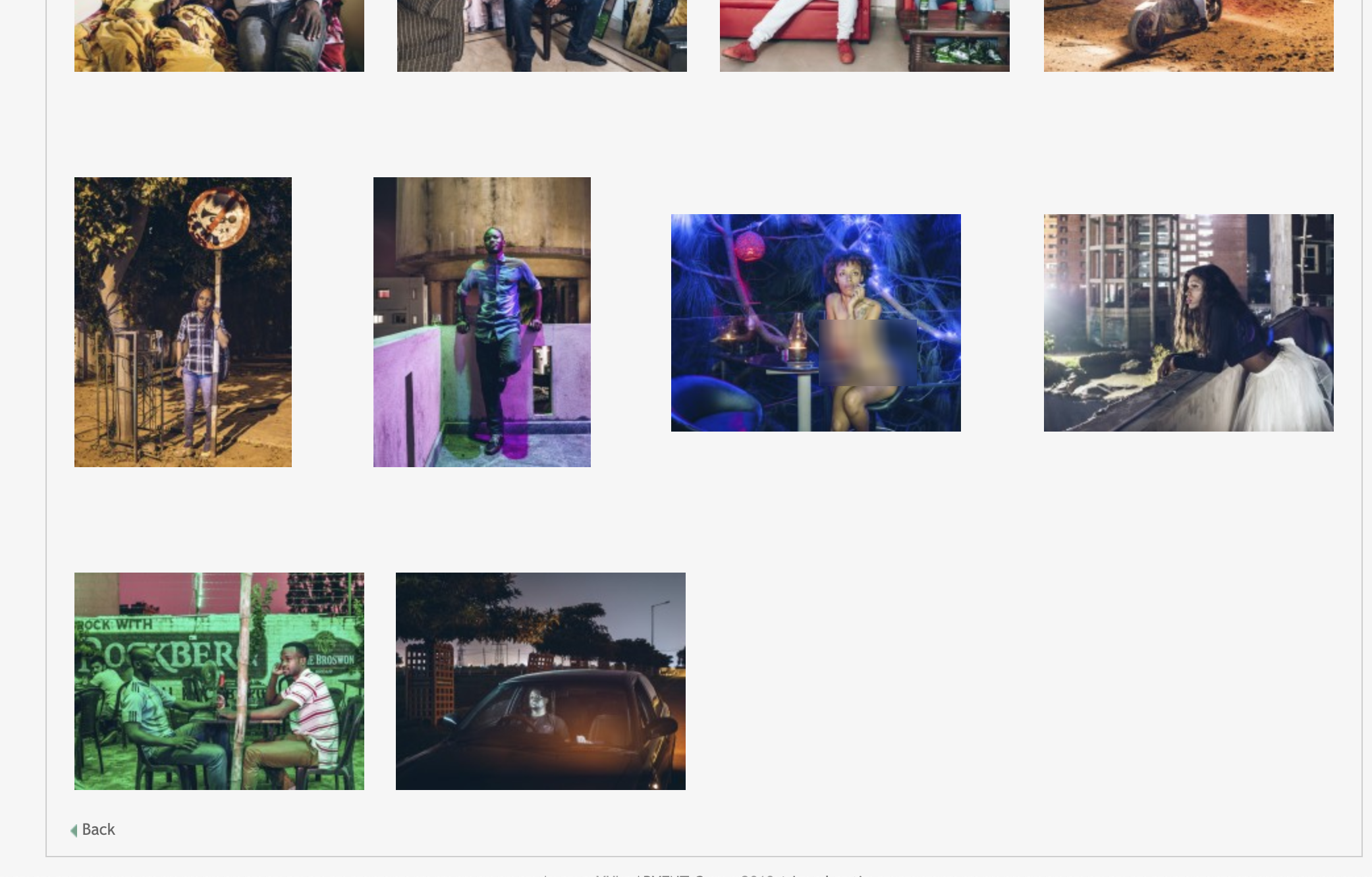

On the day of the Khoj finale exhibition in September 2016, amongst the African Portraits was a seemingly innocuous picture of a naked black woman. Taraporevala was shocked to see this nude photograph. The woman was not African but an African-American tourist then travelling in India who Taraporevala had met and socialised in Delhi.

At the Khoj exhibition, the photograph was shown unnamed, without any context or clarification that the woman was African-American.

The image appeared on Shantaram’s website as [Image] 23 of 26. Shantaram removed the image after The Polis Project emailed him with questions about the images. The image, when it appeared on the site till 10 February 2019, had no name or context. The caption just read, “What it feels like to be stared at Kasauli, 2016.”

