The terror of an anti-terror law in India: A short story of the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act

“People I used to call friends and had long discussions with now change their path when they see me coming,” Safoora Zargar told us as her son called her out.

At the time of her arrest, Zargar was over three months pregnant. However, she said it was the aftermath that changed her life. “It feels like you are guilty until you are proven innocent. So, for me, fighting this case and going through this trial is about the same. It is because we have already been stamped as terrorists.”

Zargar’s case at the time created an uproar mostly because she was pregnant, but also because there was no concrete evidence against her or any of the other 18 who were arrested at the same time.

On 6 March 2020, the Delhi Police’s Crime Branch invoked against them various sections of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) and of the Indian Penal Code and registered the case under the infamous First Information Report (FIR) No. 59.

The Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act is one of India’s anti-terror laws in effect since 1967. Originally conceived to stop “unlawful activities,” it has de facto become a tool to curb dissent. Considered to be one of India’s harshest anti-terror laws, UAPA allows authorities to arbitrarily designate someone as a “terrorist” and detain them without producing any incriminating evidence.

Many critics believe that the law is being misused to curb the voices of dissenters. One of them is 30-year-old Zargar, an activist and scholar, who was slapped with UAPA and jailed for three months as she was charged with terrorism and murder under the Act.

Zargar was pursuing her MPhil from Jamia Millia Islamia when she was arrested on 10 April 2020 in connection with the anti-Muslim pogrom that took place in New Delhi from 23 to 25 February 2020.

Although the UAPA has been in force since 1967, the Parliament inserted a chapter dedicated to punishing terrorist activities only in 2004 by way of the UAPA Amendment Act, 2004.

The law was passed under the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government, which came to power in 2004, and became increasingly more draconian through substantial amendments in 2004, 2008 and 2013.

Prior to UAPA, terrorist activities were primarily dealt with under the now repealed Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act, 1987 (TADA) and Prevention of Terrorism Act, 2002 (POTA).

Both the laws were called draconian during their time. While they were in use, various civil society reports criticized the constitutional validity of TADA and POTA.

TADA was instituted in the mid-1980s when separatist movements gained momentum in India, especially in the Punjab. The law gave wide powers to law enforcement agencies for dealing with national terrorist and socially disruptive activities. Under TADA, children as young as 12 were arrested. In Assam, for example, Paresh Kalita was charged under TADA in 1991 and put in jail for “inciting trouble” against the State.

POTA, on the other hand, was in force for almost three years from 2001 to 2004. Under this law, people could be arrested on suspicion and detained without charge or trial for six months. In February 2003, 28 Dalit and Adivasi agricultural workers in Uttar Pradesh were arrested under POTA for allegedly being Naxalites. Some of those arrested were later shot in an encounter killing.

The same year, during a discussion on POTA, activist Gautam Navlakha noted: “A law is bad in itself when it overturns all notions of natural justice on its head and allows the executive to apply the law at its subjective discretion.” Navlakha outlined how the preventive nature of POTA allowed for the law to be misused. The activist himself has later been slapped with UAPA in the Bhima Koregaon conspiracy case and, at the time of writing, is under house arrest.

A report titled “People’s Tribunal on the Prevention of Terrorist Act (POTA) and Other Security Legislations” was released on 16 July 2004, based on depositions made before the Tribunal by the victims of POTA from ten states in India. It included expert depositions by lawyers and activists revealing that these security legislations grant sweeping powers to authorities and have led to misuse of powers and major human rights violations.

Former judge Anjana Prakash wrote that UAPA was passed as provisions of POTA “were being misused. […] Since the government was firm in its resolve to combat terrorism and in view of commitments given in the UN in terms of Resolution 1373, it considered it necessary to criminalise various facets of terrorism by appropriate amendments in the UAPA.”

After the 9/11 attacks, the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 1373 on 28 September 2001, which obliges all member states to implement more effective counter-terrorism measures at the national level and to increase international cooperation in the struggle against terrorism.

These requests were reflected in the changes made to UAPA, which included legislating on funding terrorism and the seizing and freezing of terrorist organizations’ assets.

The UAPA was further revised in the wake of the terrorist attack in Mumbai on 26 November 2008 that killed 166 people. The same year, the National Investigation Agency (NIA) Act was passed, establishing a separate cadre of the police force to tackle terrorist crimes. The NIA has wide powers and, unlike the Police, is directly under the control of the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) of the Government of India.