When Taraporevala raised the question with Shantaram on the day of the exhibition, she said that he made a random remark and walked past her.

Kochupillai, who was also present at the exhibition, said, “The story Shantaram gave us was that she is the one who wanted to disrobe for the camera. She is the one who wanted to be photographed this way. I haven’t heard the woman’s version.” It wasn’t the nude that bothered Kochupillai. Her discomfort was with “a context-less nude in a body of work about the African diaspora in India.” She continued, “To me, this is typically to create something for the shock value, a vacuous move.”

What does this image represent? How is photographing an African-American woman naked a part of the story about race, xenophobia, discrimination, and violence? If this image was about interrogating “gaze” or how the Indian society stares at, looks at, and perceives black people then does that narrative require her to disrobe? Did Shantaram ask the men to disrobe to articulate the sentiments of violence, power, and gaze? What function does the nakedness of the black woman serve? Are the experiences of an African person in Khirkee the same as those of an African-American tourist in Kasauli?

Alexis Ward is a black American artist and model who was travelling in India between July and October 2016. She was introduced to Shantaram by her friend Veda Laayla through social media. Ward actively engaged and spoke about racism, colourism, and the Black Lives Matter movement in America and Laayla wanted to extend these conversations about racism and colourism to India. Ward said she did not know who Shantaram was and is not sure how he came to know about her. She decided to speak to him after Laayla told her that Shantaram was a journalist who was shedding light on racism Africans faced in India. Laayla suggested that she discuss her experiences in India with him along with her work as an artist, activist, and a model. “I trusted him because of her. I knew her for over two years and had already met her and her family,” Ward said.

According to Ward, Shantaram wanted to photograph her for a profile piece on her experience in India. Shantaram told her that his work focused on Africans in India and that including Ward’s perspective as a black American would be a good contribution to the series. “Any opportunity to speak out about my community and my people was important to me. He seemed a credible source, and I wanted to make that connection as an artist with someone working on issues I cared about,” she recounted.

Soon after their initial conversation, Shantaram came to Kasauli, a small hill town north of Delhi, and spent a day with Ward and Laayla’s parents. “We were in mixed company the whole day and we all had dinner together,” she said. Ward spent a lot of time talking to Shantaram about her experience of being black, her relationship with other black Americans, and what it meant to be in India, a conversation she remembered Shantaram recording.

When they discussed the photo shoot, Ward said, “I asked him what’s your idea, what’s your concept, what is that image that you want to put out?” Shantaram suggested that he would like to photograph her on the hotel rooftop. Later as they discussed the image he casually suggested, “If you don’t mind being nude, that would be good.”

Ward was a little perturbed, she recalls. “I don’t mind being nude. I am a model. I don’t have any shame about my body, I love my body, and I think it is powerful. For me, nudity was not a negative thing.” However, this request did not make sense to her. “I kept asking, what is this story that you [Shantaram] are trying to tell with my nudity, how does this relate to everything that I have told you about my story? My story had nothing to do with my body or nudity,” she said. “In response Shantaram basically said,” she told me, “the nudity was going to make people look at the black body and blackness and put that in front. He said India had such problems with nudity.” She added, “I was very put off by the fact that he brought it up in the first place. I regret it now. I wish I was able to speak up then.”

Shantaram then asked Ward to hold a cigarette in the frame as he started photographing her. Ward is not a smoker, and the cigarette had no connection to her story or their conversations. She said, “That was when I felt something was really, really wrong with this. But I was already in it and felt I couldn’t back out. As soon as he gave me the cigarette, I immediately felt this was wrong. This was wrong. I was purposefully trying to cover up and he kept trying to open me up, open me up, and open me up. He kept saying, “You are hiding. [It] looks like you are trying to shy away from the camera. You look like you are not really comfortable. Feel relaxed, try and take a deep breath.” I was like, dude, I get it, but come on.”

After this, they moved to another part of the roof and Shantaram continued to photograph her. Ward said that she again felt uncomfortable and kept trying to “not show too much.” According to Ward, he told her, “Try putting your arms down, you look so uncomfortable.”

As they came to the end of the shoot, Shantaram told Ward the images were going to be shown in the gallery. She told me, “I was like what gallery, what show?” Shantaram told her there were other women involved in the shoot as well and she was not the only one. However, there are no other nudes in the publicly accessible African Portraits series.

Ward stated, “This whole thing did not make any sense to me. I really did not know how to defend myself. It didn’t feel good at all. It was all already happening. But I did not know what to say. He was already there, we had already been talking for so long.”

Shantaram invited her to come to New Delhi for the exhibition but she refused. She said, “I didn’t go to Delhi because I didn’t trust him. I was nervous, I wasn’t even sure if the exhibition was real. I felt that if I went I was going to end up in some kind of a trafficking situation. I was a sole, female, black traveller in India.” Ward adds that there was no conversation about how the photos were going to be used and Shantaram never told her if they would be sold. There was no contract or release signed for the images. In fact, she became aware of the existence of [Image] 23 of 26 online only after The Polis Project informed her of its existence in an email seeking an interview.

She said, “I feel awful knowing that my image was out there without my knowledge. India was already a tough place and I had a lot of painful experiences. Apart from the encounter with Mahesh, [some] men in Pushkar tried to kidnap me. I feel ashamed with myself. I wish I had known better, I shied away from confronting it. I thought it [had already] happened [so] let me move on. I kept telling myself maybe it’s just this guy who had these images on his computer and that’s that. I told myself I wasn’t going to see him again. At that point, I wasn’t even sure if he was a real photographer or not.”

A few weeks after the shoot, Ward sent Shantaram a message telling him not to publicly release the photos. She told him to “refrain from posting them.” He responded agreeing not to. In a conversation over Facebook Messenger, he told her, “I haven’t shared your wonderful portrait anywhere other than the weekend show in Delhi last month, and at a university talk I gave later. I hope I can submit it [for] professional reviews where my work will be seen by industry professionals. That’s connected mainly with my career growth.”

Ward added, “I knew it was too late as far as whatever gallery showing happened in 2016. But I specifically asked him not to show the images after that. He messaged in 2017 saying a poet wanted to use the image but I never responded.”

When The Polis Project emailed Shantaram for a comment on the discovery that he had misrepresented Ward in his African Portraits series and whether he had also not secured her consent for further display or sale of her photographs, he had the following response. He said that he was not misrepresenting an African-American because one of his initial portraits was of a “Jamaican medical student that I usually use as an opener to the series.” He also stated that he and Ward “collaborated to create this portrait and express the idea of ‘what it feels like to be stared at.’” He added, “The image in question has never been for sale—neither for art buyers nor publications. I keep it as part of my portfolio because I believe it supports the larger statement I wish to make with this work. Since I’m aware of her concerns, I have taken utmost care not to send it around for competitions, publications, and events where I have no control over how it can get used. For the time being, I have also removed this image from my website.”

Based on our interview with Ward, Shantaram never asked her for permission to display her picture on his website. Contrary to Shantaram’s claim, in spite of Ward’s request to have the image retracted after the initial gallery display, it has since been exhibited at Gallery 320 in 2017. The image was also available for sale on the Agence VU website till 10 February 2019. It was removed hours before this essay was published. The Polis Project has also reached out to Agence VU for comment but has not received a response yet. Ward summed up the impact of this event saying, “Now that I know people have seen it, that it is still out there, it’s going to take me time to process what it means for me right now. But I am still ashamed by that experience for sure.”

Contrary to Shantaram’s claim, Alexis Ward’s image print was on sale on the Agence VU site. The image was removed on the 10th of February from their site after The Polis Project emailed Shantaram and Agence VU.

Ward added, “I feel extremely disrespected by what he has done. The original intent to share my story in a way to uplift my community was the only reason I agreed to work with him. I thought he was genuinely using his craft to do good for members of the African Diaspora. To know that he has been profiting from this act of violence angers me.” Ward’s image on Shantaram’s website and in exhibitions has been displayed without her story or any other clarifying text. The naked image, to our knowledge, has always been exhibited unnamed, accompanied by a misleading caption. Ward added, “Erasing my voice is yet another instance of racism towards my people, and that is totally unacceptable.”

Based on Ward’s experience it is easy to see how her consent was manipulated and later disregarded. While the image bears a title suggesting that she felt disrobed by the eyes that stared at her in Kasauli, the real objectification happened when she was disrobed and photographed in an uncomfortable situation and made to pose for a series where her identity was misrepresented to and obfuscated for a wide audience.

Like the Forbidden Love project that proposed the use of naked bodies as a trope, here the unclothed body of a black woman was used as a spectacle. Shantaram scouted young women to pose unclad for his Forbidden Love project to depict freedom and power. Now nudity was being redeployed to represent a violent gaze on a black woman’s body. Nakedness became a salacious blank slate where any meaning—freedom, fear, desire, death—could be conjured and forced onto the exposed body of a woman. In the end what is produced is a spectacle, not a consideration of what it means to be a black man or a woman living in and navigating India.