According to the NIA Act, 2008 states can request the central government to hand over the investigation to the NIA if the case includes offences listed in the schedule to the NIA Act.

The central government can also ask the NIA to take over the investigation of any scheduled offence anywhere across the country under Section 6(5) of the Act. This basically means that the Agency is empowered to replace the Police and deal with the investigation of terror-related crimes without permission from the states. Under a written proclamation from the Ministry of Home Affairs, this is intended to ensure effective and speedy trials in terror-related cases.

In a report published on 28 September 2022 titled UAPA: Criminalising Dissent and State Terror, the People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) discussed the alleged abuse of the legislation between 2009 and 2022 and demanded to repeal the law.

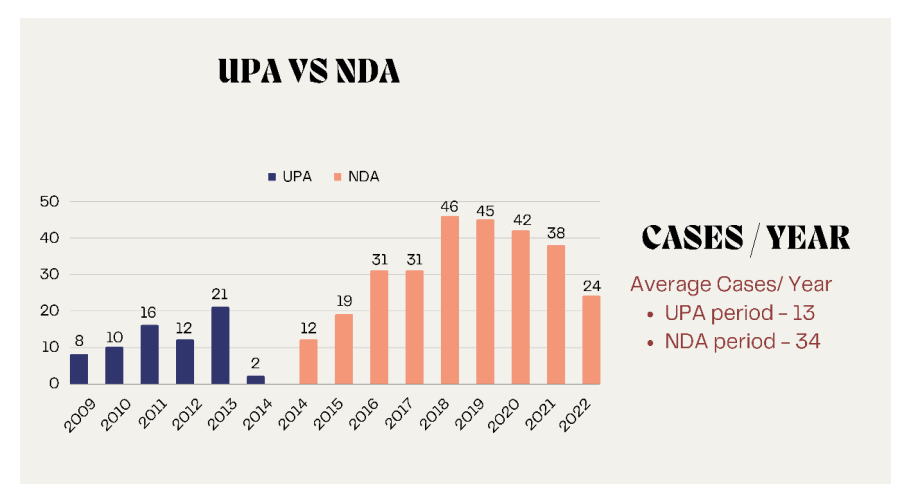

The report included data on the number of arrests as well as the conviction rates under UAPA in cases handled by the NIA both during Congress and Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) governments.

When Prime Minister Manmohan Singh was in power from May 2009 to May 2014, the NIA registered 69 UAPA cases; whereas there have been 288 UAPA cases during the tenure of current Prime Minister Narendra Modi from May 2014 to the present.

The average number of UAPA cases registered per year by the NIA during the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) alliance – a centre-left political alliance of political parties – is 13. In contrast, during the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) – a conservative political alliance led by the BJP – the average number of cases registered per year is 34.

Senior lawyer and PUCL general secretary V. Suresh told us in an interview that the “NIA data are of great concern and very clearly show how the agency is being used. UAPA is being weaponized and NIA is being used by the government for clampdown. Of course, it’s a weapon to put down activists.”

The PUCL report concluded that the “contrast in figures clearly shows that during the Modi era, there is an increasing tendency to use UAPA as the chosen legal weapon.”

Source: PUCL, UAPA: Criminalising Dissent and State Terror

On 24 July 2019, the BJP-led government passed the Unlawful Acts (Prevention) Amendment. According to the government, “the amendment to the UAPA Act will help the government and intelligence agencies to remain four steps ahead of terrorists and non-state actors.”

The amendment brought two distinct changes to the original text of the UAPA Bill: it gives the NIA complete autonomy to conduct its operation in any state of the country without informing the state or local authorities; and it gives the central government unrestricted power to add or remove names of individuals from terrorist watchlists without reasonable justification.

Critics of this controversial amendment have pointed out that the provisions of this statute violate the integrity of the federal structure of India.

Former Indian Police Service Officer and politician Swaran Ram Darapuri told us that this law is draconian in nature and a threat to law and order. “The law is being used on social activists, human rights activists and particularly on [political] opponents. This is a black law,” he told us.

Former judge Anjana Prakash in her article noted that the statute goes against the Indian Constitution and that the UAPA specifically contradicts the underlying principles contained in Article 21 and Article 14, which respectively deal with protection of life and personal liberty and equality before the law irrespective of religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth.

In contradiction to these principles, clauses such as Section 35 (2) of the UAPA amendment give the government a free hand in designating any individual as a terrorist and detaining them for up to two years without judicial appeal.

Since its re-election in 2019, the BJP has claimed to have clamped down on terrorism and applauded the use of UAPA in the fight against terrorist activities.

However, the new amendments made bail difficult to secure since Courts assess the case only based on the chargesheet prepared by the NIA and the accused cannot provide any evidence in their defense.

Zargar, whose case is still ongoing, told us that the bail conditions have deeply impacted her life. “There are so many bail conditions that have limited my mobility and my prospects as a researcher. They have impacted both my work and my personal life.”

She told us that her life has come to a standstill. “I have to wait for the Court’s permission to even go and visit my hometown. This is in itself a punishment,” she added.

The activist is also banned from entering the Jamia Millia Islamia university premises after the administration issued a notice. “My future prospects are bleak due to all this,” she added.

Senior lawyer V. Suresh told us about the concerns of the opposition when the UAPA was passed. “The point that was raised in Parliament by most MPs [Members of Parliament] was that it gave too much unbridled, uncontrolled, unregulated, unmonitored power to the central agency with no judicial oversight. This is not an ordinary law, this is a special law, it has to be used only for special occasions, to put down terrorism.”

The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), the government agency responsible for collecting and analyzing crime data, recorded that 6,900 UAPA cases were reported between 2014 and 2020, an average of 985 cases per year with a peak of 1,226 cases in 2019.

The PUCL report, however, points out the lack of accuracy in the NCRB figures. Many trial court lawyers and activists from states like Chhattisgarh and Karnataka have pointed out to a large number of cases in their states in which scores of local persons have been arrested and kept in prison over long periods of time, which do not find reflection in the NCRB statistics.

Factchecker, India’s first dedicated fact checking initiative, in a report stated that the number of cases pending investigation is continuously rising at a yearly average of 14.38 percent. The cases pending investigation were 1,857 in 2014, rising by 37 percent to 2,549 in 2015 and to 4,021 in 2020.

The report Uncertain Justice: A Citizens Committee Report on the North East Delhi Violence 2020, released by a committee of former judges and bureaucrats, argued that UAPA has been used to create a larger conspiracy. It showed how UAPA was misused after the Delhi violence and how “patterns of larger use of the UAPA suggest its targeted application by the state.”

From 23 February to 25 February 2020, 53 people were killed and hundreds were injured and rendered homeless after a right-wing mob shielded by the Police stirred violence in north east Delhi. Muslim houses, markets and institutions were attacked and burnt down. Eyewitnesses recalled that people were asked their names and, while Hindus were let go, Muslims were assaulted.

Notably, after three days of pogrom, the mob was let go unpunished while the Delhi Police registered a case for conspiracy in the FIR 59 against 18 people – mostly Muslims – who are activists (including Safoora Zargar), student leaders (such as Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam) and local community organizers.

More than 750 FIRs were lodged in the riot cases till date and included offences such as giving instigating speeches, creating religious hatred, looting, arson, destroying public and private property, causing injury and murder among others.

However, FIR 59 is the most crucial as the Delhi Police has alleged that the riot was pre-planned and that the protest against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) allegedly created a communally-charged atmosphere that led to the clashes in February.

At the time of writing, most of the accused in the FIR 59 either remain in jail or are out on bail awaiting trial. The report by former bureaucrats and judges pointed out that this ongoing legal process has in many ways become the punishment. “The law enables prolonged pre-trial custody of individuals through drawn-out investigation and exceedingly limited grounds to secure bail. UAPA accused are very often acquitted in their trials due to insufficient evidence, yet, forced to remain in custody, often for years. This ensures the legal process itself becomes punishment.”

The authors of the report also reiterated the urgent need for a comprehensive review of the UAPA.

While for activists like Safoora Zargar, UAPA has caused unimaginable loss and trauma, the law and its ramifications have a serious and lasting impact on Indian civil society and freedom of expression as they target with deliberation and impunity political opponents and voices of dissent.