This fetishised use of naked bodies of black and brown people, especially women, has a long orientalist, colonial history. Shantaram’s work fits into a long history of photographing and projecting black bodies as sites of victimhood. It represents a culture of image making that enables people coming into spaces they don’t have relationships with—to sensationalise and cannibalise stories, miseries, and bodies and produce value for themselves. Shantaram is not an exception, he is the rule.

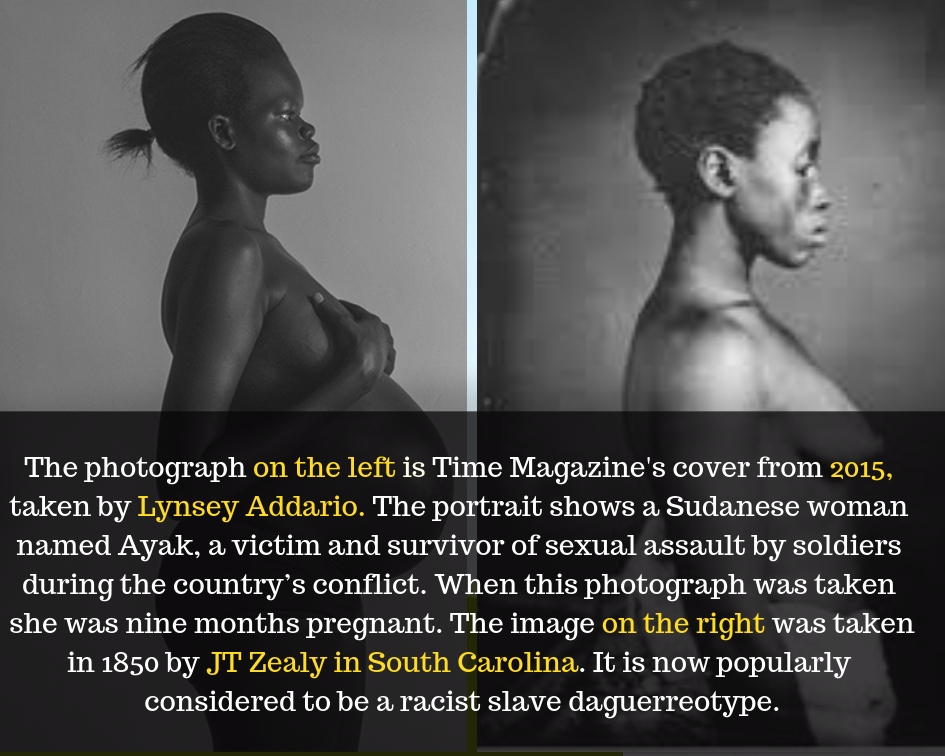

The photograph on the left was a Time cover from 2015 photographed by Lynsey Addario. The portrait shows a Sudanese woman named Ayak who was repeatedly raped by soldiers. She was nine-months-pregnant when she was photographed by Addario. The second photograph, by JT Zealy, was taken in 1850 in South Carolina. The Time cover was universally applauded—from Partick Witty, the former photo editor at Time and National Geographic (now disgraced due to various sexual harassment and assault allegations), to Claire Lewis, the UNHCR Goodwill Ambassador. Addario herself spoke about her process. She said, “Once I went over the guidelines with Ayak—in terms of how she felt about being photographed, given that her image would be seen by thousands around the world—I spent several hours with her… We sat down with Ayak, and discussed my vision for her portrait, and she didn’t hesitate at all; she understood what I was trying to convey, and as I photographed, I showed her the images on my camera to ensure she understood what I was capturing… It seemed that the very act of photographing Ayak and her unborn child gave her the opportunity to celebrate the very thing her perpetrators had tried to rob from her—her beauty and her dignity.”

The language of engagement and consent often violently hide and whitewash realities on the ground. Addario told a 17-year-old rape victim her “vision for her portrait,” and “several hours” was enough to connect, engage, get consent, and shoot.

Just as the slave daguerreotypes “sought to create specimens out of the slave population,” these present-day repetitions of the same visual cues and frames reduce black bodies to objects that can be stared at. How much consent can be read and inferred into these images when black people from 1850 to the present are constantly “forced to surrender their bodies to public scrutiny”—in the exact same poses over 170 years?

Pallavi Rao is a writer, researcher and Ph.D. candidate in the media school at Indiana University, Bloomington, who studies Indian journalism. Rao’s work studies how caste, gender, and class in contemporary India are mediated through English language news, popular culture, and social media, with a focus on ideological constructions of the upper-caste identity. Rao argues, “In one image hosted on The Wire, Kelvin, a business administration student from Tanzania, is dressed in black and sits indoors on a black leather sofa. The surfeit of these shades of black draws the viewer’s attention to the glossy surfaces of Kelvin’s face, his forehead, his forearm, in a way that fetishises skin colour. In his study of Robert Mapplethorpe’s photography, Kobena Mercer recognizes how images focused with such intensity on skin colour function as “racial fetishism” and that “black skin and print surface are bound together to enhance the pleasure of the white spectator as much as the profitability of these art-world commodities exchanged among the artist and his dealers, collectors, and curators.” Shantaram’s audiences may not be exclusively white, but in the rarefied upper-caste and upper-class spaces in New Delhi where these photographs have been displayed, the pleasurable consumption of othered black bodies is no less hungry than the consumptive white gaze.”

Rao continues: “Shantaram’s accompanying commentary about his series treads more disturbing territory in his fetishistic ignorance about African nations, their geographies, and their politics. In the same piece in The Wire, Shantaram describes his encounters with students from Malawi and Zimbabwe, suggesting that his own ignorance about these countries should be resolved by googling the names of the nations. Inexplicably, he also provides screenshots of these basic Google searches—as evidence of what? I am not entirely sure. Even more perplexingly as an endnote, he provides a link for readers to take an Africa Map Quiz, a game where readers can place African nations on a continental map. These are baffling infantile exercises of upper-caste innocence, one where the ignorant Indian reader is asked to imagine ‘Africa’ as a homogenous ‘Dark Continent’ whose mysteries need to be unlocked through a Google search. Worse, it trivialises the scale and intensity of violence faced by the students he claims to be in sympathy with and undermines how structural racism operates.”

“It doesn’t matter, let’s call her Maria, shall we?”

In October 2016, Shantaram presented his African Portraits in association with the Tasveer Gallery at the National Institute of Design. A guest who attended the talk and spoke to me under conditions of anonymity described it as “problematic” and stated that Shantaram “made many blanket statements on race and racism while his portraits acted as mere representations of his subjects. He even forgot the name of one of his subjects and said, “It doesn’t matter, let’s call her Maria, shall we?” The fact that he did not remember the names of some of his subjects was something that students had noted during his talk. He did get some difficult questions during his talk from the students who asked questions about the advertising aesthetic of his work, especially when dealing with that particular kind of subject. I do not remember exactly what his response was.” The incident was corroborated by two other people who were present at the talk.

“It doesn’t matter, let’s call her Maria, shall we?” is a far cry from the branding exercise that has accompanied the series. Shantaram said in an interview, “Journalists spend five minutes, I spend five hours to learn about them.” He also claims, “What these portraits do is put a human in front of you, we can all read a dry newspaper report and read about how to do and so did such and such. You look at a human being in front of you and they become real” (sic). An exhibition text says, “Each photograph in this ongoing project is preceded by the time shared between Shantaram and his subjects.” (See here and here.)

Shantaram in various interviews repeats these truisms about the importance of being seen, and by showing “them,” he repeatedly makes the claim that he is affirming “their humanity.” He states, “My African friends tell me I am giving them a voice.”

Shantaram’s exhibition press releases refer to him as a researcher and activist. Yet in almost all the interviews and texts, what we hear is Shantaram—why he created it, how he created it, and how he hopes to create a conversation. We seldom understand the people he shot. There is no in-depth engagement with their stories. At the most, we get a paragraph that empties the narrative arc at the doorsteps of helplessness. Abrupt fractures in the story and text often turn the people he photographs into caricatures to be gawked at. Shantaram also calls some of the images in the project “conceptual” but one is left to wonder: what is conceptual about racism?

How is violence, hunger, and racism “conceptual”?

Alessio Mamo, an Italian photographer, shared a series of photos on World Press Photo’s Instagram handle in 2018. The pictures showed malnourished Indians covering their faces with their hands in front of a table laden with fake food. Alessio then asked these individuals “to dream about some food that they would like to find on their table.” The work was widely critiqued. But the incident, like Shantaram’s case, brings forward two critical questions. First, what is conceptual about hunger, racism, or violence? Second, till 2018, before the public outrage, the work continued to travel. It received the “Coup de cœur” at the International Festival of Photojournalism Visa pour l’Image 2012 (Perpignan, France) where it was shown. It was exhibited at the Delhi Photo Festival in 2013 and in Paris in 2014. It was invited by La Quatrieme Image to exhibit the photos series. Why had the various editors and curators not questioned, critiqued, or rejected the work? Where was the critical intervention?

In March 2017 Noida race riots broke out after five Nigerian boys living in Greater Noida were accused of cannibalism. Huffington Post India reported that “the residents of the NSG Black Cat Enclave in Greater Noida searched the fridge of five Nigerian students on suspicions of cannibalism. This was after a boy, who was a resident of the enclave, went missing and died in a hospital later. The five Nigerian boys were between 18 and 19 years old.

The Noida riots happened just a few weeks after the Hindu right-wing politician Yogi Adityanath became the chief minister of Uttar Pradesh (UP). Soon after his appointment, slaughterhouses in UP faced closure along with a blanket ban on cow-smuggling. The consumption of beef was banned and a new spate of lynchings of Muslims began. The Greater Noida riots should be located within this rise of xenophobia and orchestrated public violence. It contributed to the new wave of violence against Africans, they were attacked in public places and their cars destroyed. The gory details of the attack were widely written about and photographs of the bruised students were splashed across various newspapers.

Shantaram photographed some of the survivors from the riots and one of them spoke to me earlier this month on the condition of anonymity. The survivor said they met Shantaram, discussed the project and consented to be photographed. “Mahesh said he was going to take the picture and publish the statement of what happened during and after the attack,” he said. “But,” he added, “Shantaram never informed me about selling the images or took my permission to sell my image.” He knew that Shantaram sold prints from The African Portraits but was not sure if his specific image were being sold. He also added that he had not signed any release forms for Shantaram.

Two months after the riots in 2017, Shantaram displayed The African Portraits again in another exhibition at Gallery 320 sponsored by Tasveer. Filmmaker Wency Mendes and Samuel Jack, the then president of the Association of African Students in India (AASI), and other students went to the exhibition and saw that Shantaram had photographed four of the five Nigerian boys accused of cannibalism and staged them next to an empty fridge. Members of the AASI and others including Mendes had up to this point worked very hard to keep the names and identities of these five boys anonymous. Their visual identities were hidden specifically so they could go on with their normal lives—walk on the street, go to the market and perhaps not live under perpetual fear of being attacked over the accusations of cannibalism.

According to Mendes, “This was information that should not have been made visible.” For him, this was visually shocking, unethical, and endangered the lives of the boys. “It is giving materiality to an absolute nonsense that an Indian society perpetrated. That image is not worthy of even an archive. It is a staged photograph that reaffirms the idea that this is where the human body parts were kept. It is in bad, bad, bad taste, as simple as that. That is where it starts and ends. I am with making things visual and visible, I understand that every artist has done that. [But] here it is just portraying known ignorance. There is no process in this work, it’s purely exploitative.”

At the exhibition, Mendes spoke to Samuel Jack of the AASI who along with the other students had serious concerns about the image of the four boys posed next to the fridge and the naked photograph of the African-American woman displayed in the exhibition. The AASI, according to Mendes, conveyed the message to Shantaram about how they thought both these images were objectionable. However, nothing happened after this complaint and the exhibition continued. One of the students who was present at the exhibition corroborated the events. He added that he was angry about the nude because many Indians already perceive Africans in a bad way: “They say Africans came here to do prostitution, they came here to do bad things.” For him, the images of the naked black woman in the bar only confirmed such racist impressions and he asked Shantaram to take the image down. He stated that everyone was angry and upset and Shantaram promised that he would take down the image and never publish it again. However, as previously stated, the image continued to be exhibited and appeared on his website, removed just hours before this essay was published.

Shantaram also made a two-minute video showcasing the “proprietary lighting technique” he used to create his Africa work. This video also prominently features four of the five boys accused of cannibalism. The video shows the boys being made to pose and Shantaram moving the lighting around and shooting. This video was also made available on Facebook and circulated widely. (The Polis Project is in possession of the video but decided not to share it to protect the visual identities of the boys.)

These are serious moral and ethical breaches. First, why would anyone pose these boys next to an empty fridge when their neighbours had broken in just a month before to check if the fridge had human body parts. Under what conditions was this consent obtained? Who made this exploitative access possible? Just as Addario had spent “several hours” with Ayak, Shantaram did so with these boys. If these stories need to be made visible, is this the best way to do so given how easily the images themselves could have become a visual hit list. Like the others I had spoken to, Mendes also found this work to be exploitative. According to him, it took the discourse away from the African experiences and into the realm of baiting for attention.

Wency Mendes argues, “There is a strong gaze that is constructed in building the ‘other’ and rebuilding them in our vision of the ‘other.’ The problem with the work is that it is constantly rebuilding and enforcing those lines. The technical beauty doesn’t come from the effective use of the medium. It is the constructed use of the medium which actually follows very racists norms. If you trace the history of art or beauty, it takes us back to its root—knowledge—and none of this is knowledge. This is the strange thing about the project; what are you making visible?”

What do such projects give back to the community where the image is made? What knowledge do they add? What learnings, if any, are passed on to the society where the image is made? Do people sign release papers for images to be sold as prints and, if so, do photographers like Shantaram and large art agencies and galleries share any of the money made from the prints sold? How do we justify the commercialization of mining and selling portraits of the vulnerable in the art world?

Where are all the critics?

Juan Orrantia is a Colombian photographer based in South Africa who, along with Prof. Dattatreyan, collaborated on a project on African-Indian solidarities. Orrantia’s work often straddles important questions of identity and representation. He was also at Khoj in 2015. Orrantia saw Shantaram’s portraits online. He has always been interested, he said, in how the body of work travelled widely without ever receiving any critical intervention which, according to him, is also a reflection of most photo editors and their sense of critique. “Showing images of Africans in India immediately makes people assume that the work is politically important. This uncritical reception of the work in itself is interesting.”

According to Orrantia, he wouldn’t criticize the work itself. He did not find the images interesting or appealing as these were basic staged portraits. Shantaram was basically sitting African men and women and photographing them, he said, “in what for me seems an unclear way. They tend to a simplicity that is contradicted by the bright lighting. As a result, I feel the portraits don’t say much for the claims the photographer makes. As a result, they rely on the texts and the imaginary sensationalism that brands politics and activism onto them and therefore the subsequent ‘appeal.’”

The work’s key problem, according to Orrantia, is it relies too much on people’s imagination, prejudices, and assumptions of Africans and their situation in India, which then become rebranded into a political appeal or call for action. A part of the problem, he argues, is how photo editors, in general, are not open to critical interventions and positions. Second, there is very little critically thoughtful work done about the African diaspora given their numbers and religious and ethnic diversity. So when there is a demand for a certain visuality to accompany violent headlines, we quickly rely on existing bodies of work without much thinking. Third, there is very little critical understanding of what it means to represent someone else. There is no consideration of who is photographing whom and why. What does it mean to be photographed as a black person in India?

For Orrantia, the more interesting question that needs to be teased out is how criticality gets subsumed by the rhetoric of “bearing witness” and “telling their story.” There is always a forced urgency attached to these situations and photographers are often refashioned into activists who become the sole voice of speaking for the larger diverse community. This is something that we see globally. In this case, “if you scratch the surface, we can clearly see that Shantaram has power,” Orrantia continues. “He is comfortable, he is Indian, and he moves freely through the country photographing these people who want their visibility and don’t want it at the same time.” Questions about class, caste, and access are not put on the table for discussion. It is perhaps a tad easier to criticize a white photographer who goes to these spaces as against a brown photographer in Latin America or India because brownness complicates the critique, or brownness becomes a reason not to complicate the critique.

Palestinian-American scholar Dana Olwan writes that “assumptive solidarities,” where we assume some kind of a level-playing field with no attention to structures of violence, are dangerous. While the power differential between a white photographer photographing a black person is very different from a brown man doing the same, we cannot discount the material and situational differences of their respective positions or the conditions under which they encounter each other. Sometimes being empathetic about someone’s experiences might mean not turning them into a story. Not every story needs to be narrated. There is no burden on anyone to narrate their trauma for us.

Without engaging with the complexities of what needs to be seen and hidden, the work itself becomes parochial, where we wrongly equate making images of someone to a political act. There are long and sordid histories of the representation of African persons and African-American persons that are not being considered.

Orrantia also referred to Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa’s 2015 essay that was republished in Aperture and looked at how some recent photo books that feature African subjects rehash pejorative tropes. Wolukau-Wanambwa critiqued Dutch photographer Jan Hoek’s New Ways of Photographing the New Masai. He also critiqued Viviane Sassen’s books Flamboya (Contrasto, 2009), Parasomnia (Prestel, 2011), and Pikin Slee (Prestel, 2014) and Cristina de Middel’s The Afronauts (self-published, 2012). While Wolukau-Wanambwa’s essay tore into the ways in which old tropes were being refashioned, Orrantia says such critical interventions still largely remain an exception.

Malini Kochupillai, the Delhi-based photographer, also pointed out that while people talk amongst themselves, there is no culture of raising critical concerns. Even when questions are raised the natural defensive response is, “They asked me, I was given consent.” She adds, “The real question should be to interrogate why photographers are able to produce work without thinking about the consequences. There was an utter, shameful lack of criticality in ways in which Shantaram’s work was promoted from the get-go. [But] more than Shantaram’s work, it points to how the art world talks about and promotes specific artists and artworks. This is problematic and symptomatic of the whole industry. We can’t just critique Shantaram, he is just one of the many. We have to question a system that continues to make works like Shantaram’s possible.”

In April 2018, The New York Times published “Portraits of Dignity,” a photo series of young women kidnapped and later released by the Boko Haram after the government of Nigeria paid a ransom. The photographs were taken by Adam Ferguson with essays by its West Africa bureau chief Dionne Searcey. Searcy’s essay, “How We Photographed Ex-Captives of Boko Haram,” and the accompanying photographs—all 83 images of the girls shot in a single day—is a master class in how to reproduce colonial tropes and reduce the historical events that birthed the Boko Haram to a story about access. The portraits were designed to look like the 1974 portrait of Adetutu “Tutu” Ademiluyi by Ben Enwonwu.

Why did the writer-photographer duo think that this was necessary? Kathryn Mathers, writing in Africa Is A Country, says, “It is, though, astonishing that The New York Times would juxtapose such a collection of images with the story of a journalist’s tough road to capture them. It is quite literally a ludicrous juxtaposition between the extreme trauma and violence all of the photographs’ subjects have experienced and the pathetic struggles of an American writer in search of a particular image.”

I spoke to Maheder Haileselassie, Ethiopian photographer and founder of the Center for Photography in Ethiopia, soon after I started researching The African Portraits. For Haileselassie, what Shantaram set out to do—documenting racism against Africans—was not the problem. However, for her, “the claim is extremely different from what he did in the end.” She did not find the description of the work in itself problematic but what he ended up producing. “His gaze is problematic, not very different from the colonialist, orientalist gaze.” Haileselassie said, “That colonialist gaze is not just confined to images produced during the height of colonialism, where it was often common for the Africans or other colonial subjects especially women to be staged and posed naked. Seeing these images you immediately know that this is not their culture.” What she noticed was “he was following the same aesthetics, posing the person for the fascination of the viewer.”

As we came to the end of our conversation, I told Haileselassie that [Image] 23 was an African-American woman. Her first response was, “Wow, yeah!” For her, such a violation would make the whole body of work invalid because the photographer started with the notion of Africans in India and racism. There is no reason or explanation as to why this photograph is included except to fascinate a certain kind of western audience. When I asked her why such works continue to be circulated without critical intervention, she responded that “there is a gap in the world of photography. There are still funders funding this kind of problematic work. This is not just Shantaram but there are many more photographers who continue to produce such work. Despite many African photographers and many others in the industry who continue to complain about these kinds of images and practices, you continue to see these images being accepted by really “renowned” organizations. This tells me that there is still a viewer, there is still interest in images like these, and there is an audience for them. That is the reason why these images keep coming out. There is still a demand and a consuming audience that doesn’t see any problem with these kinds of work.”

Shantaram’s work is symptomatic of a culture, system, and people that enable toxic violent practices in photography globally. In case of India, however, many of these practices cannot be raised, argued, or discussed without the questions of caste, class, access, and privilege. A culture that elevates the storyteller above the stories, uses the banality of bearing witness as an excuse to produce extractive work, and has a remarkable tendency to conform and remain silent is one that needs to be challenged and torn down.

Postscript: In the course of writing this essay, four of the persons who agreed to speak on the record withdrew after exhaustive interviews. Their fear and silence is telling.

Editor’s Note: Publishing work about vulnerable and stigmatised people involves substantial choices made by authors and editors that sculpt its ideas and language beyond the first draft. In crafting this piece we have, as always, paid special attention to human subjects protocols that disallow any work from risking the identities and lives of those who speak their truth to the author. For the purpose of a piece of work, peoples’ lives cannot be reproduced onto paper without offering them a shield of protection under conditions of anonymity. At The Polis Project, we produce research and journalistic work that is ethical and held to the highest standards. It is because of these ethics that we have hidden the identities of those who collaborated with this project and did not want their names displayed.

We have used the blurred image of Alexis Ward with her consent and approval. The only reason for using images, blurred or pixellated, is for the purpose of instruction and illustration of the ideas and core concepts that the piece develops, which we think are important so that artists and photographers can use this critique to dwell more on their motivations in undertaking certain artistic projects and also to think more about their responsibilities to the subjects of their work. We see knowledge-building as a collaborative, democratic, and non-elite exercise. Therefore, we encourage our audience to write to us with their concerns and comments that our team always takes under advisement.